Embedded: Illustrators and the Armed Forces

November 2, 2020 – Written By: Rich Bradway

With the ubiquity of cameras on cell phones, photography and video consumption, vis-a-vis digital photography and social media, is at an all-time high. It’s hard to scroll through one’s social media feed and not see selfies of other people, food photos from one of your friend’s latest meals, snapshots of some beautiful and exotic locale (or in the time of COVID, someone’s living room), a political ad, or even a meme. Even major news outlets, as we know them, are influenced and supplemented by personal photographs and videos from the public. You name it, photography is on the Internet, it is in your inbox, it is on your TV, your computer, and on your phone.

Since the mid-nineteenth century, photography has played a critical role in documenting our society and our history, establishing a visual record of global events and conflicts. It is hard not to forget seeing images of soldiers in battle, whether in Afghanistan and Iraq, Vietnam, Korea, and during World War I & II. Perhaps even worse than seeing the action as depicted, is recalling the outcome of those conflicts, the sacrifice of human life.

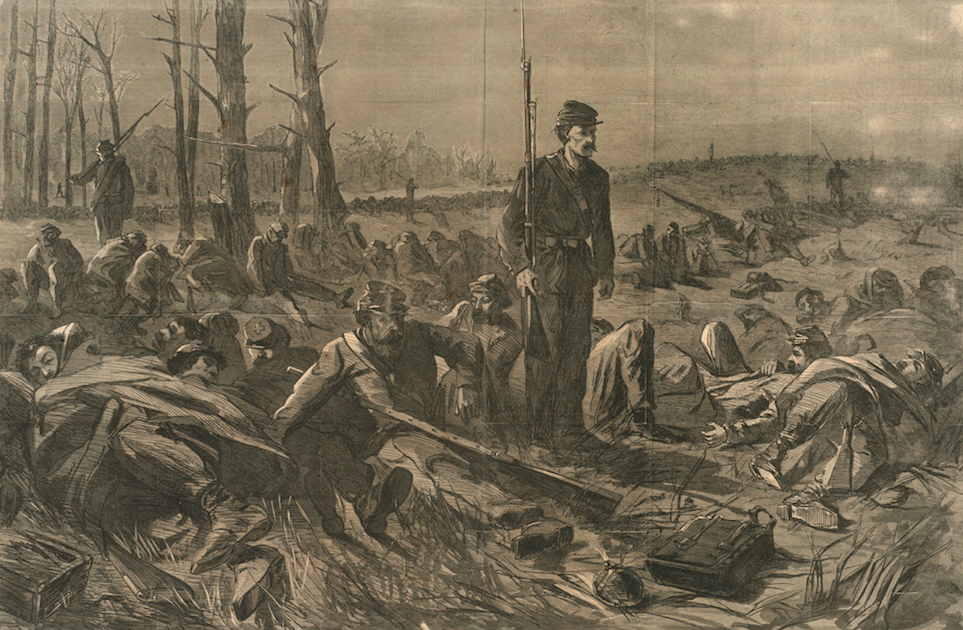

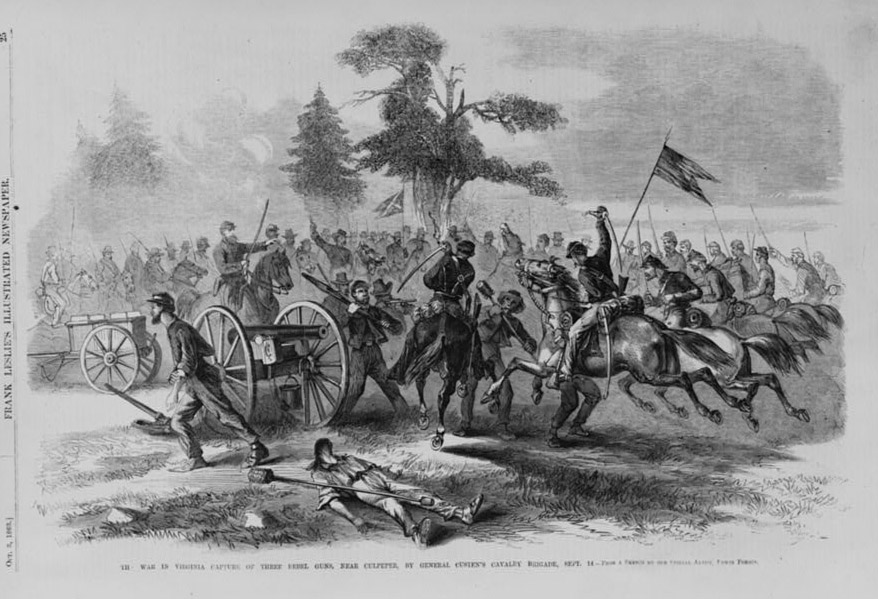

However, before photography became the fashion for documenting our collective history, illustrators were tasked with portraying these events for mass produced periodicals and newspapers. Though photography was prevalent during the American Civil War, as seen in the images by Mathew Brady, Alexander Gardner, and Timothy O. Sullivan, camera equipment was cumbersome and exposure time long. Illustration more fluidly captured battlefield action, as reflected in the work of some of the art world’s most noted creators. Winslow Homer, Alfred Waud, and Edwin Forbes got their start by documenting the Civil War.

During World War I, despite greater access to photography, illustrators were even recruited by the United States government to participate in the United States Army Combat Artists Program via the American Expeditionary Forces. Illustration could be edited to reflect the messages that the government wanted to convey to the public back at home. Art editors and illustrators were integral to the government’s messaging and propaganda machine.

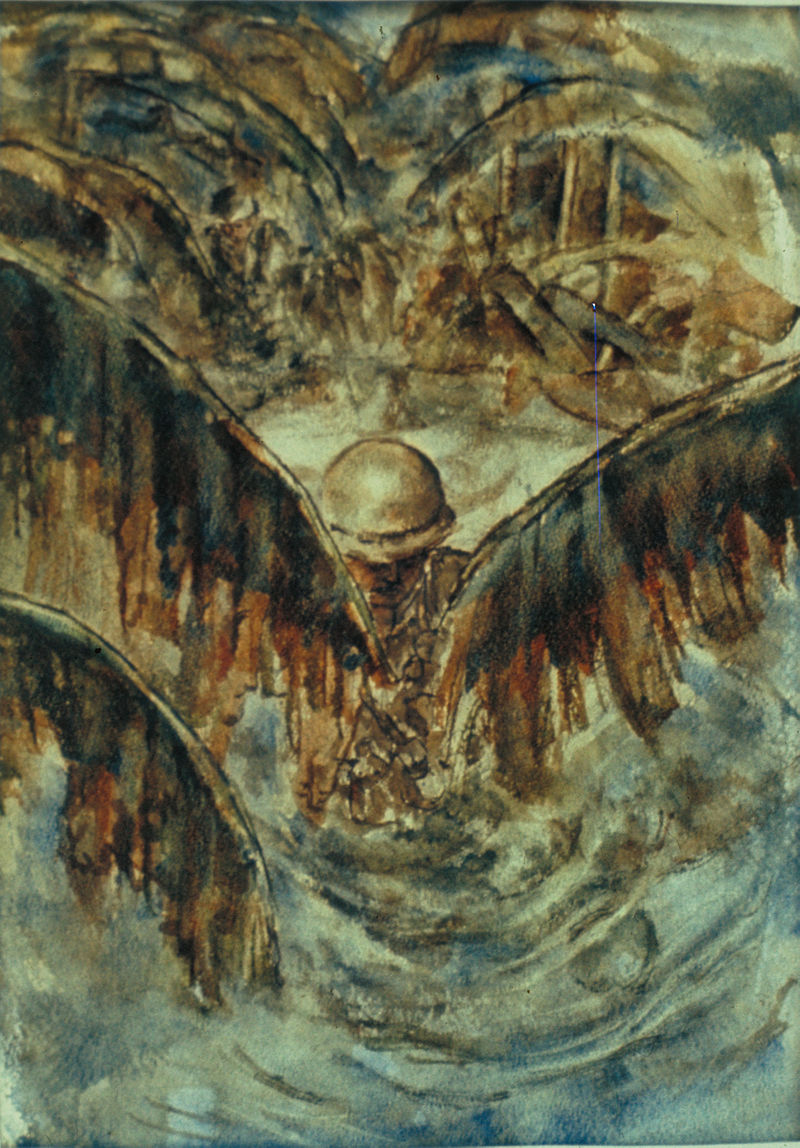

However, not all artists obligingly drew images the government wanted people to see. In the fall of 2015, the Norman Rockwell Museum staged a comprehensive exhibition featuring the art of Harvey Dunn (1884-1952). Born on a homestead near Manchester, South Dakota, Dunn left the farm to study at the South Dakota Agricultural College and the Chicago Art Institute before becoming one of Howard Pyle’s most accomplished students—along with N.C. Wyeth and Frank E. Schoonover. Commissioned as a Captain in the Engineer Reserve Corps during World War I, Harvey Dunn was thirty-three years old and had no previous military training.

Stationed at Neufchateau, France, he brought along a sketch box of his own design, fitted with drawing paper on a cylindrical scroll that allowed him to move more easily from one drawing to the next. Attached to Company A of the 167th Infantry, he faced fire himself and recorded the men’s struggles and casualties first-hand. These pressures left little time to finish works or send art back to the United States for publication as intended. Artists expected to have time to paint and draw from their rough sketches once retired from duty, but after the Armistice, the military’s interest in the project waned. Discharged in April 1919, Dunn returned home on the U.S.S. North Carolina, and would ultimately complete thirty-three paintings based upon his wartime experiences. Rather than focusing only on the drama of soldiers in action that had been envisioned by the military, Dunn faithfully recorded a full spectrum of emotions and experiences in his art, which is powerful, empathetic, and heartfelt. In 1928, Dunn completed several of his war compositions for The American Legion Monthly, which published his dramatic portrayals inspired by first-hand experience on its covers.

Through the years and other conflicts, the work of illustrators became a critical and essential tool in the government’s messaging. During World War II, the U.S. government established the War Art Unit (still effectively the U.S. Army Art Program) and War Art Advisory Committee (in collaboration with the United Kingdom) that was made up of 42 artists—23 active military and 19 civilians. Its sole mission was to keep the American public invested in the war effort and focus on achieving a successful outcome.

However, as the war dragged on and the financial and human toll weighed heavily on the country, Congress withdrew funding for the Art Programs in 1943. At which point, Life magazine and Abbott Laboratories, a large medical supply company, took up the effort to create a visual record of the American military experience at war.

Some of the most iconic images from that period were illustrations by noted artists, a number of which are currently on view in the Museum’s “Norman Rockwell: Imagining Freedom Exhibition“. Works by Norman Rockwell, Mead Schaeffer, Arthur Szyk and Boris Artzybasheff and other home front artists are featured in our galleries along with images by embedded combat artists and soldiers like John Falter, Thomas Lea, and Fred Eng.

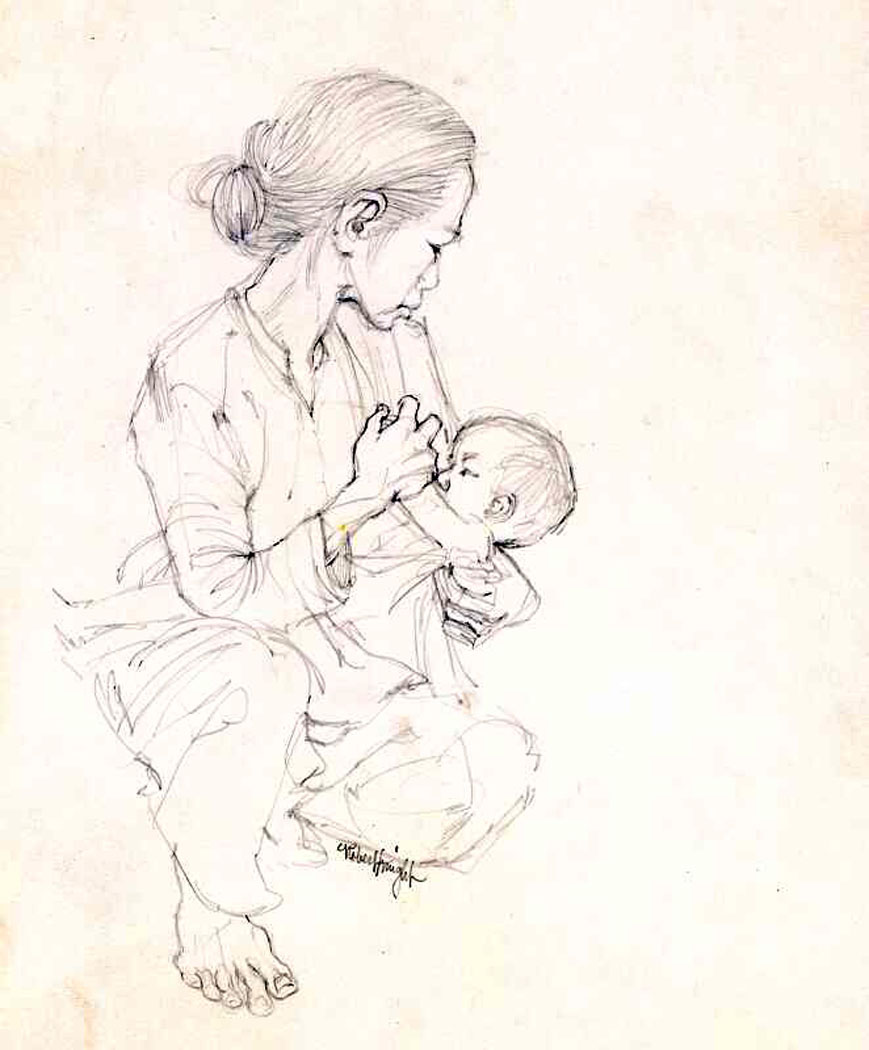

Combat Artists were still active during the Vietnam War as part of the United States Army Art Program. Most of the participants in this program were active military, who depicted troop activities from 1965 through 1970. After the war, civilian artists and retired regular soldiers who used art as a means of self-expression and therapy to cope with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were added to the Art Program, reflecting the extensive personal toll the war inflicted upon them.

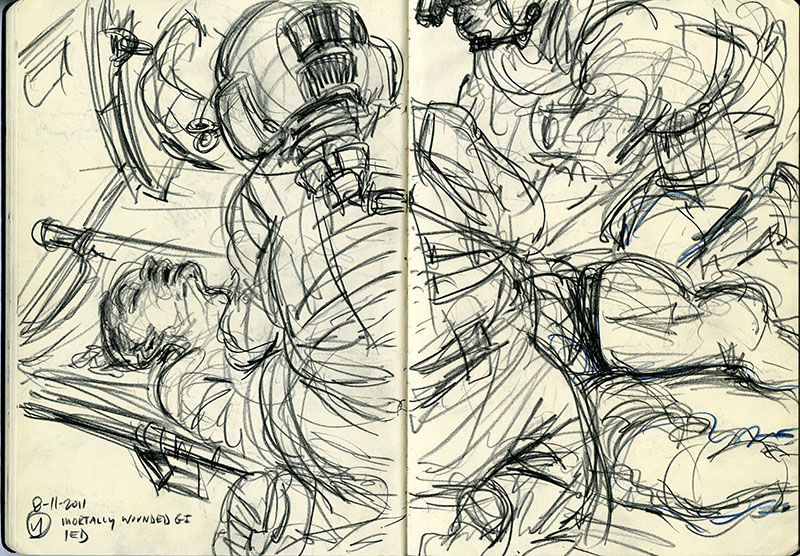

On Veteran’s Day, November 11, 2015, while the Harvey Dunn exhibition was on display at the Museum, I was fortunate to meet Victor Juhasz. A successful political cartoonist, Victor’s art is seen in many major media outlets, but perhaps most noted to me was his work for Rolling Stone. Victor gave a presentation as part of the day’s programming, sharing stories of his participation in the United States Marine Corps Combat Art Program. Victor was never a soldier, but his style of illustration lends itself in depicting the emotion, action, and immediacy of combat situations. His work ethic, respect for the subject matter, and the incredible output of his work has been an inspiration to the artist/soldiers in the program.

Interview with Victor Juhasz at Norman Rockwell Museum, November 11, 2015.

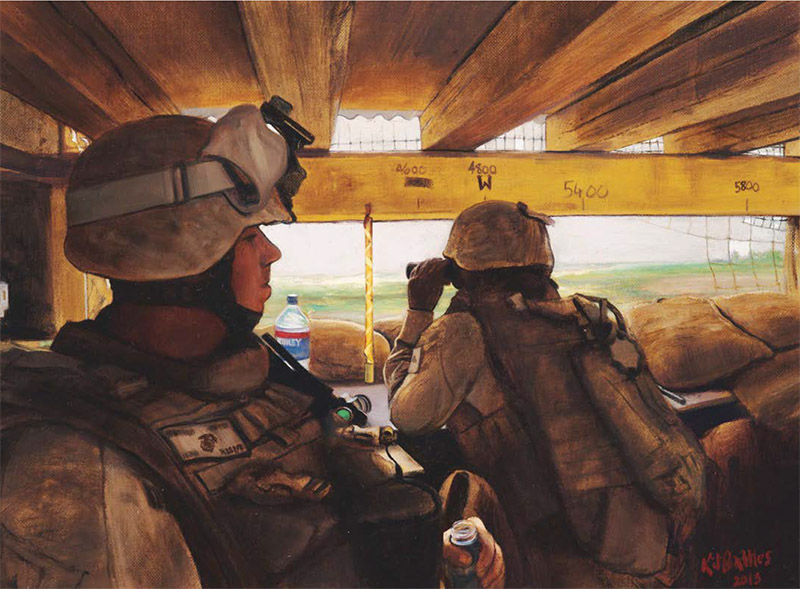

Victor’s work also inspired me to investigate United States Marine Corps Combat Art, which led me to discover that the program is still quite active, comprised of incredible work by today’s talented visual commentators. Their art and subject matter has given me a deeper respect not only for our nation’s men and women serving in the armed forces, but also for the scope of work that they are tasked with doing.

Like Victor, I was never a soldier, but my father was. He served in the occupation of Europe after World War II. His responsibilities ranged from working in ordinance, to the motor pool, and finally in graves registration. His tasks in these areas were also quite diverse from the thoroughly tedious and mundane to the most graphic and shocking of his life.

While each soldier’s experiences contribute to the war stories we all hear and appreciate, it is the full spectrum of the work they selflessly undertook, sometimes paying the ultimate sacrifice that truly makes them heroes.

I have always been gratified that Veteran’s Day and Thanksgiving Day take place in the same month. They remind me to be thankful not only for the personal blessings in my life, but also for those who serve our country.

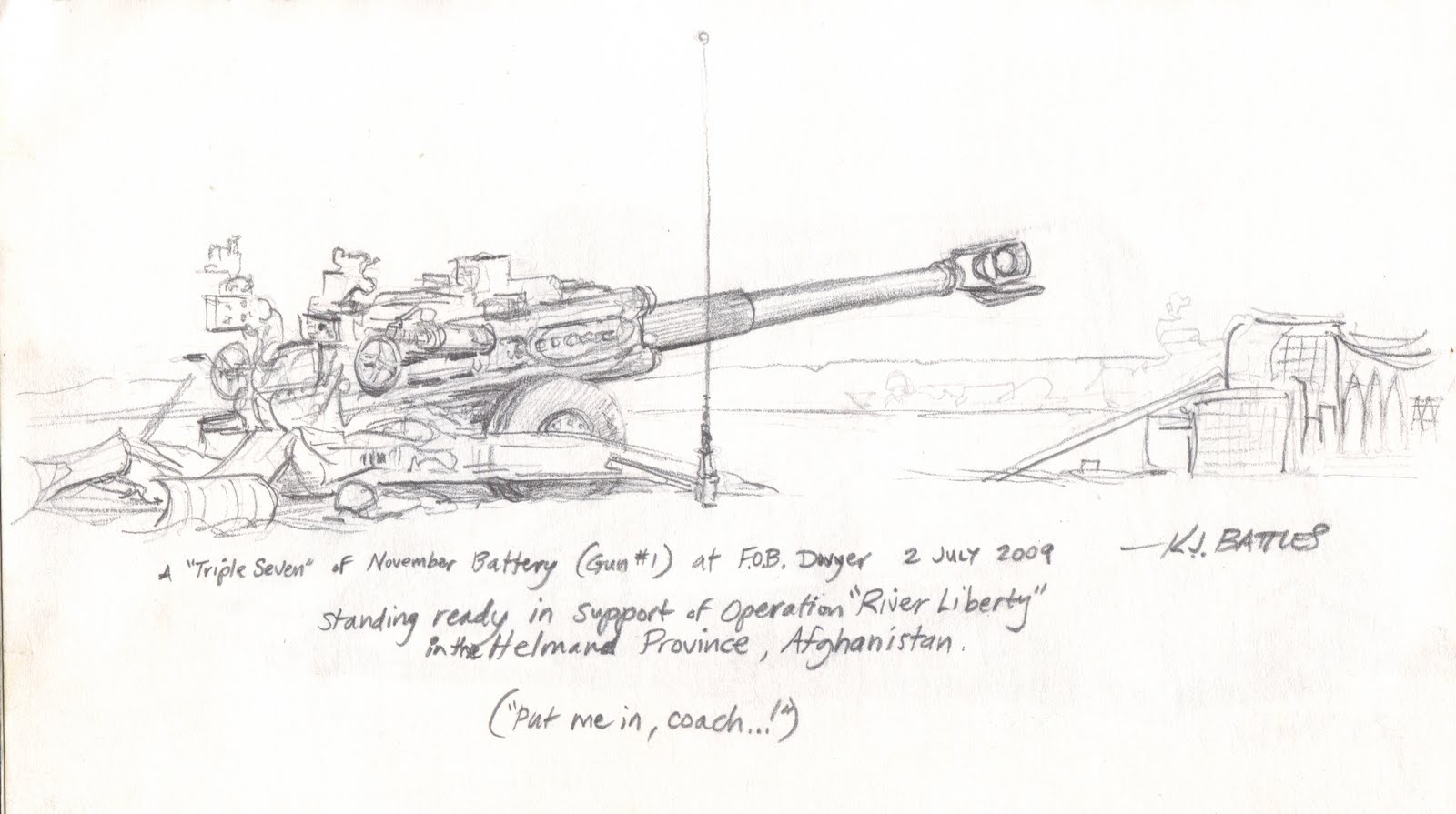

This Veteran’s Day, I will add “combat artists” to those ranks because they bring the full spectrum of military service to life in illustration unlike no other medium. On November 11, 2020, at 1pm EST, the Norman Rockwell Museum will host a virtual program that I will be moderating and will feature some of today’s most accomplished combat artists, including: Kristopher Battles, Michael Fay, Victor Juhasz, Elize McKelvey, and Steve Mumford.

Kristopher Battles

![Fred Eng - Casablanca Portfolio: [Soldier entering building ruins], 1944](https://www.nrm.org/wp2016/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/NRM.2012.4.42.800x800_Eng.jpeg)