Edward Hopper (1882-1967). (“At the Theater”), (c. 1916-1922). Brush and ink and wash, opaque watercolor and fabricated chalk on paper. Sheet: 18 1/2 x 14 7/8″. (47 x 37.8 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Josephine N. Hopper Bequest 70.1440. ©Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, licensed by Whitney Museum of American Art. Digital Image © Whitney Museum of American Art.

Rockwellian. Hopperesque. You know you have made it when your name becomes an adjective.

This past December, artwork by Norman Rockwell (1894-1978) and Edward Hopper (1882-1967) set the all-time sales records for American paintings at auction, confirming the enduring popularity of these two artists from the twentieth century.

Although highly regarded for their painting and storytelling skills, most people are unaware that both Hopper and Rockwell started their careers in a similar fashion, before traveling on a very different course.

As a boy growing up in Nyack, New York, Edward Hopper drew frequently, and by the age of ten, he began signing and dating his work, indicating a seriousness of intent. Though they supported his artistic ambitions and retained his early work, his parents advised him to study commercial illustration rather than fine art, believing this to be his best hope of earning a living in the field.

In the fall of 1899, when Hopper was 17, he began formal art training at the New York School of Illustrating founded by Charles Hope Provost. “To many students of an extremely artistic temperament all commercial work is distasteful,” he wrote—an admonition that could almost have been directed at Hopper himself. A year later, Hopper moved on to the New York School of Art, a more prestigious institution on West 57th Street founded by American impressionist William Merritt Chase. There, he studied illustration for another year, this time with Arthur Ignatius Keller, whose classes focused on drawing from the figure and costumed model as a means of strengthening technical and narrative skills. The school also offered instruction in fine art, which Hopper was determined to pursue.

In 1908, at the age of 14, Norman Rockwell also enrolled in art classes at The New York School of Art. Two years later, in 1910, he left high school to study art at The National Academy of Design. He soon transferred to The Art Students League, where he studied with Thomas Fogarty and George Bridgman. Fogarty’s instruction in illustration prepared Rockwell for his first commercial commissions. From Bridgman, Rockwell learned the technical skills on which he relied throughout his long career. Brought up on the stories of Charles Dickens, and the art of such Golden Age illustrators as Howard Pyle, Rockwell strove to make it as a commercial artist.

Just a few years later, the 1913 New York Armory Show introduced Europe’s avant-garde artists to America in the biggest art show ever, standing the art world on its head as 90,000 visitors encountered modern art for the first time. Hopper’s 1911 painting, “Sailing” made it into that show, a beacon for the artist who had been working as an illustrator for 12 years but struggled to break free of the commercial constraints of a profession he did not enjoy. In 1916 a young Rockwell would land his first cover commission for The Saturday Evening Post, the start of a long and successful creative partnership with the publication.

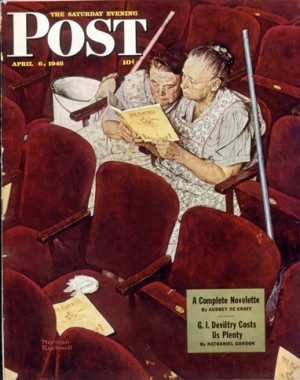

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), “Charwomen in Theater,” 1946. Cover illustration for “The Saturday Evening Post,” April 6, 1946. Norman Rockwell Museum Digital Collections. ©SEPS: Curtis Publishing, Indianapolis, IN. Featured in the Norman Rockwell Museum exhibition, “Norman Rockwell’s 323 ‘Saturday Evening Post’ Covers.”

In her essay for the exhibition catalogue, The Unknown Hopper: Edward Hopper as Illustrator (2014), noted Hopper scholar Gail Levin points out that the artist “insisted that he had never aspired as high as The Saturday Evening Post, the popular magazine for which

Norman Rockwell continued his successful career as an artist and illustrator through the next six decades. He was quoted as saying that “the kind of thing I like to do, I know it isn’t the highest form of art… I love to tell stories in pictures. The story is the first thing and the last thing. That isn’t what a fine art man goes for, but I go for it and I just love to do it that way.”

Hopper found a different way to tell stories that connected with the American public, yet many of the motifs and compositional devices that appear in the artist’s later paintings are also seen in his etchings and illustrations. He is quoted as saying that, “In every artist’s development the germ of the later work is always found in the earlier… the nucleus around which the artist’s intellect builds his work is himself; the central ego, personality, or whatever it may be called, and this changes little from birth to death. What he was once, he always is, with slight modification. Changing fashions in methods or subject matter alter him little or not at all.”

Artist… storyteller… illustrator… words used to describe two of of America’s best-known painters of the twentieth century, over the course of their remarkably similar yet different careers.

Related Links:

The Unknown Hopper: Edward Hopper as Illustrator

Norman Rockwell’s 323 “Saturday Evening Post” Covers

Buy Hopper and Rockwell product in the Norman Rockwell Museum Store