BOSTON GLOBE ART REVIEW: Hilary Knight/Eloise & More

Globe Arts Writer Cate McQuaid offers high praise for NRM’s “enchanting” exhibition saying “The works are practically musical: percussive, elegant, wry.”

At Norman Rockwell Museum, ‘Eloise and More’ is an enchanting look at the artist who drew her

The show explores Hilary Knight’s life and legacy, from children’s books to Broadway posters and more

By Cate McQuaid Globe Correspondent,Updated December 27, 2022, 6:18 p.m.

ARTICLE: BOSTONGLOBE.COM

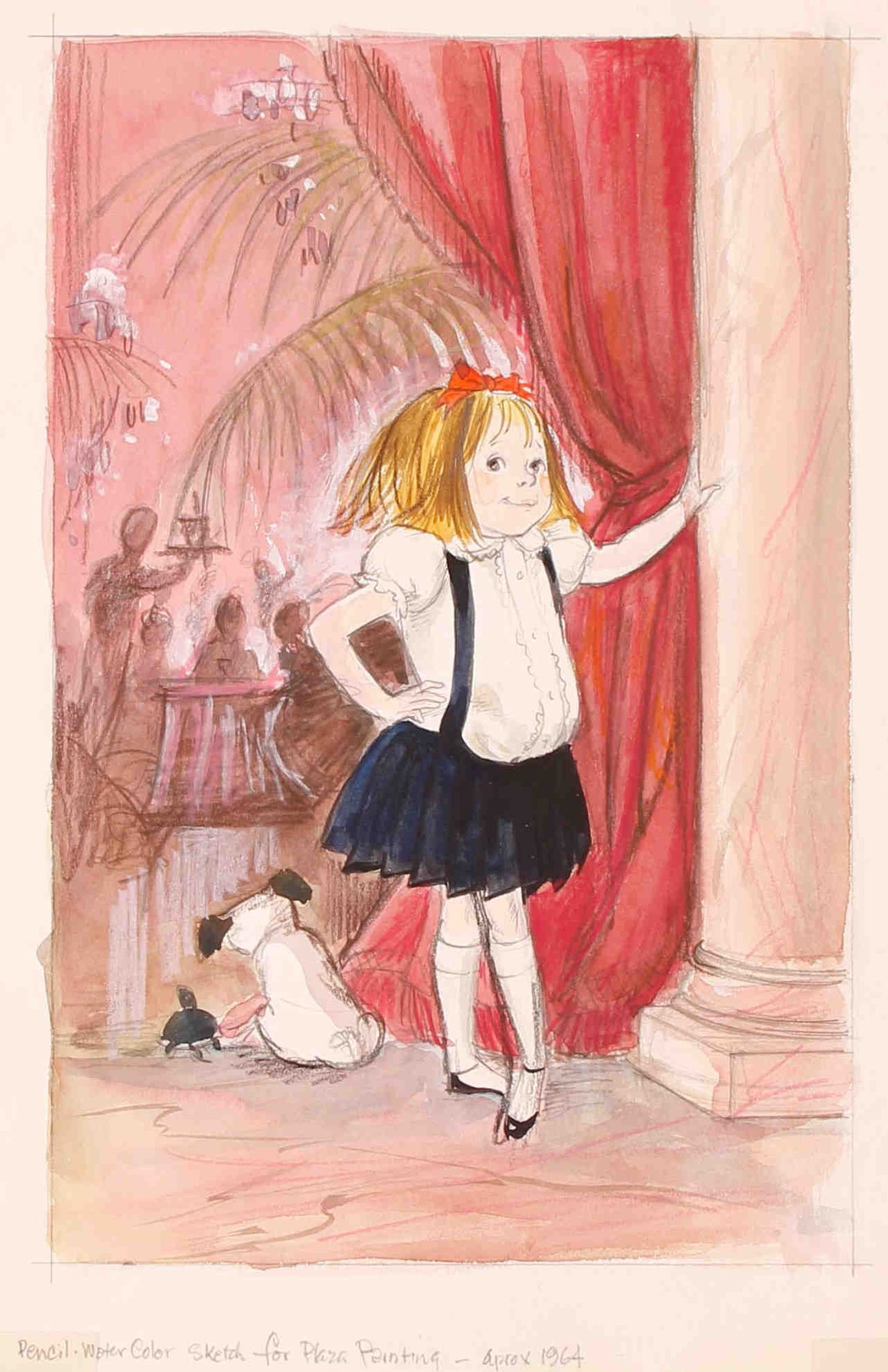

Hilary Knight, design sketch of Eloise poses for the Plaza Hotel, 1999. Collection of the artist.

© HILARY KNIGHT. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. COURTESY NORMAN ROCKWELL MUSEUM

STOCKBRIDGE — Blame the drunken debutantes.

That’s what Kay Thompson, the irrepressible author of an irrepressible character, 6-year-old Eloise, resident of Manhattan’s Plaza Hotel, told illustrator and Eloise co-creator Hilary Knight after the Eloise portrait he had given her went missing from the hotel during a Junior League Ball in November 1960.

A study for the portrait hangs in “Eloise and More: The Life and Art of Hilary Knight,” an enchanting exploration of the artist’s oeuvre, from children’s books to Broadway posters to fashion designs, at the Norman Rockwell Museum. The show is curated by Jesse Kowalski.

While there are no drunken debutantes depicted, they would be typical characters in the worlds Knight draws: at once refined and madcap, feminine and feisty. His images are a dream of New York reminiscent of 1930s-era films starring Myrna Loy, Carole Lombard, and Jean Harlow.

Knight, now 96, moved from Roslyn, on Long Island, to Manhattan when he was 6, and grew up with movies starring those bombshells. His parents, Clayton Knight and Katharine Sturges Knight, were artists, and Sturges Knight’s “Portrait of a Young Girl” hung in the family’s home. Knight has called it an inspiration for Eloise. Both girls, dressed in black, white, and rich pink, have an impertinent vigor.

Katharine Sturges Knight, “Portrait of a Young Girl.” © HILARY KNIGHT. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. COURTESY NORMAN ROCKWELL MUSEUM

But Sturges Knight’s girl stands primly still, while Eloise — as fans of the books know —is kinetic, wiry, bouncing off the page. She is a force. The poor little rich girl lives in thePlaza with her British nanny, her pug Weenie, and her turtle Skipperdee. Her parents are absent, although her mother sends emissaries and lets Eloise charge up a storm. Indeed,Eloise does whatever she pleases — often to the consternation of the hotel staff.

“Eloise: A Book for Precocious Grown-Ups” came out in 1955 — a time when independent-minded girls were not broadly depicted in popular culture. The book was a bestseller, and three more books followed before the end of that decade: “Eloise in Paris,”“Eloise at Christmastime,” and “Eloise in Moscow.”

Hilary Knight, “Sketch for Plaza Painting (Eloise),” 1964.

© HILARY KNIGHT. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. COURTESY NORMAN ROCKWELL MUSEUM

In many ways she originated with Thompson, who was herself a character: actress, gadabout, cabaret performer, vocal coach, early adapter of women’s slacks. Her biographer, Sam Irvin, has said Eloise started out as Thompson’s imaginary childhood friend. But Knight, who was a young illustrator when their partnership began, had already drawn a few audacious girls himself, on view here.

Their partnership was closer than many authors and illustrators. “It was highly collaborative,” said the museum’s chief curator, Stephanie Haboush Plunkett, in an interview with the Globe. To work on “Eloise in Paris,” she said, “He flew to Paris. She’d write lines, and he’d illustrate them. They really had a different kind of connection.”

Knight, who still draws, has a sure, playful hand. The works are practically musical:percussive, elegant, wry. A single tilted line for Eloise’s mouth conveys her slyness. If Thompson gave her unfettered certainty and imagination, Knight imbued her with propulsive electricity.

Hilary Knight, cover concept art for Kay Thompson’s “Eloise,” 1954.

© HILARY KNIGHT. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. COURTESY NORMAN ROCKWELL MUSEUM

In the mid 1960s, the mercurial Thompson removed the Eloise sequels from print,according to a wall label at the museum. It wasn’t until after Thompson’s 1998 death thatKnight returned to Eloise, publishing “Eloise Takes a Bawth” in 2002.

But his career never flagged, and his confident line and crisp compositions carry viewers through this show. In addition to Eloise books and merchandising designs, he illustrated other books, such as Betty MacDonald’s “Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle” series, and worked for magazines. He wandered New York chronicling the social scene for Vanity Fair in “HilaryKnight’s Sketchbook,” drawing hot spots such as Bill’s Gay Nineties.

Hilary Knight, “Drawn from Life,” 2017. A self-portrait celebrating Knight’s memoir.

© HILARY KNIGHT. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.COURTESY NORMAN ROCKWELL MUSEUM

Don Bacigalupi, the Norman Rockwell Museum’s former director, visited Knight in hisManhattan apartment in 2018. “Every inch of his small but glamorous apartment was decorated in high style. Walls were hung thickly with his own art as well as those by his artist parents,” writes Bacigalupi in wall text. “. . . Shelves groaned under the weight of his voluminous libraries — bound volumes of his beloved films, musicals, and theatrical recordings.”

Plunkett, who has also visited, said the artist has sheafs of studies, revealing his designer’s mind at work. Several posters for musicals including “No, No, Nanette” andthe film version of “Mame,” which starred Lucille Ball in the title role, chart his experiments with palette, composition, and style. In a Broadway poster for “Irene,” he wraps prancing star Debbie Reynolds in starry gossamer; he does the same for her successor, Jane Powell. Where Reynolds’s portrayal is a dazzling “Ta-da!,” Powell looks more like Tinkerbell ready to grant a wish.

Hilary Knight, poster study for the film adaptation of “Mame,” starring Lucille Ball, circa 1973.

© HILARY KNIGHT. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. COURTESY NORMAN ROCKWELL MUSEUM

Drawing appears to be as much life’s blood as livelihood for Knight. One wall here is covered with his sleek, fashion illustrations, made for his own delight. The inspiration: Hollywood designer Adrian’s confections for the 1936 film, “The Great Ziegfeld” (starring Loy), and other costumes from the Golden Age of Hollywood.

Knight’s imagination is lit by glamour, as well as the pluck of girls and women like Eloise and Thompson, like Mame, and perhaps even like some inebriated socialites stealing a painting on a lark. If that particular world of New York panache is mostly gone now, we’re lucky to have Knight’s imagination and his drawings. And heaven knows, Eloise Will live on, forever 6 years old.

ELOISE AND MORE: The Life and Art of Hilary Knight

At Norman Rockwell Museum, 9 Glendale Road, Stockbridge, through March 12. 413-298-4100. www.nrm.org

Cate McQuaid can be reached at catemcquaid@gmail.com. Follow her on Twitter @cmcq.

©2022 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC