REVIEW: Representation matters: Race and perception are center stage in ‘Imprinted: Illustrating Race’ at the Norman Rockwell Museum

July 1, 2022

Plan your visit to see IMPRINTED: Illustrating Race and IN OUR LIFETIME today.

Read Full Article: The Berkshire Eagle

STOCKBRIDGE — The advertisement seems harmless. A cherub faced toddler, rosy-cheeks, a paper hat upon his head and bayonet slung over his shoulder gazes up lovingly at a chef clad all in white save for his red bow tie. The chef, with a serving tray topped with a piping-hot bowl of porridge, stares out at the viewer — an amiable grin on his face.

But the advertisement, “His Bodyguard,” is not as innocent as it seems. For over a century, “Rastus,” as the chef was named, was the congenial Black mascot of Cream of Wheat. In marketing campaigns, the chef, was often surrounded by white children, lovingly staring at him, or rather the bowl of Cream of Wheat.

Look past the wide grin of Rastus or any of his trademark associates — Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben or Mia the Land O’Lakes “butter maiden” — and you’ll find a history steeped in systemic racism. Just the chef’s name is problematic; Rastus is a coded word — a stereotypical, derogatory name used since at least 1880 — for docile, non-threatening Black men. But even more problematic is the imagery of the marketing campaigns; repetitious depictions of Black and indigenous men, women and children subservient to the white people around them.

The mascots are gone now, “retired” in 2020. (Not without a fight, and only after Black Lives Matter protesters challenged the imagery.)

Why did it take so long?

That’s the question “Imprinted: Illustrating Race,” on view at the Norman Rockwell Museum through the end of October, answers in a sprawling exhibit that covers 400 years of illustrated history with some 300 artworks and objects.

Simply put, the answer is one of access and power; those who have it are the gatekeepers and decide what we see and hear, what messages we are inundated with, consciously and unconsciously. But of course, the explanation is much more complicated.

To start, you have to begin at the beginning, both of American illustration and of the exhibit, which began with the decade-long research of co-curator Robyn Phillips-Pendleton, an illustrator and professor of visual communications at the University of Delaware.

“It’s important to me, as a Black illustrator, to know why we get the jobs that we get. And why aren’t there more illustrators of color? Because I make images, it was very interesting to me to take this journey, to follow the images. Who hires the illustrators? And who has the power to decide what kind of images are made and not made? In what rooms are these decisions being made?,” Phillips-Pendleton said during a recent interview at the Norman Rockwell Museum.

“Images were created before photography and that makes them as strong as photographs. So, I followed the images in my research. I didn’t write or follow the history, I followed the images themselves and where they led me. I also followed the images through different platforms — as 3-dimensional objects including periodicals through Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and Harper’s Weekly.”

What Phillips-Pendleton and co-curator Stephanie Haboush-Plunkett, deputy director and chief curator at the Norman Rockwell Museum, have put together is not easy to digest, nor should it be.

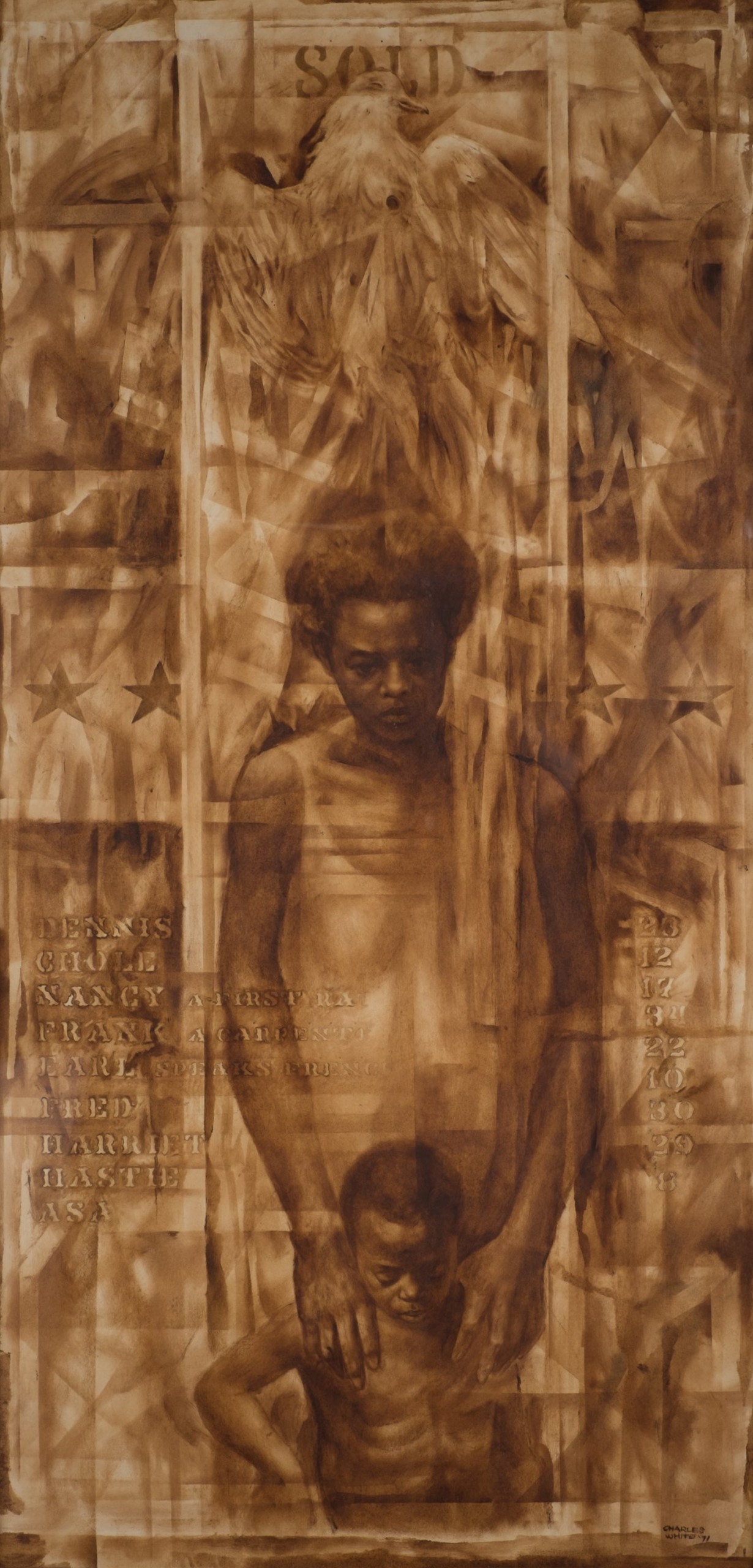

Early in the show, viewers are presented with images and illustrations that have established long-lasting attitudes toward race. There are images of enslaved men being sold that were used interchangeably by both abolitionists and pro-slavery publications. Images of Native Americans that designed to showcase their “exotic” nature adorn souvenir plates and hock tobacco. There are images of the “noble indian” and “the savage.” There are enslaved men rushing to the aid of their masters on the battlefields of the Civil War.

Then the images change after emancipation, Black men and women are depicted as either loyal, subservient workers or lazy, sly, shifty criminals and jezebels. Advertisements for minstrels, with white men in black-painted faces, hang side-by-side with advertisements for Cream of Wheat, Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben’s Rice and the lesser known C–n Chicken Inn. There are derogatory images of Asians, with buck teeth and braids, working hard and eliminating jobs of white workers.

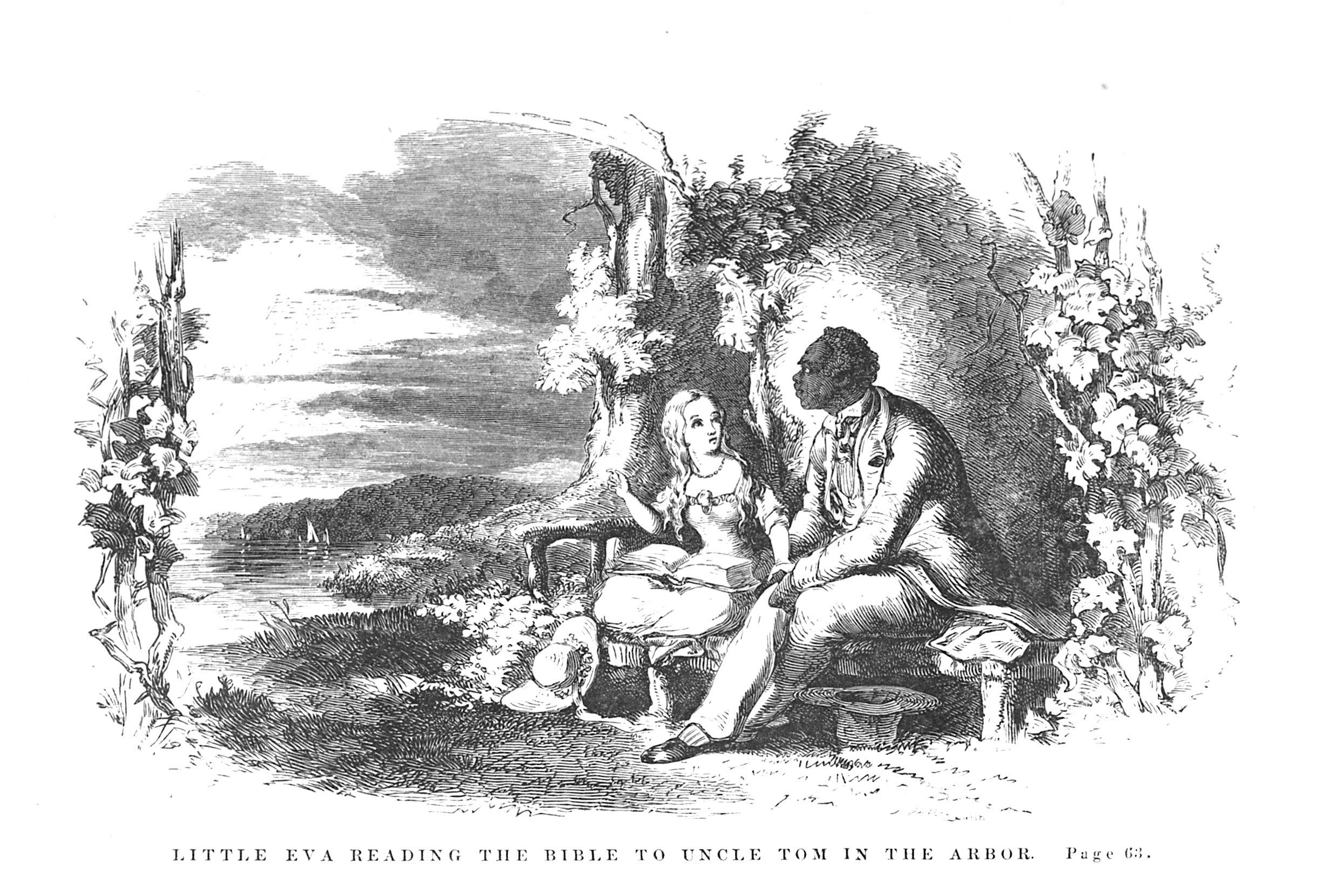

The gatekeepers, we’re reminded, hold the keys to what we see. An illustrator could create one image, but that didn’t mean it stayed that way after it traveled through the hands of others. Such is the case of illustrations of different versions of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” On display are the six images Harriet Beecher Stowe commissioned for her abolitionist novel, by Hammatt Billings, including one of Little Eva teaching Uncle Tom to read in the arbor. Eva appears with Tom who is in his early 40s. Juxtaposed are illustrations for a British edition of the book by George Cruikshank, a British artist who worked in America, which are very different. Eva is still a child, while Uncle Tom is now grandfatherly — a more acceptable relationship and age distance.

“Cruikshank created 21 additional scenes. He was known for caricatures and more of a comic style. In his interpretation of the story — which was happening at the same time, 1851 to 1852 [as Stowe’s original] — he embellished. He added violence. He added a lot of things to the story that was not in the original intent of the story of the abolitionist novel,” Phillips-Pendleton said.

A RENAISSANCE IN HARLEM

But for all the hatred in this narrative, there is hope. Once again we are reminded that the gatekeepers hold the keys, as the Harlem Renaissance arrives. Black artists, musicians and writers emerge, as does the Black press. Black authors and illustrators grab hold of the narrative and create images of Black people that are true to who they are, not as they are seen or depicted.

It was during the Harlem Renaissance that magazines like the The Messenger, Fire!, the NAACP’s The Crisis and the National Urban League’s Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life came into existence. The magazines, published by Black publishing houses and editors, featured images, illustrations and literature from Black artists.

“The periodical was very important because these were magazines that were circulating around the home. Black families moved during the Reconstruction period, so they were circulating all across the United States,” said Cherene Sherrard-Johnson, professor and chair of English at Pomona College and an advisor of the exhibit. “This was a way of changing the image, moving away from the plantation stereotypes to this new modern subject.

“This especially happened after [WWI]. One of the arguments for why the Harlem Renaissance happened was because you had these servicemen who had fought overseas and were treated like full human beings, who were returning home from the war and coming back with a renewed sense of self and that culminated in an interest in Black art. Patrons finally put money behind Black artists, Black writers and that’s really the renaissance you see that was reflected in the art and visual culture and literature of the era. And of course what happened was the escalation of violence in response to this idea of men and women having pride and really demanding these rights that they deserved as Americans.”

REVOLUTION AND EVOLUTION

Although the Harlem Renaissance was short lived, cut short by another word war, it had sparked a revolution; a need for representation on all levels. In the following decades, Black artists and writers would continue to turn out works for Black publications and begin breaking into mainstream media outlets.

And when the major publications didn’t carry their work or news, Black publishers filled the void. One prominent voice was the Black Panther Party Newspaper that ran from 1967 to 1980.

“The Black Panthers were started in 1966 in Oakland, Calif., to combat rampant police brutality in their neighborhoods. In 1966, Ronald Reagan was governor of California. There was open carry of long guns in California at that time. So when the Black Panthers started patrolling their neighborhoods with long guns, a representative named [Donald] Mulford decided to introduce legislation to control guns in California. So Ronald Reagan was in charge as California enacted gun control,” said Colette Gaiter, professor of Africana studies and Art & Design at the University of Delaware.

The Black Panthers responded by demonstrating at the California Capitol Building in May 1967, marching, with long guns, into the building. Photos of the act of protest, labeled as an “attack” or “invasion” went viral.

“It looked like they were raiding the Capitol Building. Everything they were doing was legal,” Gaiter said. “The Black Panther Party was tired of the way Black people were treated — the lack of opportunity, the lack of jobs, health care, conditions in Black communities. They decided to make noise.

“Emory Douglas was a young designer who joined the party and told them he could make their newspaper better. He began making these very bold graphics. One thing that Huey Newton and Bobby Seale decided early on was that images were a really important way to communicate ideas of liberation to Black people and the public in general. The intentions were two-fold, to empower and to motivate people.”

Other artists, such as Gayle Dickinson, one of two women working for the Black Panther Party Newspaper, presented “very slice of life drawings; what life was like in the ghettos,” Gaiter added.

“Black people were barely represented in the media in the 1960s, but as servants in these stereotypical roles or they were people depicted in something sensational such as crime. But there was no everyday life. So that was one of the things that was so important about the Black Panther newspaper, it showed what everyday life was like for Black people,” she said.

REPRESENTATION MATTERS

Perhaps the most important work in the exhibition is that of present day illustrators, who are ensuring that contemporary literature and art is populated with positive images that correctly represent Black society.

Here are works of Phillips-Pendleton, Rudy Gutierrez, Gregory Christie, the late Jerry Pinkney (Norman Rockwell Museum Artist Laureate), Robert Cunningham, Chris Hopkins, Alex Bostic and many more. There are images of Tuskegee Airmen, Gutierrez’s flowing spiritual images of John Coltrane, Bostic’s “Lando as a boy,” a painting of Lando Calrissian as a Jedi, commissioned for “Star Wars Visions.” And there are beautiful soft images of children and boldly colored illustrations of women, engaged in acts of self care.

It is a room filled with hope and aspirations, of images from everyday life and images of incredible achievements.

“This has been a complete joy,” said Hollis King, a graphic designer, and a national advisor to the exhibit who designed the exhibit’s companion catalog. “Because, I kept thinking to myself, I wish I had a book like this when I was in art school. I wish I could have seen representation like this.

“Why does this matter? When you are pursuing a dream, something that is really difficult, when you see someone like you doing it, it reinforces it gives you hope, it gives you something to shoot for. And for a long time, we didn’t have that. I should say that as part of this project was man named Jerry Pinkney. Jerry Pinkney meant a lot to me when I was going to art school. He encouraged me late at night. I would think, if Jerry could do this, I can do that.

“On our first call [of this group] I expressed my love and appreciation [to Jerry] and of course, we did not know that would be our last conversation with Mr. Pinkney. And so, we create art. We tell our stories. We create joy. We help people who are broken. And try to understand the world through making art.

“Art is our refuge. It’s our beauty. And everybody’s story needs to be told to help lift the American story. And I think that is part of what this exhibition does. It takes the courage of good people to be a force in the world.

“We all can have a better world and a better future for our children.’’

Plan your visit to see IMPRINTED: Illustrating Race and IN OUR LIFETIME today.