The Berkshire Eagle

REVIEW: Norman Rockwell Museum’s ‘What, Me Worry?’ defines MAD magazine’s importance in the American zeitgeist

Stockbridge– June 20, 2024– It’s an election year, so perennial presidential candidate and MAD magazine cover boy, Alfred E. Neuman, has once again thrown his hat in the proverbial ring.

The imp-faced redhead has been a “write-in candidate” every presidential election since 1956, when he rst graced the satirical magazine’s cover with his trademark slogan, “What, Me Worry?”

His headquarters of choice this election season?

You’ll find him amongst some 250 original illustrations and cartoons, alongside magazine covers and ephemera that make up the exhibition, “What, Me Worry? The Art and Humor of MAD Magazine,” on view at the Norman Rockwell Museum through Oct. 27.

If you think the freckled-faced, gap-tooth magazine mascot is too lowbrow for the Rockwell Museum, think again! The show, co-curated by Stephanie Haboush Plunkett, deputy director and chief curator of the museum, and illustrator Steve Bodner, is a perfect t for a museum celebrating illustrators of every ilk — even those who refer to themselves as “The Usual Gang of Idiots!”

On newsstands from 1952 until 2018, MAD published 550 regular print issues, along with numerous compilations, paperbacks and other print projects. In 2018, MAD was rebooted as a subscription-based publication that heavily utilizes compilations of past material with a few new satirical pieces interspersed within.

“This is, we believe, the first full retrospective of the history and cultural impact of MAD magazine, which was published in print for 50 years and is still online and in uencing new generations today. Our mission is devoted to illustration and this summer exhibition focuses on the satirical ingenuity and enduring cultural legacy of MAD,” said Laurie Norton Moffatt, director and CEO of the Norman Rockwell Museum, during a recent press tour of the exhibition.

“During recent eras of American society, MAD magazine was a crucial venue for cultural commentary and ‘norm’-busting humor delivered predominantly through visual media. It was so popular, yet controversial in nature, that its overall impact, together, af rmed the profound potency of illustration and visual communication.”

UNFOLDS CHRONOLOGICALLY

The story of MAD is told in chronological order, with each gallery showcasing the story of a particular era of the magazine.

MAD began its life, in 1952, as a comic book, as publications of its stature did at the time. Most assume its transition, from comic to magazine, was made to avoid the heavy hand of the Comics Code Authority — an overreaching organization tasked with keeping America’s youth safe from the corruptive content of horror/true crime/anti-establishment humor comics ooding newsstands.

But as those in the know will tell you, its conversion from comic book to magazine, with issue No. 24 in 1955, had nothing to do with the impending arrival of the Comics Code Authority and more to do with Publisher William Gaines placating then-editor, Harvey Kurtzman, who wanted to make the leap from comic to an illustrated magazine targeting an adult audience. Kurtzman had just received a lucrative offer from another publication, and Gaines wished to keep his editor. MAD, thanks to Kurtzman’s demands, made the switch and avoided being put out of business by the Comics Code Authority.

Kurtzman ultimately left MAD in 1956, accepting Hugh Hefner’s offer to run Trump, a glossy, high-end satirical illustrated magazine. It folded after two issues due to the cost of production — Kurtzman reportedly spent $100,000 on the inaugural issues.

Kurtzman’s move would usher in the era of Al Feldstein, the editor who created the version of MAD magazine that the public came to know and love.

“It was really Feldstein who created MAD magazine the way most people think of it, with Mort Drucker, with Spy vs. Spy, with the fold-in, with Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions, with Don Martin. All of these talents came in under Feldstein, but whenever [the press] wrote an article about MAD, Kurtzman got all the credit,” said John Ficarra, editor of MAD from 1985 to 2018, who was on hand for the press tour.

With an advisory board led by Sam Viviano, art director of MAD magazine from 1999 to December 2017, and packed with the “Usual Gang” (along with a few other notable illustrators) — David Apatoff, Scott Bakal, Dick DeBartolo, Ficarra, Emily Suzanne Flake, William H. Foster III, Keith Knight, Peter Kuper, Judith Yaross Lee, Ph.D. (author of “Seeing MAD”) and Louis Henry Mitchell — the exhibition can be considered a “de nitive history” of the magazine; a time capsule bursting at its seams.

For many viewers, the show will be a nostalgic nod to past readings — ipping through it as we tagged along behind our mothers in the grocery store; perusing pages over the shoulder of an older kid on the bus or picking it up at the comics store. For others, less familiar with the magazine, there’s an opportunity to learn how a satire magazine shaped generations of readers, challenging everything from the government to Hollywood.

A unique feature of the exhibition is its accessibility — audience members can decide whether they want to dive into the magazine’s history or just dip a toe in the well of information gathered here. One can glide through galleries and snicker at the content or stroll amongst the content, soaking in the vast amounts of knowledge and behind-the-scenes wisdom shared on the gallery labels.

In one room, you can lose yourself in movie parodies, in another, you can go down a rabbit hole of Spy vs. Spy comic stips, both from the original cartoonist, Antonio Prohias, and current illustrator Peter Kuper. Love the magazine’s signature fold-ins? You can view original artwork and use an interactive kiosk to select and “fold” past favorites. There are sections devoted to MAD’s cultural impact, including a video in which the great Fred Astaire dons an Alfred E. Neuman mask and dances as the character in a 1959 television special.

Speaking of Neuman, have you ever wanted to know more about the origin of MAD’s mascot? Did you know the magazine was sued in 1965 for copyright infringement?

There’s a whole history lesson in the center of the first gallery — Alfred E. Neuman isn’t an original idea, but an appropriated image. The question in 1965 was whether or not MAD was infringing on the 1914 copyright of the caricature known as “The Original Optimist” who bore a similar slogan of “Me-Worry?” Luckily for MAD, they had a fan in a lawyer who helped prove the grinning mascot, while bearing a striking resemblance to the “Optimist” also bore a striking resemblance to a character featured in numerous ads from the mid and late 1800s. The suit was tossed out and Neuman’s likeness declared to be in the public domain. The exhibit even has a few of those early advertisements — for theater productions and dentist of ces — on display.

Rockwell and MAD

It may surprise some Rockwell fans that the illustrator, best known for his Saturday Evening Post covers, once considered painting the “de nitive portrait” of Alfred E. Neuman. Although never a contributor to the magazine, Rockwell considered and initially accepted a 1964 invitation from Feldstein and Art Director John Putnam to create a charcoal portrait of “MAD’s trademark boy” for $1,000. Putnam, like Rockwell, was a resident of Stockbridge, and made a call to his all-American neighbor. Recently discovered letters, between MAD and Rockwell, both in the museum archive and a private collection, con rm that Rockwell initially agreed to the deal.

But after initially agreeing, a letter from Rockwell to Putnam, just a day later, shows him stepping back: “I’m scared. I think I better back out of this one. After talking with you, and my wife who has a lot more sense than I have, I feel that making a more realistic de nitive portrait just wouldn’t do. I hate to be a quitter, but I’m afraid we would all get in a mess.”

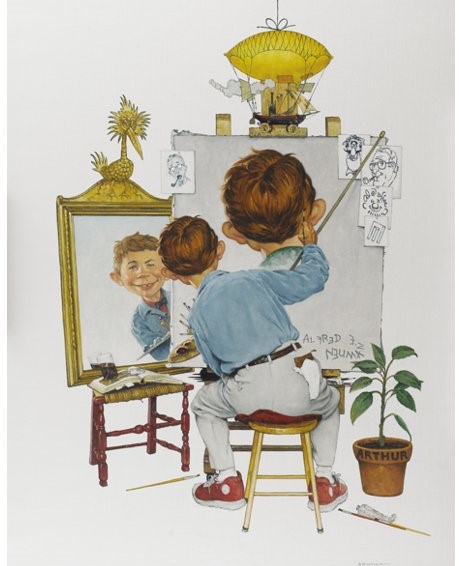

At the time, Rockwell had just left his position at the Saturday Evening Post and was taking on more serious pieces with Look magazine. But that isn’t the only time MAD crossed paths with Rockwell, as the magazine periodically parodied the illustrator’s work. On view are two parodies by MAD illustrator Richard Williams’ “Alfred E. Neuman and Norman Rockwell, 2002,” a take on Rockwell’s “Triple Self Portrait,” and “If Norman Rockwell Depicted the 21st Century — ‘The Marriage License,’ 2004” which is displayed next to Rockwell’s “Marriage Licence, 1955.”

Williams’ “Marriage License,” which features a gay couple applying for a marriage license, was published in MAD issue No. 438, February 2004, three months before the Massachusetts became the rst state to legalize same-sex marriage on May 17, 2004. Gay marriage did not become legal in all 50 states until the 2015 U.S. Supreme Court ruling.

It’s a prime example of what this exhibition does best — remind us how MAD had its thumb on the pulse of the American cultural zeitgeist for over five decades, skewering presidents, politicians and pop princesses alike. It’s a pity that it no longer graces newstands.

By Jennifer Huberdeau