BTW Berkshires:

Original Sisters unite in Anita Kunz’ paintings

Original Sisters unite in Anita Kunz’ paintings

by Kate Abbott

December 5, 2024

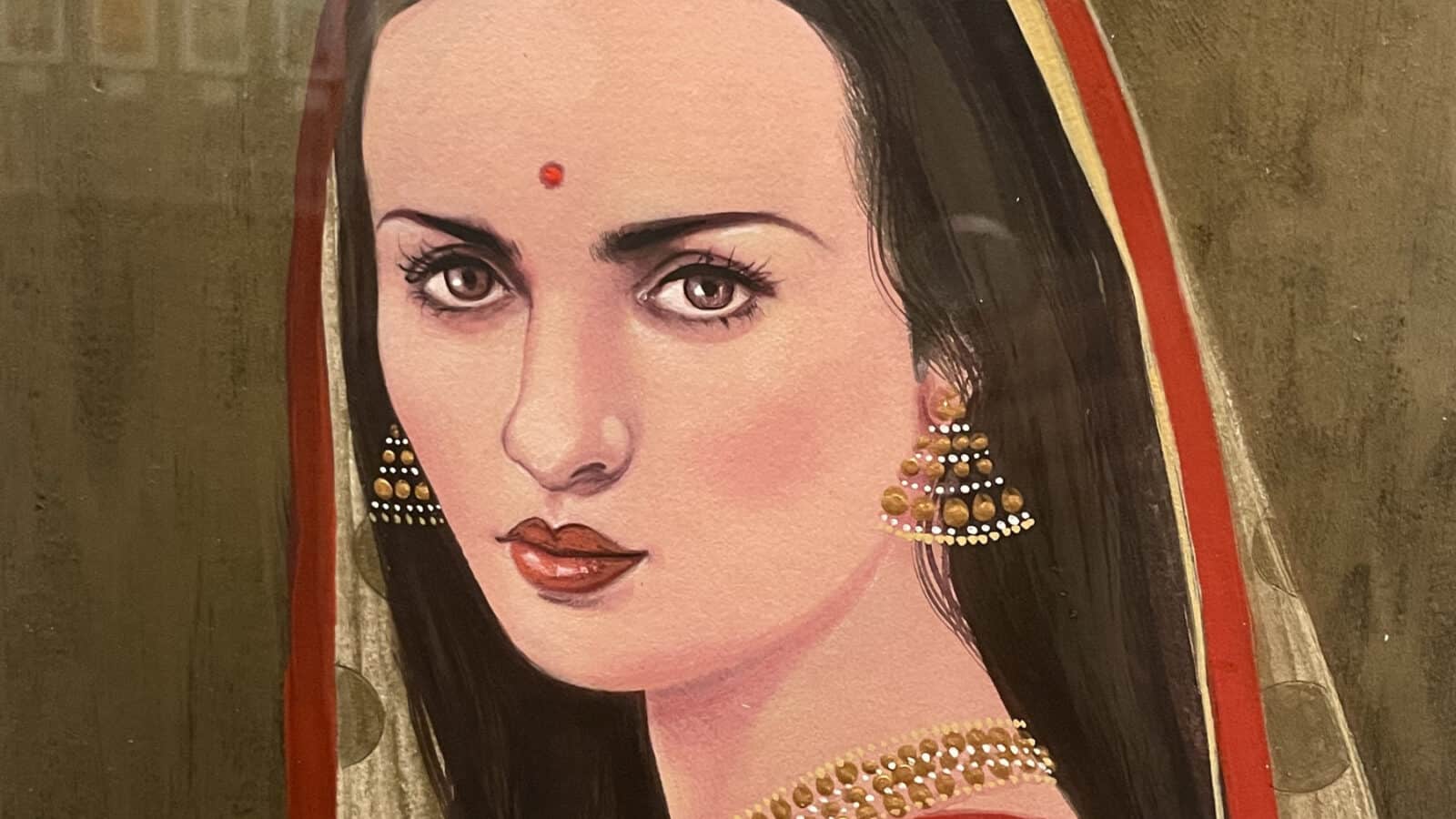

It’s November 1936, and Amrita Sher-Gil is winning recognition throughout India as an artist. She was drawing crowds in Mumbai for her paintings, a woman sleeping on her back, three girls sitting together with sun washing over a cheek, a shoulder and bringing out the nap of cloth with a vivid sense of heat and light.

As her name spreads across the country, she is standing awed in the Ajanta caves in Maharashtra, absorbing colors imagined 2500 years before.

All of the women in the show have their own passionate and vivid lives. The show shares some glimpses of their stories here, woven through the paintings, and in the catalog, Original Sisters: Portraits of Tenacity and Courage, and I have also looked for their own voices. Amrita Sher-Gil’s quote here comes from a letter in Yashodhara Dalmia’s biography, Amrita Sher-Gil: A Life. Anna Akhmatova’s poems come from a collection translated by Stanley Kunitz and Max Hayward, and Shamsia Hassani’s words are her own.

She described them as “painting with a kernel,” an essential core. Women kneel together, gesturing as they talk. Padmapani, the Bodhisattva of compassion, holds a lotus with petals brushing skin and a background of firelight and the green of water running through limestone.

“I think all art, not excluding religious art, has come into being because of a sensuality so great that it overflows the boundaries of the mere physical,” Sher-Gil writes to a friend. “How can one find the beauty of a form, the intensity or subtlety of a color, the quality of a line, unless one is a sensualist of the eyes?”

Imagine these women together 90 years later — and around them gather 280 more, women coming together across time and space.

Three thousand miles away, in Odesa, in the Ukraine, Anna Akhmatova is returning to writing poems after 10 years away — and she is embarking on a requiem she will write for 25 years. She will become an international voice, and in the last years of her life she will be nominated for the Nobel Prize in literature for two years running.

But around her now, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin is ‘purging’ the country, having hundreds of thousands of people arrested, killed, sent to labor camps, including her husband and her son. In 1936, she has lived through revolution and a world war, censorship and terror. “Now all’s eternal confusion,” she says. And she is still writing.

Imagine these two women together in one room, 90 years later — and around them gather 280 more, women coming together across time and space. Internationally recognized illustrator and artist Anita Kunz has brought a labor of love to the Berkshires in ‘Original Sisters,’ a new exhibit of portraits at the Norman Rockwell Museum, guided in this incarnation by the museum’s Curator of Exhibitions, Jane Dini.

As a Canadian artist living and working in London, New York and Toronto, Kunz has created socially and politically themed work, in her own words, for publications from Time magazine to the New Yorker and Rolling Stone and magazines from Switzerland to Korea and Japan.

‘How can one find the beauty of a form, the intensity or subtlety of a color, the quality of a line, unless one is a sensualist of the eyes?’ — Amrita Sher-Gil

And here she has reached out to a community of women through centuries and around the world, at a time when she has felt a need for courage. She began this work in the pandemic, she said. As the lockdown took hold, she thought of women living in dark and difficult times, and she wanted to honor their strength.

So she began to paint a new woman each day. in these rooms, women stand together who have commanded fleets of ships and mapped the human genome and the night sky. They have uncovered fossils and learned the structures of metamorphosis.

“Original Sisters is a love note to women on whose shoulders I stand,” Kunz said.

Internationally acclaimed for fiction, Nella Larson became known for her novels during the Harlem Renaissance. Press photo by Kate Abbott, courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

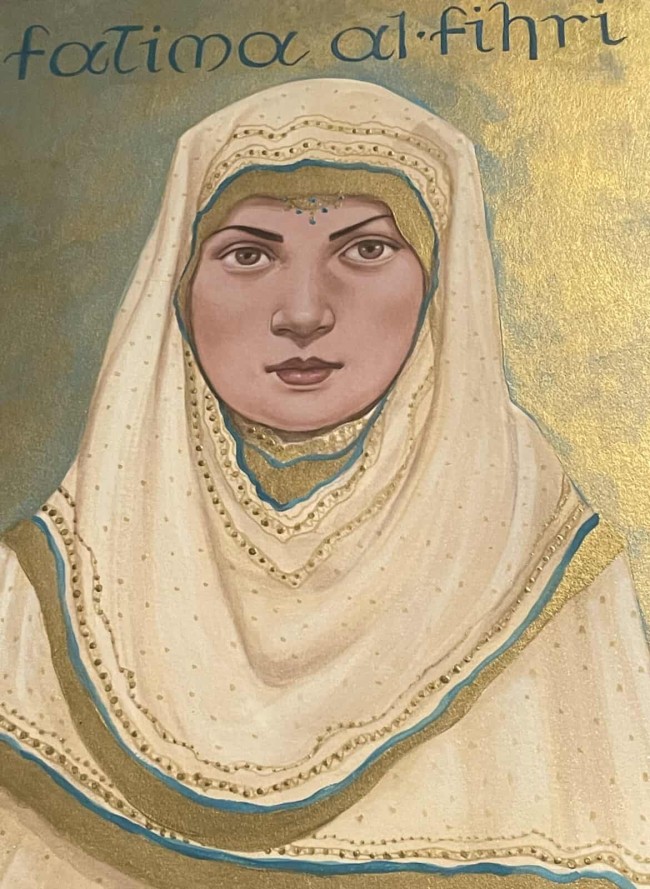

Fatima al-Fihri is known as having founded al-Qarawiyyin, the oldest continually living university in the world, in Fez, Morocco, in 880 CE. Her university holds the world’s oldest library.

And standing here within a few feet of her, within this generation Shamsia Hassani, an Iranian born artist, has become the first graffiti artist in Afghanistan.

In her own words, Hassani’s art “gives Afghan women a different face, a face with power, ambitions and willingness to achieve goals.” She often paints women as well, each one bright with energy and color, “a human being who is proud, loud, and can bring positive changes to people’s lives.”

‘Original Sisters is a love note to women on whose shoulders I stand.’ — Anita Kunz

Her artworks have inspired thousands of women around the world, she says, and she has motivated hundreds of Afghan artists to bring in their creativity through her graffiti festival, art classes and exhibitions in different countries around the world.

As Kunz’ own work has grown, she has met more and more women new to her. Over and over, she said, she would find herself thinking, “She is awesome — how didn’t I know about her?”

She found suggestions from friends in many fields, she said. She scoured the internet, blogs and searches, and delved into a series of New York Times obituaries that should have been written, commemorating women who have been recovered for history.

“Women have been responsible for remarkable achievements in all areas of life,” she opens the catalog to Original Sisters, “and have made major contributions throughout the ages. Yet … they are not known or remembered in the way they should be.”

Wall texts in the show reveal patterns in the lives of many of the women around her, deeply intelligent, forceful, active in ways that can define and reshape worlds far beyond their home communities, and protect them, and transform them.

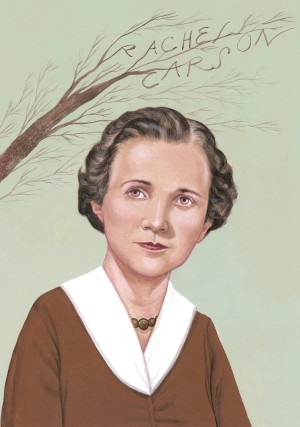

Rachel Carson, the environmentalist known for Silent Spring and her work in inspiring the Environmental Protection Act, stands looking into winter trees in Original Sisters.

Alessandra Korap Munduruku, a human rights defender and leader of the Munduruku people of the Tapajós River Middle Course, leads efforts as an activist globally and at home, and has protected more than 400,000 acres of rainforest.

Rachel Carson, walking in tide pools, set currents in motion that would lead to the Environmental Protection Act. Autumn Peltier has addressed the Global Landscapes Commission at the UN as chief water commissioner of the Anishinabek Nation.

These women are scientists and activists and leaders of political movements, and they are musicians and writers, athletes and astronauts. And they are artists — the kinds of artists, Kunz said, that she had never learned about before she started down this path.

The editors she mentioned in the tour as frequent collaborators are universally men, and so have been many of her mentors in the art world. In studying art history, she said, her professors and the artists she studied were overwhelmingly white and male.

“I never had any women teachers,” she said, “and the art history I received was mostly Western and European artists.”

‘Women have been responsible for remarkable achievements in all areas of life, and have made major contributions throughout the ages. Yet … they are not known or remembered in the way they should be.’ — Anita Kunz

In her own work, she has pushed some of those boundaries. Twenty years ago she became the first women artist celebrated in a solo show in the Library of Congress.

Art and humor illustrators in the press have a long history of keeping a check on people in power, she said — an influence she feels has weakened in the U.S. in the past 20 years, since September 11, in part because editors have acted with less courage and have imposed more restrictions, and artists have lost the freedom to create with strong voices on many platforms.

This pattern has become another reason she has felt the need to work in her own space, on her own terms. She has made an international career in print illustration and in satire and humor, she said, and though some of the editors she works with can give their artists flexibility in their work, as she has become more established, she has wanted more time to evolve her own ideas.

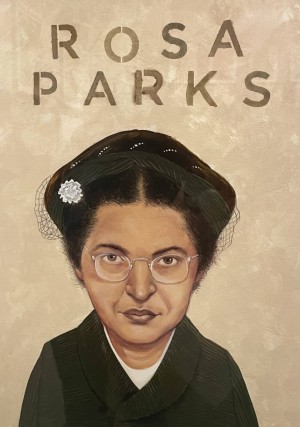

National Civil Rights leader Rosa Parks, known for her role in instigating the Alabama bus boycott, worked with the NAACP as an investigator and lead a nationwide campaign against the sexual violence that Black women experienced at the hands of white men. Press photo by Kate Abbott, courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

In 2017, she painted the Women’s March from her own direct experience. She remembers the charged excitement of the downtown filled with so many women that they overflowed public spaces with a positive and active energy.

And then Covid came. And she began a new search for creative life force. At the Faison artists residency on Peaks Island in Maine, she heard for the first time of Jane Bates, a trans woman who lived here. Kunz looked for more of her story and could find very little.

“How many stories have been lost?” She said.

So she began to paint women she felt should be known. She learns and celebrates their stories, their brilliant vigor and pleasure, curiosity and beauty, for their grit and love of life. Walking through the rooms, she traced lineages and found kinship among them.

Here is Sojourner Truth — born into slavery in New York State 10 years after Elizabeth Freeman led Massachusetts to declare it illegal under the new state constitution — speaking across the country for abolition and women’s rights.

And here, close enough to call to her, Dorothy Height is leading the National Council of Negro Women in national efforts to end lynching. And Billie Holliday is singing Strange Fruit in a Greenwich Village nightclub, singing in the dark with the light shining on her.

As she explored, Kunz would learn about women who have saved lives and reshaped countries and ways of being. Looking back across four years, recalling moments that stand out for her, she recalls first encountering Frederika Dicker-Brandeis, an artist and teacher imprisoned in the Theresienstadt ghetto during the Holocaust.

Dicker-Brandeis brought art supplies and taught children to draw, as a way to help them cope with trauma and dislocation, the loss of their families, illness and hunger and fear. She would guide them to draw a world beyond the one they were living in. Many of them did not survive, but their drawings have.

Kunz felt humbled by her story and her persistent spirit. And she has found such courage around the world, she sais. Theresa Kachindamoto, Senior Chief if the Dezda District of Central Malawi in East Africa, has dissolved more than 2000 child marriages. When she was appointed chief, Kunz said, she was seeing 12-year-old girls who had already been forced to have children She has faced down threats of violence, and she has convinced chiefs to end these practices and fought for the education of young women.

Shannon Holsey, president of the Stockbridge Munsee community of the Mohican Nation since 2015, also serves now as president of the Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Council, which represents 11 member communities with a land base of c. 1 million acres across 45 counties. Press photo by Kate Abbott, courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum

And here in the Housatonic River valleys — Kunz celebrates women growing culture and freedom here in the hills. At the Norman Rockwell Museum, she presents three new portraits.

Shannon Holsey, president of the Stockbridge Munsee community of the Mohican Nation, has come to the opening to recognize her own. She has served as president since 2015, and she also serves now as president of the Great Lakes Inter-Tribal Council, which represents 11 member communities with a land base of about 1 million acres spanning 45 counties.

Beside her painting, Elizabeth Freeman stands at her shoulder. In 1781, she led the fight to proclaim slavery illegal in the commonwealth of Massachusetts, bringing the case to the state supreme court at a time when no woman could, let alone a woman of color.

And halfway between them, at the turn of the 20th century, Edith Wharton is writing her novels in bed, bicycling over the ridges and reading Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass on the terrace at dusk.

Someone who knows the local byways may find more connections here. Maria Tallchief performed as the firebird at Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival in the vivid crimson she wears, and within a few years, Lorraine Hansberry would be writing A Raisin in the Sun at Festival House in Lenox.

In the 1950s and 1960s, as the country shook with the Freedom movements and passed the Voting Rights act, across the ocean, Akhmatova finally won free enough of censorship and threat to her family and loved ones to publish a form of her Requiem.

She writes with sadness and love, as in an earlier verse she imagines Lot’s wife as a woman loving the land where she has lived and worked with her hands and come out to sing with her neighbors in the streets, where she has held her daughters when each one was newborn.

Akhmatova would have known how it feels to hold an infant to nurse on a winter morning, and to stand in protest, to face fear for her own life and for her son, and for her freedom — and to glory in her strength of mind, and to create for the burning love of making.