Norman Rockwell: Covering the Post

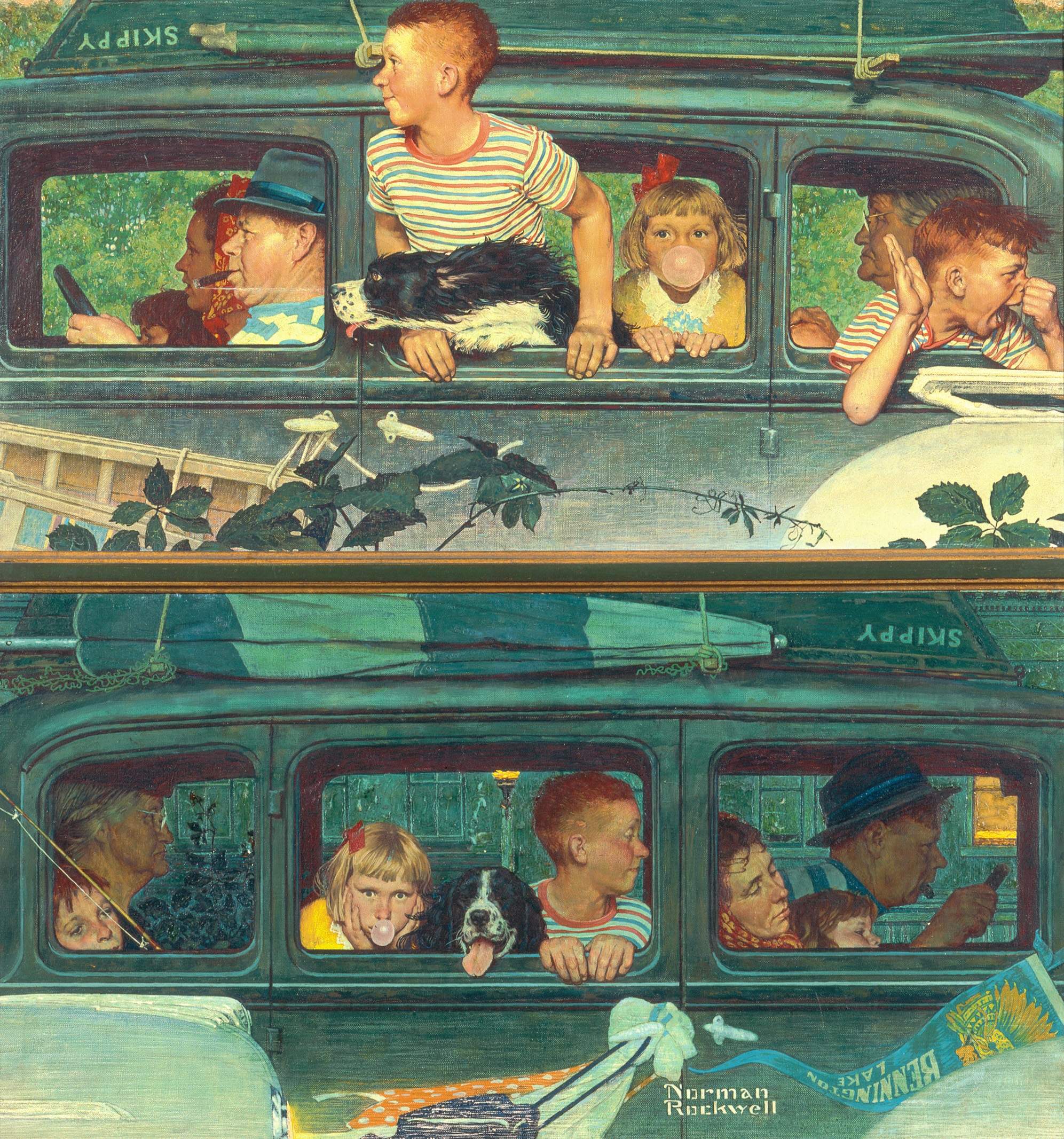

Like most illustrators, Norman Rockwell worked within the realm of aesthetics, commerce, and technology. An astute visual storyteller and a masterful painter with a distinct, personal message to convey, Rockwell constructed fictional realities that offered a compelling picture of the life that many Americans aspired to. Anxiously awaited by an enthusiastic public, his seamless narratives assured audience engagement with the publications that commissioned his art- particularly The Saturday Evening Post, which was the primary publisher of his work for forty-seven years, from 1916-1963. What came between the first spark of an idea and a published Rockwell image was far more than readers would have ever imagined.

“I love to tell stories in pictures,” Rockwell said. “For me, the story is the first thing and the last thing.” He considered the Post to be the “greatest show window in America for an illustrator.” Conceptualization was central for the artist, who called the history of European art into play and employed classical painting methodology to weave contemporary tales inspired by everyday people and places. His richly detailed, large scale canvases offered far more than was necessary even by the standards of his profession, and each began with a single idea. Admittedly “hard to come by,” strong picture concepts were the essential underpinnings of Rockwell’s art.

Rockwell’s positive outlook on humanity was a hallmark of his work. From the antics of children, a favored theme of his youth, to the nuanced reflections on human nature that he preferred as a mature artist, each scenario was inspired by his personal observations of the world around him. In 1943, a Time reporter aptly noted that Rockwell “constantly achieves that compromise between a love of realism and the tendency to idealize, which is one of the most deeply ingrained characteristics of the American people.”

Illustration and the American Magazine

In the first half of the twentieth century, general-interest magazines like The Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s—and popular women’s magazines such as Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, and McCall’s—built vast, loyal followings. Emerging from a long period of political and economic transformation following the Great Depression and World War II, Americans began to re-imagine themselves and the new lives they hoped to lead. Production, finely tuned by wartime necessity, enabled a booming peacetime economy with a plethora of new products and modern, time-saving conveniences.

Directly linked to commerce, richly illustrated magazines featured aspirational images depicting idealized standards of living. Top publications boasted two to nine million subscribers in the 1940s and 1950s making Rockwell and other popular illustrators prominent taste-makers—their art played a crucial role in affecting cultural beliefs and desires and in envisioning the American dream.

In observing the art on view, it’s important to note that during Rockwell’s time American periodicals were marketed to a largely white demographic. In 1940, the population in the United States was 89.8 percent white and 9.8 percent black, with other races and ethnicities falling within the category of “other.” Until the Civil Rights Movement, people of color were almost completely invisible on the pages of American magazines. Prevailing attitudes toward race and damaging representations of African Americans during the Jim Crow era and beyond were reinforced in mass-circulated periodicals like the Post, Rockwell’s primary publisher from 1916 to 1963, which portrayed people of color in distinctly subservient roles.

Art for Everyone

Known for idealized realism inspired by everyday situations for the covers of The Saturday Evening Post, Norman Rockwell created artworks that served as an introduction to fine art for the masses. Though he worked as a commercial illustrator, he employed classical techniques to give two-dimensional pictures the illusion of space and depth.

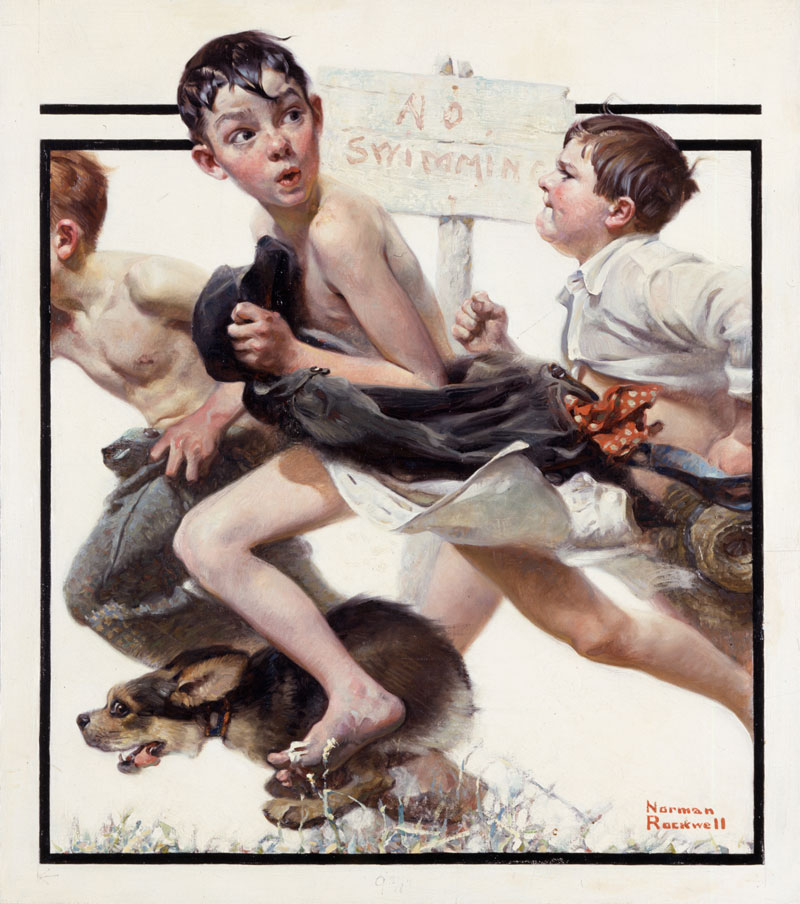

In his early Post covers, Rockwell’s artwork floated on a white ground to suit the magazine’s graphic identity. He could not use landscapes, architecture, or open doors to create the illusion of three-dimensionality. Instead, he relied on the overlapping of shapes, masterful shading, and foreshortening -the compression of objects to make them appear to recede into the distance. In No Swimming, Welcome to Elmville, and Boy and Girl Gazing at the Moon, the artist used eye-catching signs and hovering moon to create surface planes. Rockwell gave figures volume by adding cast light and shadow, a technique termed chiaroscuro. Shadows cast by figures give us the sense that they are standing on real ground.

The influence of seventeenth century Dutch painters was distinct in Rockwell’s later covers. Art Critic is reminiscent of a Dutch genre scene, but in this case, we see an art student leaning in to more closely observe a museum masterpiece. Rockwell’s narrative is set in a room filled with architectural elements, a tiled floor, and paintings⸺a nod to centuries-old Dutch portraiture and group portraits which were popular at the time. In Marriage License, Rockwell included an open window through which a distant view is seen. This is an example of doorkijkje, or “see-through,” a device used by Dutch artists to achieve pictorial depth.

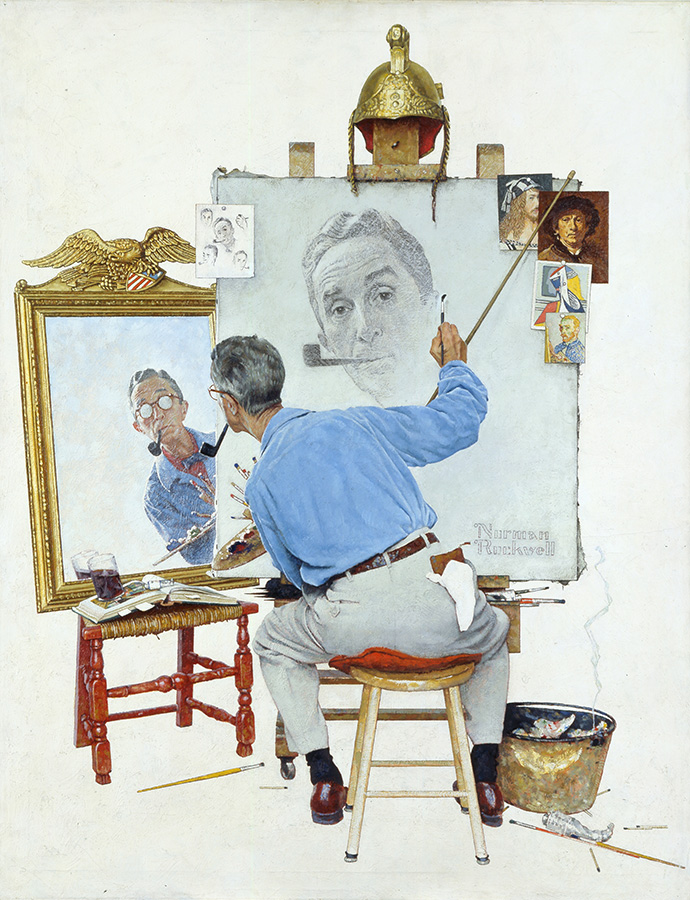

Throughout the course of art history, self-portraits have been prevalent in every major art movement, from the Italian Renaissance to the Contemporary period. Rockwell illustrates this in Triple-Self Portrait by including the recognizable self-portraits of Albrecht Durer, a fifteenth century Northern Renaissance artist; Rembrandt van Rijn, a seventeenth century Dutch master; Vincent van Gogh, a nineteenth century Impressionist; and Pablo Picasso, a twentieth century Cubist, in his composition. These images are not necessarily realistic reflections of the artists, but rather exercises in self-exploration. Each had the choice to reveal the inner self or bare only what the painter wants to the viewer to see.

About the Artist

Born in New York City in 1894, Norman Rockwell always wanted to be an artist. At age 14, Rockwell enrolled in art classes at The New York School of Art (formerly The Chase School of Art). Two years later, in 1910, he left high school to study art at The National Academy of Design. He soon transferred to The Art Students League, where he studied with Thomas Fogarty and George Bridgman. Fogarty’s instruction in illustration prepared Rockwell for his first commercial commissions. From Bridgman, Rockwell learned the technical skills on which he relied throughout his long career. Learn more…

DIRECTIONS

Norman Rockwell Museum

9 Glendale Road Route 183

Stockbridge, MA 01262

413-931-2221

Download a Printable version of Driving Directions (acrobat PDF).

Important note: Many GPS and online maps do not accurately place Norman Rockwell Museum*. Please use the directions provided here and this map image for reference. Google Maps & Directions are correct! http://maps.google.com/

* Please help us inform the mapping service companies that incorrectly locate the Museum; let your GPS or online provider know and/or advise our Visitor Services office which source provided faulty directions.