The Boston Globe Reviews What, Me Worry?

STOCKBRIDGE, MA — September 5, 2024– Norman Rockwell has a cherished place in the American imagination. So does MAD magazine. That Rockwell and MAD are as different as a Windsor chair and a whoopee cushion makes their unexpected interaction all the more fun. That interaction takes the form of “What, Me Worry? The Art and Humor of MAD Magazine,” which runs at the Norman Rockwell Museum through Oct. 27. Five ebulliently overstuffed galleries offer MAD layouts, drawings, toys, videos, back issues, board games, copies of foreign editions. It’s a horn of plenty of laughs. “What Me, Worry” is the (very) rare museum show in which visitors’ laughter is audible.

The Rockwell/MAD interaction may be unexpected — but not, as it turns out, a case of museum matter meeting magazine anti-matter. Rockwell was one of the foremost illustrators of the 20th century. His namesake museum is dedicated not just to his work but the art of illustration generally. MAD having been a showcase for illustration — from caricatures to cartoons and much else besides — it makes sense that there should be a show about the magazine at the museum. However, there’s also an unexpected personal connection, and it’s one of the great minor magazine might-have-beens.

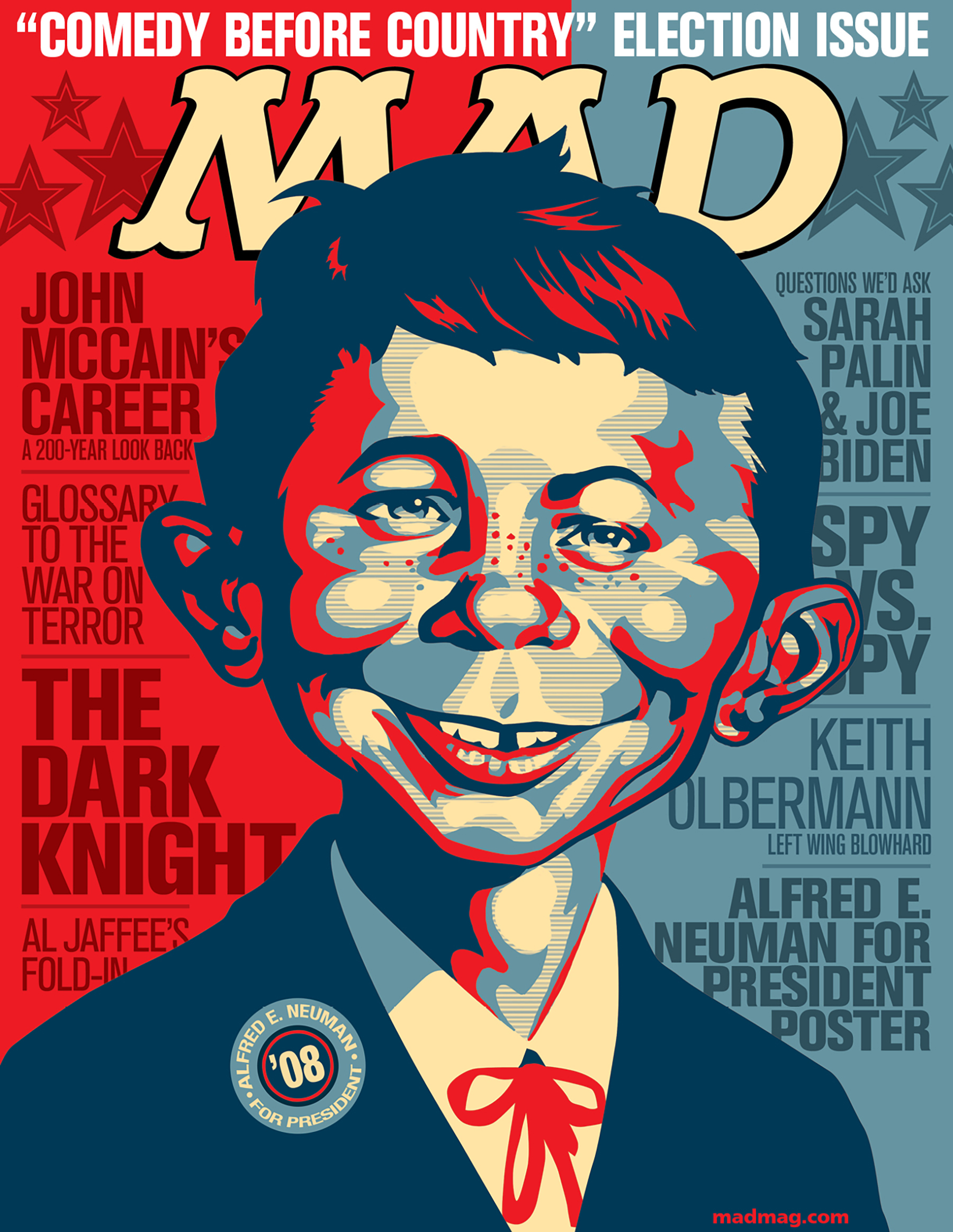

“What Me, Worry?” is the enduring motto of MAD mascot/cover boy Alfred E. Neuman. Amiably subversive, unflappably clueless, he’s the missing link between Huck Finn and Bart Simpson. One look at him, and you know that MAD is a humor magazine. That look also tells you what kind of humor to expect: proudly sophomoric, rarely subtle, and often extremely funny.

In 1964, MAD approached Rockwell about rendering “a more realistic and definitive Alfred.” The proposed fee was $1,000 for a charcoal sketch; then, if that worked out, $2,000 for an oil portrait. That was serious money. Adjusted for inflation, the first fee would be slightly more than $10,000. Rockwell was tempted, then backed out. “I hate to be a quitter,” he wrote, “but I’m afraid we would all get in a mess.” (What, him worry? Apparently so.) For better or worse, no whoopee cushion would grace that Windsor chair.

MAD began as a comic book, in 1952, and became a magazine in 1955. In 1973, its circulation hit 2.4 million. In its beneath-the-grown-ups’-radar way, it was as much of a boomer media phenomenon as Sports Illustrated, TV Guide, or Playboy. In fact, Hugh Hefner hired away MAD’s first editor, Harvey Kurtzman.

The magazine had many celebrated features, most notably its movie and TV parodies and the fold-in that ran on the inside back cover. The fold-in was the work of Al Jaffee, one of the magazine’s stars, along with Don Martin, Dick DeBartolo, Dave Berg, and Antonio Prohías, originator of another standby, “Spy vs. Spy.” There were also contributors you wouldn’t expect, such as Frank Frazetta and Charles Schulz. The show includes a whimsically unMAD-like Schulz drawing that ran in 1964.

Jaffee was responsible for what may be the quintessential MAD feature, “Al Jaffee’s Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions.” Forget spy vs. spy. Here’s snappy us (MAD contributors and, by extension, readers) vs. stupid them (everyone else).

MAD was as much state of mind as magazine: savvy yet innocent, a bit hyper, forthrightly goofy, insolent yet fundamentally good-natured. Taken together, most of those attributes might be described as adolescent, but that word has never quite applied to MAD. An adolescent sensibility, at least of the adolescent-guy sort (and MAD readers and contributors have been overwhelmingly male), tends to be dominated by thoughts of the “nudge, nudge, say no more” variety, as Monty Python so memorably put it. Yet sex and innuendo have never been MAD’s thing.

That’s a crucial point. It meant MAD could retain an essential innocence without in any way seeming naïve. That combination is as appealing as it is rare. It also made the magazine irresistible to smart-aleck 12-year-olds (of any actual age). In “Moby-Dick,” Ishmael famously calls a whaling ship “my Yale College, my Harvard.” Others, looking for a different kind of harpoon, had MAD. It provided a unique and skeptical tutelage in the workings of politics, popular culture, advertising, social mores. The longtime Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter once called MAD “part of the oxygen we breathe.” Carter was a cofounder of Spy magazine, a publication in some ways unthinkable without the example of MAD. It wasn’t the only one.

Attentive MAD fans surely noted an absence from that list of prized contributors: the nonpareil Mort Drucker. His “caricatures have never been nor will they ever be equaled,” Steven Spielberg has said. George Lucas has called Drucker’s caricatures “the best, and he is the artist that defines MAD for me.” Lucas isn’t the only one who feels that way. Appropriately, one of those five galleries is entirely devoted to Drucker’s work.

Caricature is an odd enterprise. To succeed, it has to simultaneously reduce and exaggerate, dismiss and embrace. Drucker didn’t just make that balance look easy. He made it look inevitable. He once explained how he went about drawing his movie parodies: “I become the camera and look for angles, lighting, close-ups, wide angles, long shots — just as a director does to tell the story in the most visually interesting way.” The “What Me, Worry” catalog deserves special praise. It’s made up to look like a copy of the magazine. Does it include a fold-in on the inside back cover? Duh, of course it does (speaking of snappy answers to stupid questions).

By Mark Feeney