New York Cartoons Reviews Mad Magazine Exhibition

Stockbridge, MA – June 25, 2024– MAD Magazine Finally Gets the Curtain Call it Deserves. Growing up, the Usual Gang of Idiots were the demigods in my comedic Pantheon; The show at the Norman Rockwell Museum is a perfectly curated collection of seven decades of their misdeeds.

The day I became an Idiot was the highlight of my professional cartooning career. For all the prestige and grist of finally getting into the New Yorker, nothing will ever top the thrill (or lump of vomit in my throat) of getting my first cartoon in MAD Magazine, decades after laying my grubby little mitts on my first copy. To give you a sense of the contrast in fervor: As a kid I would blow my allowance buying MAD, but I would pilfer copies of the New Yorker from my dentist’s waiting room. (I blame the bad influence of MAD.)

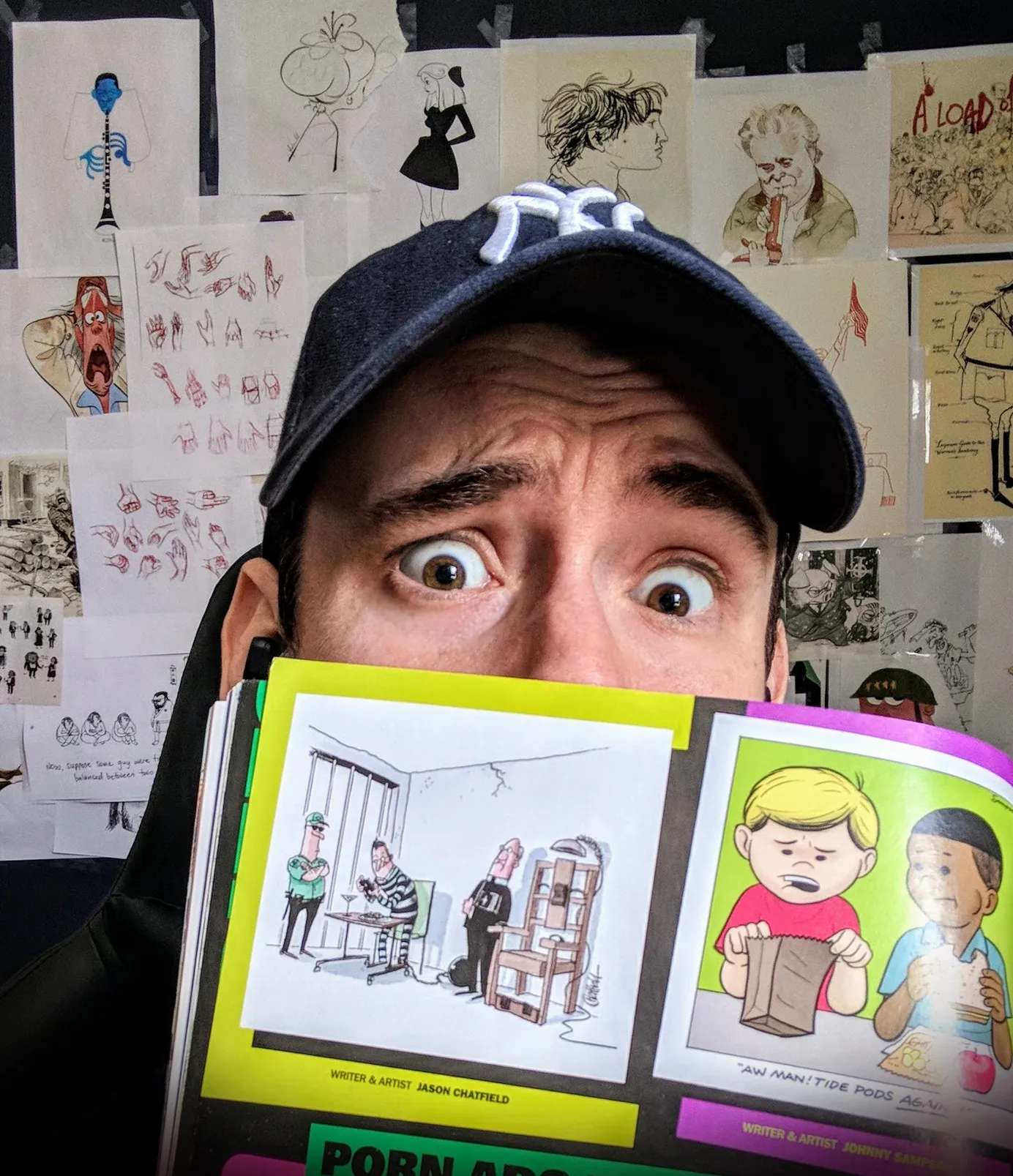

I’m writing this on the train back to New York after a whirlwind trip to be a guest speaker at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Massachusetts. As part of the exhibition “What, Me Worry? The Art and Humor of Mad Magazine” I sat down with my friend and fellow MAD alum, Emily Flake for a long talk about MAD’s influence on us as young cartoonists.

An odd mix of thoughts and feelings are swirling around my cavernous skull, including the sad realization that this will probably be the last exhibition of its kind I’ll ever see.

This may even be the last thing I get to write about MAD. The show was certainly a celebration of the incredible, singular achievement of what the Usual Gang of Idiots created over 7 decades, but it also felt like one final curtain call. The magazine has been running repeats of old material (with the exception of new covers and fold-ins) for the past handful of years. Nobody is sure for how much longer that will continue.

My journey from first discovering MAD to being a regular contributor is a long and complicated one, but I’m forever grateful for being part of the legacy (even if maybe I did arrive at the party just as they were sweeping up the cups.) Such is the peril of making your career goals at the age of 10; by the time you finally get close enough to touch them they’ve been locked behind glass in a museum.

In this post, I’ll share my thoughts on the new exhibition (which is incredible), as well as the story of my personal connection with MAD over the years. Needless to say, Alfred E Neuman has done more* to, and for me than any other influence in my life. *(irreversible brain damage)

I recommend you make the trip to see the exhibition if you have the opportunity before it closes in October. You won’t see anything like it again.

Over the past decade or so, I’ve been lucky to see all kinds of MAD shows and special events that have been a celebration of one aspect of the magazine, or its influence on the culture at large. I even got to enjoy being part of one of the final times the the majority of the Usual Gang were together1 in one place, back in Vegas in 2012 to celebrate the magazine’s 60th anniversary at the Reuben Awards. (The MAD-Men themed after-party was one for the ages.)

The distinction of this exhibition is that curators, Steve Brodner and Stephanie Plunkett had longtime MAD artist & Art Director Sam Viviano as lead advisor for the exhibition, so there were a lot of artists and writers featured who might not have ordinarily made the cut in a MAD retrospective. It made it all the more special to see the work of friends and idiots like Ray Alma, Teresa Burns Parkhurst, Emily Flake, Rick Tulka and Hermann Mejia among others.

Emily and I arrived to a very warm reception on Friday — the security guard nearly threw us out when he saw we weren’t wearing admission stickers. But then we assured him we were MAD artists (so he threw us out and locked the doors.)

The museum staff were amazing, so were the audience in attendance. The talk went for about 90 minutes. We covered a lot of territory— streaming the whole thing over zoom for those who couldn’t make the trip, fielding additional questions during the interactive Q&A portion.

We shared our work from our time at MAD, spoke about our early years reading the magazine, the art, the writing, the influence the tone had on our comedic senses, stylistic influences and lessons from the structures of satire, how the MAD team took humor seriously, and of course the influence Nick Meglin had on pretty much everything I loved about MAD. I may do a totally separate post on Nick. He’s a special part of the MAD history and I don’t know if I can articulate it much better than Tom Richmond already did on his blog.

One of my favourite memories is when Nick and I were stuck in the Memphis airport during a freak lightning storm and they couldn’t get our luggage off the plane for hours. Everyone around us was freaking out, but Nick just sat quietly, took out his sketchbook and pen, and began drawing the people around him.

The one book I re-read every year without fail is “Drawing From Within” by Nick, and his daughter Diane Meglin. It’s the first book I recommend to any artist who asks what they should read to learn about drawing. (The second one is “The Art of Humorous Illustration” which also happens to be by Nick. There’s a pattern here.

Something that occurred to Emily and I as the conversation kicked past the hour mark was that we’d both individually had one very key advocate involved along our MAD journey, and that was the above-mentioned Sam Viviano. If nobody had read the ads for this talk, they could easily have assumed it was entitled “Sam Viviano won’t you please be my papa?

Sam not only helped curate this exhibition, but his editorial and directorial f ingerprints were the reason the magazine looked and read as good as it did in its f inal decades. His eye for humorous illustration is well-honed, and his sense of visual balance is rivaled only by his patience with artists! I can’t imagine having to herd cats for a living, but somehow he managed to get cartoonists to turn their work in on deadline every issue.

On top of all of that, he’d give out-of-towner nobodies like me a tour of the offices when they showed up on his doorstep, he would encourage young artists of all stripes, teaching at SVA for years, and is the major reason I’m even an American resident!

…But I’ll get to that later. This isn’t Sam Viviano’s resumé. (Although, that might be more interesting to read.)

Some people remember where they were when man Trst walked on the moon. Others can recall where they were when they Trst heard the Beatles. Me, I can tell you exactly where I was the Trst time I ever saw a copy of MAD Magazine.” ~ John Ficarra, MAD Editor.

To this, I can relate. I grew up in the suburbs of Perth, Western Australia— The most isolated capital city on Earth. The Southwest tip of Australia is as far from New York as you can get. If you drill a hole from Manhattan through the core of the planet, you come out in the Indian Ocean, just west of my family home. As a kid, New York was as foreign to me as the moon.

My high school best friend, Ben (above left) would invite me around to his place in Sorrento to hang out on weekends. His Dad —a Texan expat— had mercifully imported moldy boxes of classic dog-eared issues of US MAD from the ‘70s and ‘80s. We pored over them for days at a time. It was like a portal to another dimension. We couldn’t believe there was something like this in the world, much less that anyone would let them publish this absurd symphony of hot garbage. It was adults behaving like our peurile teenage peers —in print! We couldn’t get enough of it.

I would study the Mort Drucker movie and TV parodies, Jaffee’s fold-ins, Sergio’s pantomime marginalia, and Don Martin’s onomatopoeia, scanning Yiddish-laden gags with esoteric references I couldn’t possibly understand. There wasn’t an inch of the magazine that wasn’t covered in jokes and illustrations. The chicken fat2 f illed every gap on the page. Over time, we built a corpus of idiotic comic reflexes that would invariably deem us unemployable. Alfred E. Neuman imbued in us a deeply entrenched skepticism of anything that took itself too seriously. It was infectious.

It was no surprise that Ben went on to become a (much funnier) comedian. We toured as a musical comic duo called “ManFace” for a bunch of years before I lost grip on his coattails. We both still perform comedy on different continents, but the formative effect that MAD had on us, and generations of comedy writers is incalculable.

What, me Sorry? When I was 13, I remember my mum being furious when I returned home from the corner store with an armful of MAD comics and lollies3. There wasn’t a cent remaining from the allowance she’d given me twenty minutes prior. I had no remorse. She told me I had to get a job as a paperboy to learn the responsibility of saving money. Every week, the moment my paperboy pay hit my sweaty little palm I jumped on my bike and rode to that same corner store, leaving with an armful of MAD (and Spider-Man comics.)

I never went to art school— studying the work of the idiots was my art school. After graduation, while my fellow aspiring artists went off to college and studied Renoir and DaVinci, I stayed home and studied Drucker, Davis, Jaffee, Aragonés, and the litany of clowns (dis)gracing the pages of MAD. I got a job at a print shop by day and drew cartoons by night, trying to replicate the styles of the Idiots. They made it look easy, but as I quickly came to discover, comics and humorous illustration are some of the most difficult art forms to do well. (Let alone truly great satire.)

They had so many impressive pieces from way back when MAD was still a comic book in the early 1950’s. The original letters between Rockwell and MAD about illustrating a cover are there, too. (It fell through at the last minute, but it was a fun idea.) The MAD comic book converted to magazine format as of issue No. 24, in 1955. The move had removed MAD from the strictures of the Comics Code Authority. Bill Gaines said in 1992 that MAD “was not changed [into a magazine] to avoid the Code” but “as a result of this [change of format] it did avoid the Code.

Richard William’s pitch-perfect spoof of Rockwell’s famous self-portrait for the book MAD ART is hung right next to the Norman Rockwell original. As you might imagine, getting to see the original paintings up close was mind-collapsing.

The Mort Drucker Room. It was surprising to see that one entire room of the exhibition was dedicated to just one artist, but there’s no doubt he was a singular talent. Mort Drucker had an ability to capture a likeness like no other artist— and from any angle.

Studying his work is both mesmerizing and madenning. You can’t simply reverse engineer his thought process; everything is just so deeply entrenched in his muscle memory. I believe he and Jack Davis might just have been two of the best humorous artists of their generation.

I first had the surprise privilege of meeting Mort when I was 21. It was my first trip to New York, where Adrian Sinnott had invited me to the Bunny Bash; an annual summer cartoon party at a castle on Long Island. Bunny Hoest was the generous host, and everyone who was anyone in the cartooning business could show up. I was lucky to get an invite!

That day I got to meet some of my favourite MAD artists, but also fellow cartoonists who would later go on to become some of my closest friends. (Except Ed Steckley. He still needs to learn how to draw.)

A few years later when I was back in New York —another schlep from Australia— I got to sit with Mort for the afternoon in his studio while he worked. I watched as he pencilled in knuckles and joints to hands connecting to wrists with this bizarre aesthetic perfection. It was still caricature, but it felt like fine art. This was the guy whose work I had painstakingly studied and tried to emulate from before I even had pimples.

He would gently talk about the ability to make hands as expressive as a human face; to tell a story through pose and gesture without writing a word. He was as obsessed with the miracles of human anatomy as DaVinci, but with a much better accent.

By the time we finished up, my brain had been rewired. One hour with Mort was like 10 years of art school. On my way out, he grabbed a MAD cover and signed it to me, not knowing what a big Spider-man fan I was. It still hangs behind glass in my studio to this day.

The room at the show has a staggering volume of original art from iconic movie and TV parodies that Mort had done over the years. So iconic had they become that on “The Tonight Show” in 1985, Michael J. Fox told Johnny Carson that he knew he had made it in show business “when Mort Drucker drew my head.” The director Joe Dante wrote that “There are few thrills in life quite like seeing your own movie parodied in the pages of MAD.”

I have some original versions of Mort’s work from when he was working on the Bob Hope comics. The exhibition also shows original art from a strip he did around 84-86 called Benchley, about the Ronald Reagan Whitehouse. It showed his ability to caricature famous faces at different angles and expressions with deft line economy, landing funny gags with great pacing. It’s truly one of the rare examples of a comic strip using caricature masterfully.

Mort died in the early days of the pandemic. We never got to say goodbye, or have a funeral or memorial. We were locked down in a horizonless tsunami of bad news. I like to think this room is perhaps the fitting memorial he never got. You can read more about my thoughts on Mort here.

Beyond Mort, there are of course the cavalcade of geniuses who wrote and drew the unthinkably stupid collection of dross that ceaselessly disgraced subscribers’ mailboxes every month.

There are the creative legends who created entirely new words of onomatopoeia, like Don Martin. Or Jack Davis, who drew stunning artwork for the silliest of jokes. Or the famous back page Fold-In, one of many of the ingenious innovations from the snappy mind of Al Jaffee.

Jaffee holds the Guinness World Record for the longest career in comics. When we were all gathered at Sardi’s for the presentation of the record on Al’s Birthday, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio declared March 13 Al Jaffee Day.

Al’s incredible hand-painted works of art get a nice showing in the gallery, but staff discourage people from cracking the glass open to fold them in.We had to bid farewell to Al last year at the ripe old age of 102.

Next to Al is another Usual Gang-member on display who, when he showed up at MAD’s in the early 1960s as a Mexican immigrant, slept in the offices until he could find a place of his own. He didn’t really speak much English, but he had a work ethic and hustle that rivalled anyone in the business.

I am of course talking about the legendary Sergio Aragonés. They often say “Never meet your heroes…” but they rarely mention the second part: “…unless your hero is Sergio Aragonés.”

By Jason Chatfield