Norman Rockwell: Cover Artist

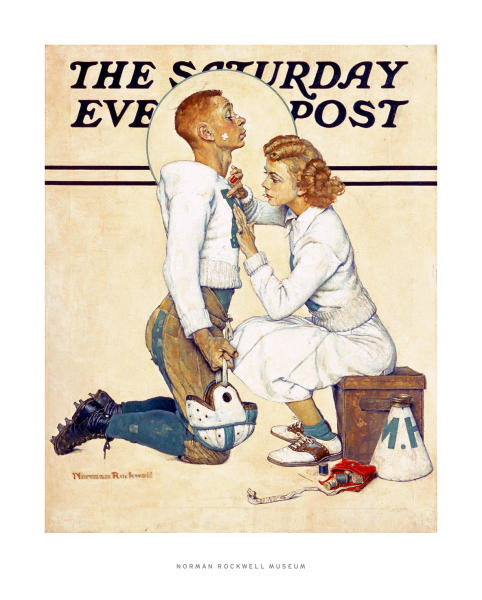

Dreaming up ideas for magazine covers and putting them to canvas was Norman Rockwell’s true passion. Although he painted Boy Scout calendars for most of his life, in addition to countless advertisements and story illustrations, magazine cover assignments gave Rockwell the freedom to create images that have come to symbolize American life in the early twentieth century.

Biographer Deborah Solomon noted, “Magazine covers were his priority and his great love. Ads and calendars would always be the part of his career that he liked least. Unlike his magazine covers, for which he usually generated his own story ideas and presided over their progress from roughs to charcoal layouts to framed paintings, ad agencies furnished him with ready-made ideas and expected him to illustrate them to specification. For this reason, he believed his Post covers had creative integrity and the potential for some kind of greatness, while diminishing his ads as hack work undertaken strictly for the money….Rockwell put magazine covers on a higher creative plane and staked his career on them.”

Even as a young illustrator, Rockwell attracted the attention of publishers. By the age of nineteen, his first cover art appeared on the September 1913 issue of Boys’ Life magazine, and as the publication’s art director, he helped to shape the direction of the periodical in its early years, Rockwell illustrated scores of paintings and drawings that appeared on the covers and pages of American Boy, Boys’ Life, St. Nicholas, Youth’s Companion, The Country Gentleman, American Magazine, Ladies’ Home Journal, and The Saturday Evening Post.

In a thoughtful summation of Rockwell’s forty-seven-year career at the Post, New York Times art critic David L. Shirey reported on a 1972 retrospective exhibition of the artist’s paintings at the Brooklyn Museum of Art. He noted…

“One has to smile at the embarrassing situations that the artist’s characters get caught up in and at the common human foibles we are all subject to. Mr. Rockwell creates an Eden for us. It may be nonexistent, but it offers a temporary refuge from reality. He never shows us the sad and somber side of life. If there is unhappiness in his work, it lasts for but a moment.” – David L. Shirey

In the 1960s, Rockwell turned his attention to more serious social concerns, having secured his reputation as a trusted visual commentator.

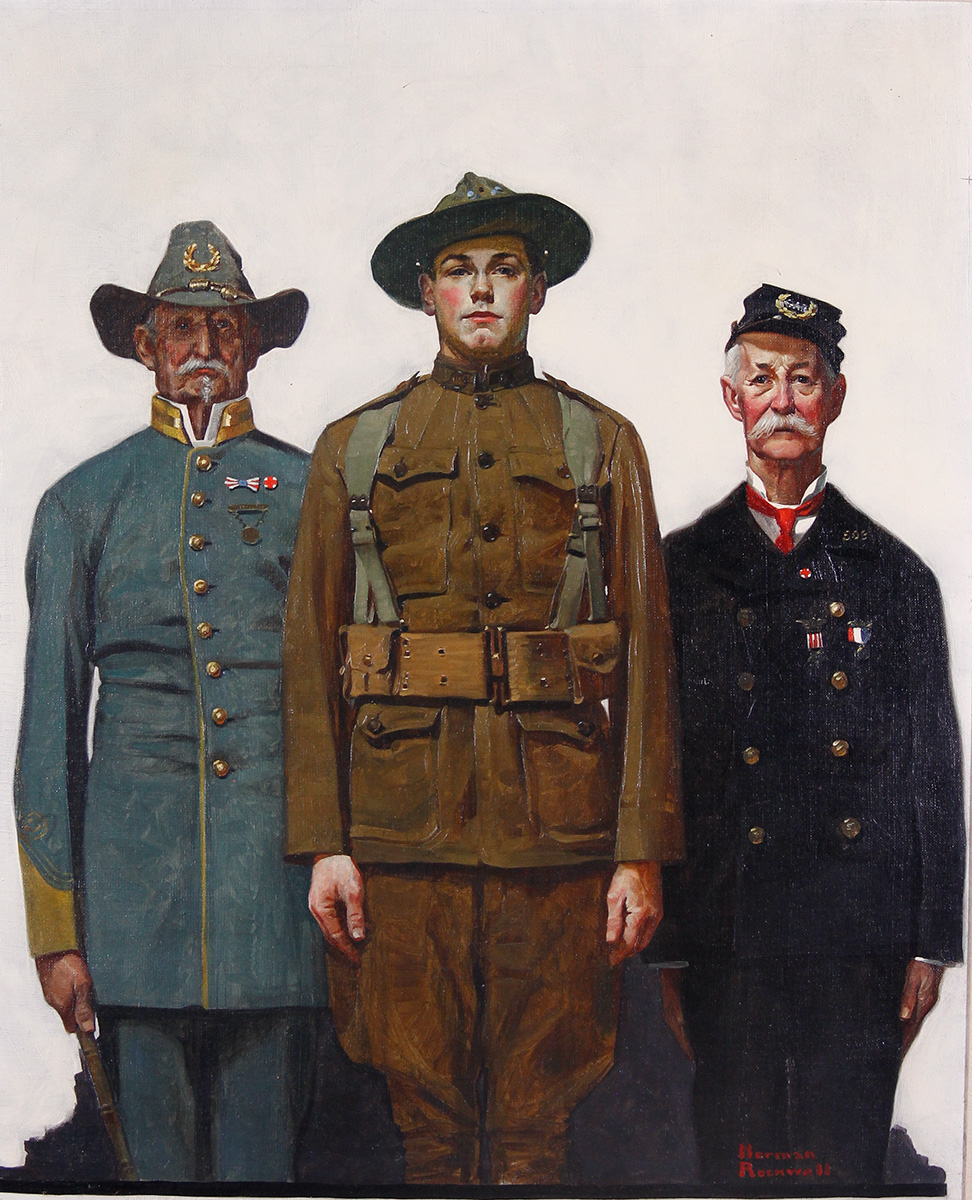

Though he had painted over a dozen magazine covers by 1916, this illustration was Rockwell’s very first Post cover, for which he was paid $75. He wrote, “In those days the cover of the Post was the greatest show window in America for an illustrator. If you did a cover for the Post you had arrived. . . . Two million subscribers and then their wives, sons, daughters, aunts, uncles, friends. Wow! All looking at my cover.”

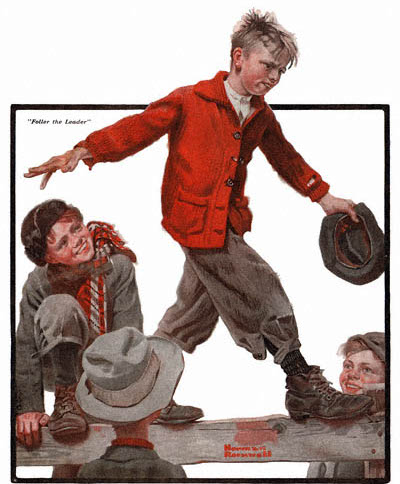

Though humorous in nature, this is one of many covers where Rockwell featured children in a way that reflected a serious shift in the societal view of masculinity, frequently discussed in the national press. Many in the middle-class feared a general feminization of American life and culture. The anxiety was prompted by a series of social, cultural, and economic developments that challenged traditional masculine authority. The closing of the frontier, the women’s movement, and the growth of urban, corporate life, for example, were perceived as threats to patriarchal power. Billy Payne, a frequent model in Rockwell’s early paintings, appeared on the cover as the model for all three boys.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

“The commonplaces of America are to me the richest subjects in art.”

⸺Norman Rockwell

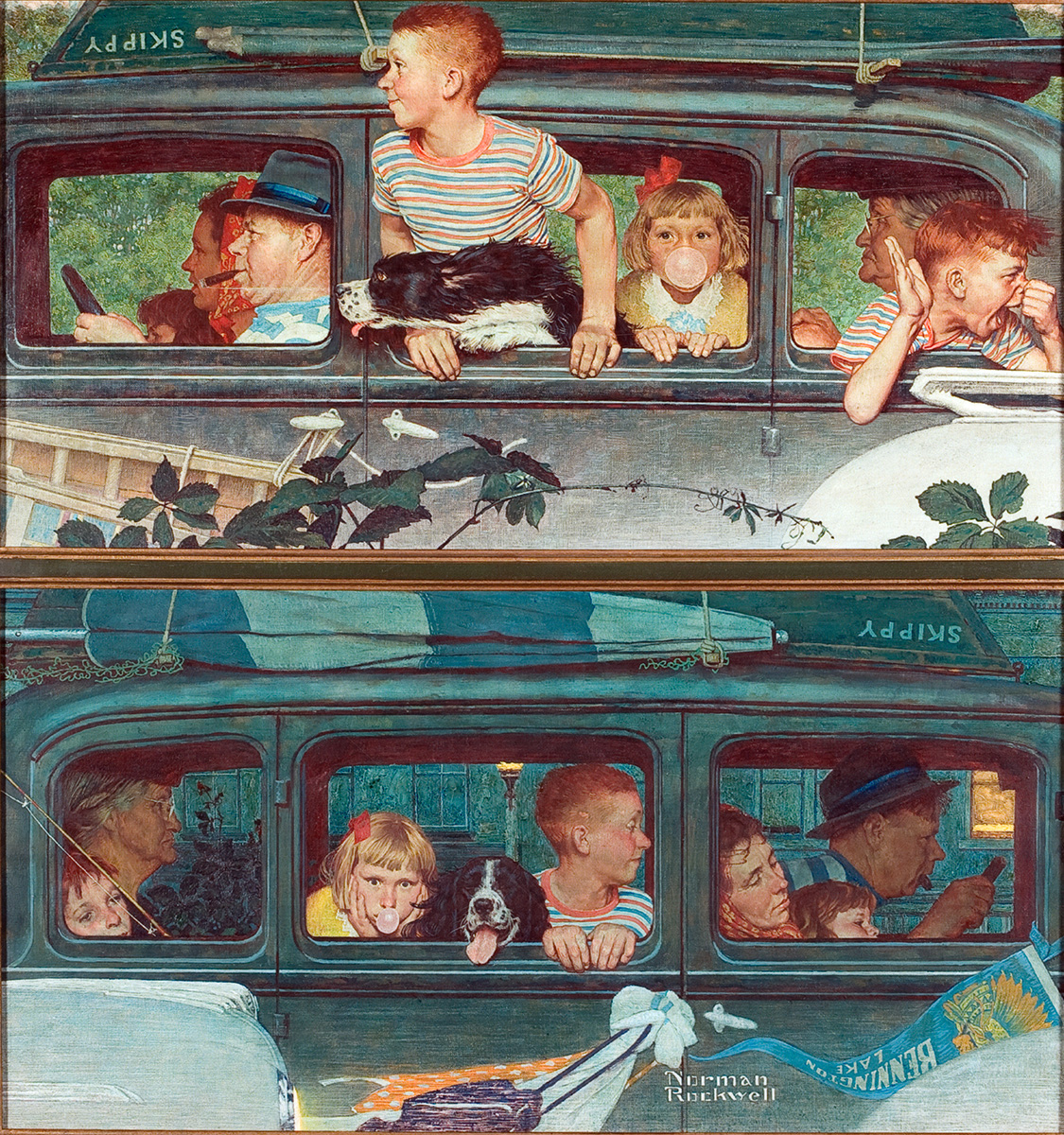

Among Norman Rockwell’s best-known illustrations are heartwarming scenes that capture the essence of American holiday traditions celebrated throughout the year⸺from Valentine’s Day and Independence Day to Halloween, Thanksgiving, and the magic of the Christmas season.

Rockwell’s connection to holiday-inspired art can be traced to his youth, when at the age of fifteen, a parishioner of his family’s church employed his talents for Christmas card designs. As an adult, Rockwell would work with Hallmark, a company that continues to market his midcentury illustrations for holiday greeting cards. The Saturday Evening Post, which showcased his art for forty-seven years, typically delegated Christmas, Thanksgiving, and New Year’s covers to its most popular illustrators. During Rockwell’s first year with the magazine in 1916, his work was featured on a December cover, and subsequently, the front pages of many additional holiday issues were assigned to him. Seasonal rituals and snowy New England landscapes are viewed through the eyes of homecoming veterans and cheerful, intergenerational families who inhabit Rockwell’s artworks.

Throughout his career, Rockwell considered a strong visual story concept was “the first thing and the last,” no matter the subject. He often told reporters that despite his unending work schedule, he indulged himself by taking a half-day off on Christmas. Though he used his own art to embellish seasonal cards for friends and family, he was not overly sentimental about the holidays. He viewed turkey carving as “a challenge rather than an invitation,” and he once remarked, “I’ve never played Santa Claus in my life. I wouldn’t dare to.” Holiday festivities were prominently featured in Rockwell’s work, and inspired readers to consider how their own experiences reflected, or stood in contrast, to those portrayed in his art. Many of Rockwell’s beloved seasonal images are on view.

IMAGES

RELATED EVENTS

MEDIA

VENUE(S)

Norman Rockwell Museum, 9 Glendale Road, Stockbridge, MA 01262

DIRECTIONS

Norman Rockwell Museum

9 Glendale Road Route 183

Stockbridge, MA 01262

413-931-2221

Download a Printable version of Driving Directions (acrobat PDF).

Important note: Many GPS and online maps do not accurately place Norman Rockwell Museum*. Please use the directions provided here and this map image for reference. Google Maps & Directions are correct! http://maps.google.com/

* Please help us inform the mapping service companies that incorrectly locate the Museum; let your GPS or online provider know and/or advise our Visitor Services office which source provided faulty directions.