Moving Pictures: A Conversation with Pixar Animation Artist Tim Evatt

November 20, 2020 – Written By: Rich Bradway

I first met Tim Evatt three years ago. I was working on a virtual reality (VR) project for the Norman Rockwell Museum. The project was a partnership between the Museum and the Academy of Art University in San Francisco. One of my “partners in crime” on this project was Chuck Pyle. Chuck is the director of the illustration program at the University. Chuck is also a member of the Museum’s National Council, an assembly of individuals who work with the Museum to expand awareness of the importance of illustration on our culture and society.

Chuck told me of an Academy of Art student who had made his way into and up the ranks as an illustrator at Pixar, a motion picture studio known for producing popular animated movies like Toy Story, Finding Nemo, and Cars, to name a few. This person was Tim Evatt, and on one of my many visits to the San Francisco area working on the VR project, Chuck scored me a visit to the famed studio to meet Tim.

Tim greeted me in the cavernous lobby of the main building at Pixar, which is named after Apple Computer’s founder, the late Steve Jobs. We walked through the public hallways of the studio looking at the work of all the artists on staff who had contributed to the film Coco, which was in theaters at the time. We looked at storyboard art, pencil and color studies, set designs, and 3D maquettes. I was like a kid in the candy store.

However, equally impressive was learning how much Tim was and is a true student of “golden age” illustrators like Norman Rockwell, J.C. Leyendecker, and Dean Cornwell. From an early age, Tim has looked to these artists for inspiration, a trait those artists had in turn for their own predecessors. I was floored not only by Tim’s knowledge for the history of illustration but also for this ability to identify the same artistic techniques of the masters in contemporary artists like Alex Ross.

Over the years, we continued to talk to each other about the golden age masters and how they continue to influence up and coming artists of today, whether they are aware of it or not. This past week, I decided to capture one of my conversations with Tim in anticipation of a virtual program that the Museum is planning to hold on Wednesday, December 2, 2020 at 7pm. During this conversation, Tim will talk about his career, and also about how Pixar goes about making animated movies.

The following is an edited transcription of the conversation.

Norman Rockwell Museum (NRM): When did you know you wanted to be an animation artist?

Tim Evatt: As a young kid, art was more like a teddy bear growing up. I would surround myself with art and watch movies and read comics. Growing up in the 1980’s, illustration was used on all of the box covers for VHS movies and video games. Illustration was still pretty prevalent in picture books too. School at times was very hard for me. Art on the other hand was an escape as I would draw what I was seeing all around me. It became part of my existence. After a while, as I got better, it became a means by which I could earn the respect from my peers. It wasn’t so much a decision as it was a realization at the very young age of 4 that drawing was something that brought me great joy and ultimately something I wanted to continue for the rest of my life.

NRM: You say the “Golden Age” illustrators were some of your heroes. Were there specific illustrators, and why and how did they inspire you?

Tim Evatt: My earliest memories of illustrations that I just loved looking at were these old picture books from the 1940’s, 50’s and 60’s about dinosaurs and cavemen. These books were illustrated by a Czech artist and illustrator by the name of Zdenek Burian. He did these amazing ink paintings. I was totally in awe that this artist could create images that made you feel in the moment – right there amongst the dinosaurs. Later on, when I learned about the art of Frank Frazetta, I realized that he was also inspired by the work of Burian. You can totally see it. It’s in his DNA.

Later on, growing up in Redlands, California, I would visit the Lincoln Shrine down the street. The shrine is a museum and research facility dedicated to the legacy of Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War. In one wing of the shrine, they have an original painting by Norman Rockwell titled the “The Long Shadow of Lincoln” in which the central focus of the painting is a disabled soldier, newly returned from the battlefield, who is contemplating the challenges of the postwar world. Around the perimeter of the painting, surrounding the solider, are allegorical representations of the blessings of liberty for which Americans were fighting. I would often sit there and look at the image. It is filled with elements that are quite symbolic. I would often think about what each person was doing and why their existence in the image mattered. This image then served as an introduction into a deeper examination of Rockwell’s work.

When you look at his career, it is truly amazing at how it evolved. I am personally struck by and fond of his portrayal of “characters” in his earlier works. Down the street from the Lincoln Shrine in Redlands is the Smiley Library, and if you go into the Children’s section you will also see prints of Rockwell’s work illustrating Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain. They emote an energy and personality that I think has inspired many artists since. As Rockwell’s career evolved, he focused less on the characters and more on a realistic representation of people, something that is prevalent in his Civil Rights work. This is something only a few artists could have pulled off with the success that Rockwell had.

Also at the Lincoln Shrine, if you look up in the lobby, you will see some murals by Dean Cornwell. I did not know it at the time who Dean Cornwell was but later in art school I grew a deep love for his work. I learned from Cornwell that the time of day and lighting can influence the design of an image. This is going to sound weird, but Cornwell could also emulate “smell” with colors. He could go to a barn and paint the “smell” of it. Aside from these uncanny skills, I am just blown away by Cornwell’s stamina. He worked nonstop. I can only imagine what his family life would have been, if he even had one at all.

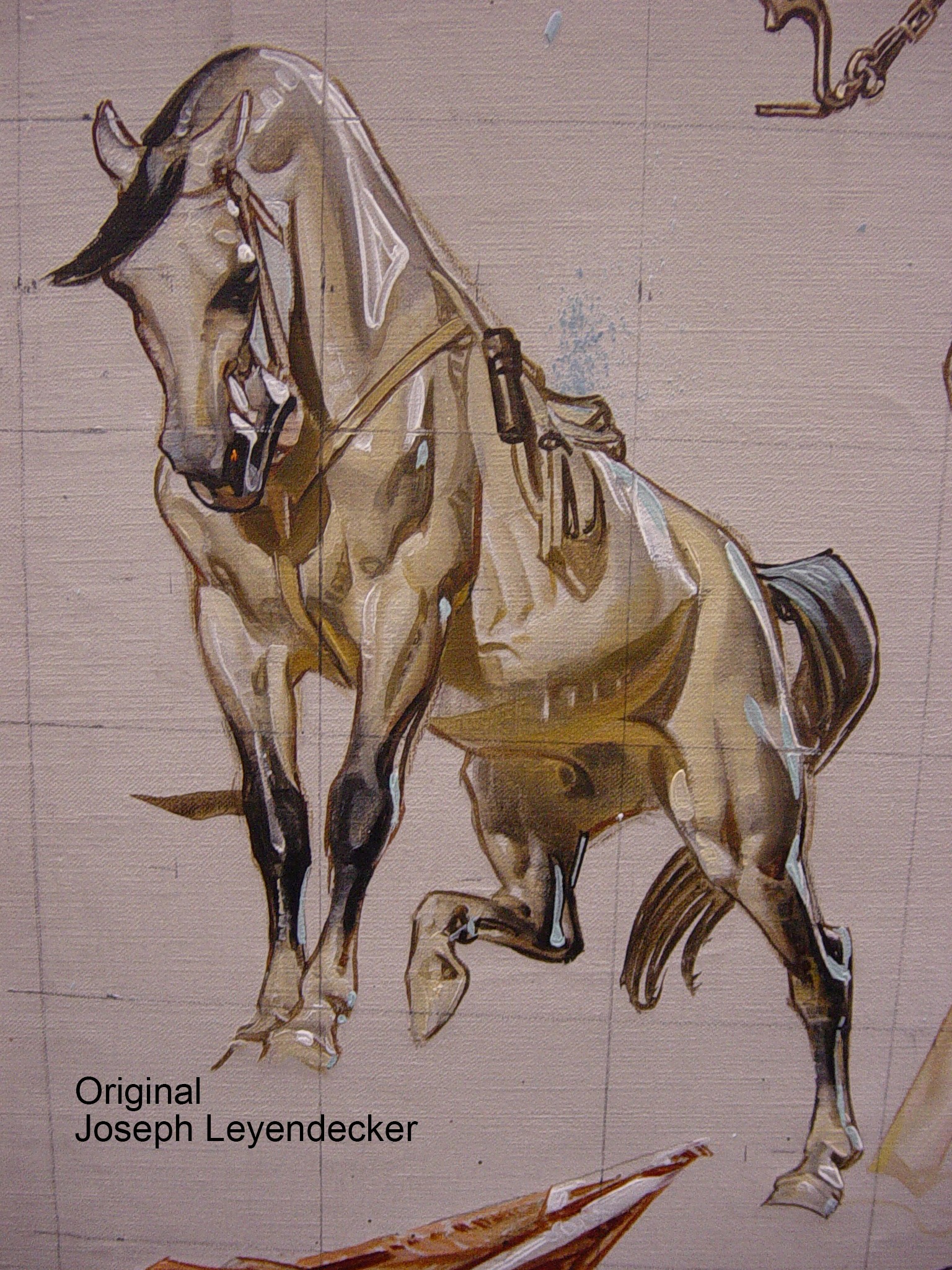

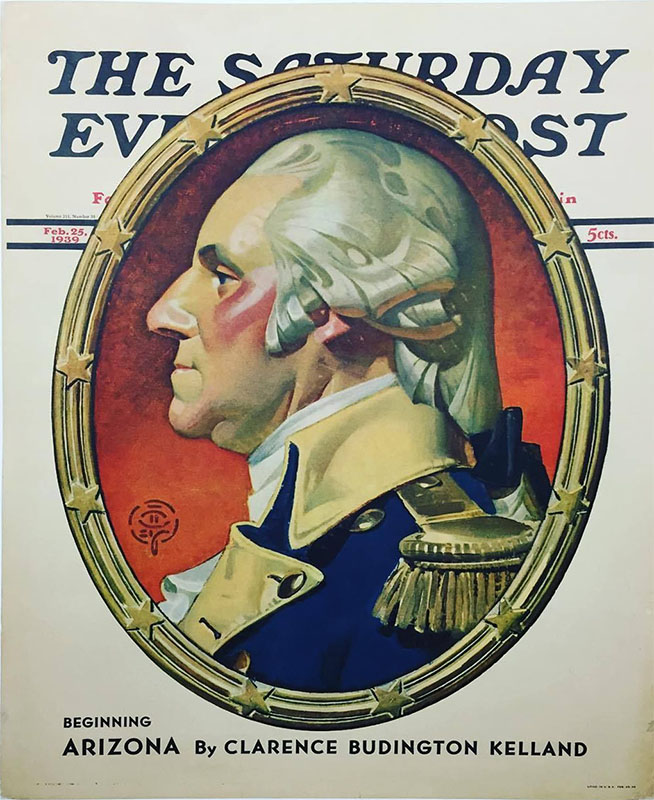

Once I got to art school, I discovered Joseph Christian Leyendecker or J.C. Leyendecker. I discovered that before there was a Norman Rockwell, there was a J.C. Leyendecker. Leyendecker had a unique style that is all his own- his ability to caricature, push design, and give everyday objects this high-quality look, just by his ability to accentuate forms. Leyendecker’s illustrations were more like color drawings than paintings. He had the background to do a lot of the mid-tone work to speed up his advertising commissions by being influenced by Charles Dana Gibson, Alphonse Mucha, and his teachers John Vanderpoel and William-Adolphe Bouguereau.

Aside from being an artist, I am student of basketball, and I easily equate Michael Jordan’s relationship with Kobe Bryant with Leyendecker’s relationship to Rockwell.

On his way to being one of basketball’s “Greatest of All Time” (aka “goat”) players, Kobe at a young age professed a desire to surpass his hero, the greatest “goat” of them all, Michael Jordan. He learned all of Jordan’s moves and through perseverance and hard work became one the game’s greatest players.

Rockwell was the same way. He emulated Leyendecker to a “T”. You can see some amazing resemblance in Rockwell’s early work to the vast output of Leyendecker’s career.

NRM: Do you have specific illustrations/images from these illustrators that hold a special place for you? Do any of these images find their way into your work?

Tim Evatt: Anything that Leyendecker painted!

When I was in Art School at the Academy of Art University, I spent a lot of time working on studies based off of Leyendecker’s images. The blocky cross-hatching of his backgrounds coupled with the immaculate and accentuated forms of his figures are a technique that has found its way into my work at Pixar.

A few years back after Pixar had come out with Toy Story 3, a few of us were asked to work on an animated TV special using the Toy Story characters. This special was called “Toy Story That Time Forgot”. The special was originally planned to be a six-minute short, but management liked the idea and suggested making it into a 22-minute holiday special. In this special, some new toy characters were needed called the “Battllesaurs”, which were dinosaur-themed action figures. They were like the 80’s toys I grew up with.

A number of us were tasked with designing the characters. Many of the initial designs looked too real. The director wanted to make them look like dinosaurs made out of plastic. For my design of the main character “ Reptillus Maximus”, I was totally influenced by Leyendecker’s football player from a Thanksgiving cover of The Saturday Evening Post. His dominant physique and his perfect form were an ideal look for the plastic action figure. It also didn’t hurt that I was designing a dinosaur either, thinking back on my love of Burian’s illustrations in those picturebooks about dinosaurs and prehistoric cavemen!

NRM: Can you talk about your training as an artist? When did you start your formal training? Were there any mentors?

Tim Evatt: In 2000, I headed to the San Francisco Bay area and attended the Academy of Art University. I studied under folks like Chuck Pyle, Randy Berrett, and Barbara Bradley. Barbara was a huge influence on me. In the 1950’s she worked with Coby Whitmore at the Cooper Studio in New York. She was also good friends with Al Parker.

I’m blessed I had the opportunity to sit with her telling me the times working in New York being in the bullpen cutting mattes for illustrations to be shipped to clients. Then getting the “break” and being able to get her chance to illustrate with her hero’s. She was able to break through and earned the respect of her peers, and she would go on to be a huge part of the DNA of the Academy of Arts and set the example for students on how to be professional artists.

Even in her 80’s, when I showed up, she could draw with her eyes closed. Her gouache paintings are unbelievable! She did not need Photoshop to assist her, no “CMD + Z” on any of it!

She was challenging at times. So many kids got chopped up by her! But if you survived and learned from her, you were on your way.

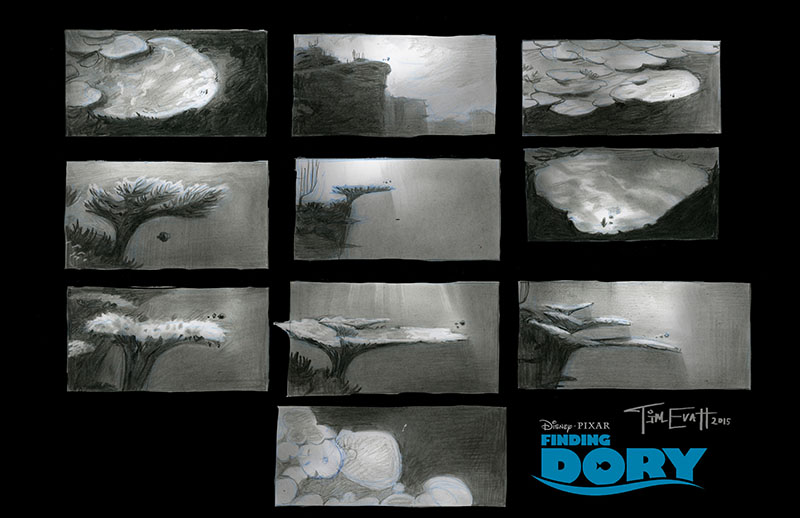

NRM: Without delving too deep in this as you will talk more about it in your talk for the Museum, Can you speak about your role as a set designer & production designer at Pixar?

Tim Evatt: As a set designer- it’s a fast and demanding job, creating the environment the characters can act on. We are beholden to the story. Wherever the story goes, we go with it.

It’s ideal to get a kickoff idea from the director on what they might envision. Art can also influence the story at times too. I’m kind of in the design’s legibility stage, to quickly give options and ideas to my production designer and be presentable to the director. Basically my work “starts the conversation” in the design process. Designs tend to be a rougher “shorthand” to generate ideas. Being too polished in a design can lock people into an idea that is too hard to work with.

Once we have a sense of what idea we want, I then go in and work on more polished renditions of the designs. 3D modeling has also been a tool to help rendering my images, so I could take my designs even further so that the production team could see how those designs might play out in the constructed environment.

When we talk about animation and illustration, although there is a lot of illustration throughout the creative pipeline, illustration is about mass-produced images and the final film is the ultimate illustration.

I’m lucky to say I’ve worked under all the Production Designers at Pixar- Bob Pauley, Harley Jessup, Ralph Eggleston, Bill Cone, Noah Klocek, Daniela Strijleva, Rona Liu, Steve Pilcher, and Don Shank. Pixar’s been a second school for me on film making. I’ve been Blessed and grateful I’ve learned from them & the whole Pixar art team!