In the middle of July the sons of illustrator and comic strip artist Alden Spurr McWilliams (1917-1993) made a significant gift of 33 original strips and Sunday paper boards to the Norman Rockwell Museum. The previous year, one of the sons and his wife visited the museum and talked with curator Joyce Schiller about Al McWilliams, his career, and the care and preservation of the work that remained.

McWilliams, also known as “Mac,” trained at the New York School of Fine and Applied Arts and began his career in 1938 creating drawn interior story illustrations for pulp magazines. The following year McWilliams began to draw comic book art for various comic book producers (Dell, Centaur Comics, Quality, and Funnies Inc.) working on Captain Frank Hawks, Speed Bolton, Flash Gordon, and Stratosphere Jim.

After serving in the U. S. Army during WWII and receiving the Bronze Star and the French Croix de Guerre, McWilliams returned to Connecticut, married, and continued his illustration and comics career. In the 1950s and 60s, Mac drew several popular syndicated newspaper comic strips. The first, a science fiction comic strip Twin Earths, was originally written by Oskar Lebeck and ran in daily and Sunday newspapers from 1952 through the early 1960s. When Lebeck retired in 1957, McWilliams took over the scripting of the stories in addition to drawing them.

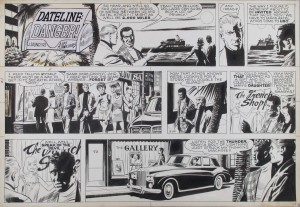

In the 1960s McWilliams and writer John Saunders created and produced a new syndicated comic strip, Dateline: Danger! about two intelligence agents, one black, Danny Raven, and one white, Troy, a.k.a. Theodore Randolph Oscar Young, who work undercover as reporters for a news organization. They consulted Allen Saunders, John’s father, who was the writer of Steve Roper and Mike Nomad, Mary Worth, and Kerry Drake comic strips for advice on their strip.

Like the dramatic TV show I Spy and its inspiration, Dateline: Danger! was the first in its medium to have a lead character who was also an African American. McWilliams’ visualization of the African American characters was artfully done so that there was no inference of creating a modern black-face character, but rather these characters were realized as ‘straight’ comic strip drawings of black people. Prior to the creation of Dateline: Danger! McWilliams had drawn the comic book work version of I Spy for Western Printing. His experience drawing the Bill Cosby character in comic strip form gave the artist a leg-up on the assignment.

The comic strip title block always appeared as though it was being printed on the paper coming off of a telex network teleprinter. Telex was a network of teleprinters that sent and received text-based messages printed line by line on a paper roll. The paper message could be torn from the roll and taken away. The forerunner of modern faxing, email, and texting, the telex network routed messages by telex address. This equipment was commonly seen in television and newspaper newsrooms making it a readily understandable icon of its time.

Dateline: Danger! and I Spy we part of the larger media attempt to address previous racial stereotypes and to offer a broader range of characterizations regardless of the color of a character’s skin. The strip ran from 1968 through 1974.

The McWilliams family donation of Twin Earths and Dateline: Danger! strips to the Norman Rockwell Museum collections not only broadens our base of work from the field of American comic strips, it gives the museum examples of two seminal strips from their earliest days. The boards of Twin Earths strips showcase Al McWilliams’ imaginative view of Terra’s architecture, aero-technology, and life style issues such as clothing and gender roles. While the importance of Al McWilliams’ visualization of integrated contemporary life in the America seen in Dateline: Danger! strips cannot be over-acknowledged. In both of these comic strips Alden Spurr McWilliams affirmed the technological potential we are, even now, seeing come to fruition as well as the necessary future societal shifts we are inhabiting.

Dr. Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, Norman Rockwell Museum