The Art of Norman Rockwell: Highlights from the Permanent Collection

Norman Rockwell was one of busiest and industrious illustrators of his time. “Meeting deadlines and thinking up ideas are the scourges of an illustrator’s life,” Rockwell said. In order to satisfy the high demand for his art from publishers and advertisers, it would not have been unusual to find him in his studio seven days a week and on holidays.

A humanist and close observer of the world around him, it is perhaps no surprise that working Americans across a broad range of employment sectors were a focus of Rockwell’s art – from education, health care, and law enforcement to agriculture and essential trades. A sense of longing, desire, and humor are entwined in the artist’s wishful images of hardworking people, who seek to do their best and sometimes dream of something more. The artworks in this gallery span Rockwell’s long career, and acknowledge the dignity and dedication of the American worker as seen through his eyes.

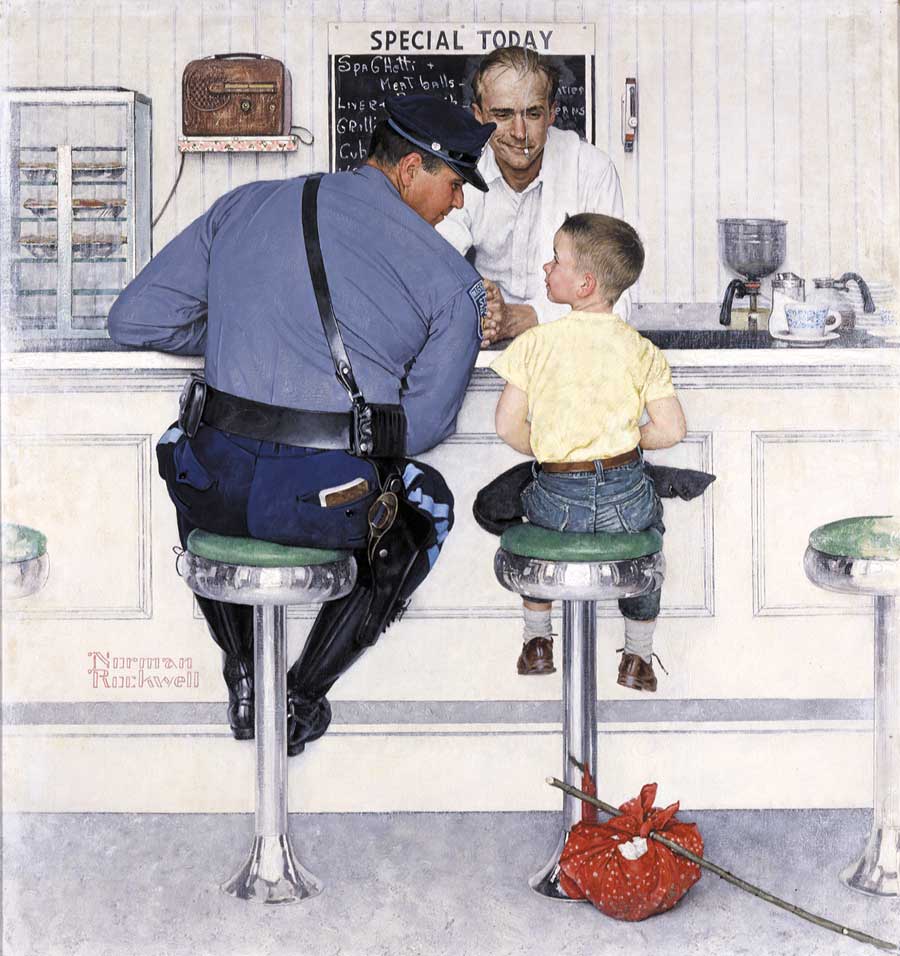

THE LUNCH COUNTER IN AMERICAN CULTURE

From the early 1900s until the 1970s, lunch counters served as gathering places for urban and small town customers who stopped in for quick meals, ice cream, carbonated beverages, and conversation. Despite America’s nostalgia for these social hubs, as memorialized in popular television shows and movies, lunch counters and soda fountains are also emblematic of the nation’s history of racial strife. Required to come in through the back door and sit in the rear if allowed entry at all, African Americans were barred from being seated or served in many establishments during the first half of the twentieth century. In the 1950s and 1960s, peaceful sit-ins were staged at popular lunch spots in many college towns to protest racial injustice. Met with a mix of anger, resistance, and support, these demonstrations became a nationwide movement to serve as a catalyst for change. Lunch counters, as portrayed in Rockwell’s hopeful illustrations, are reminiscent of the “good old days” for some, but not all.

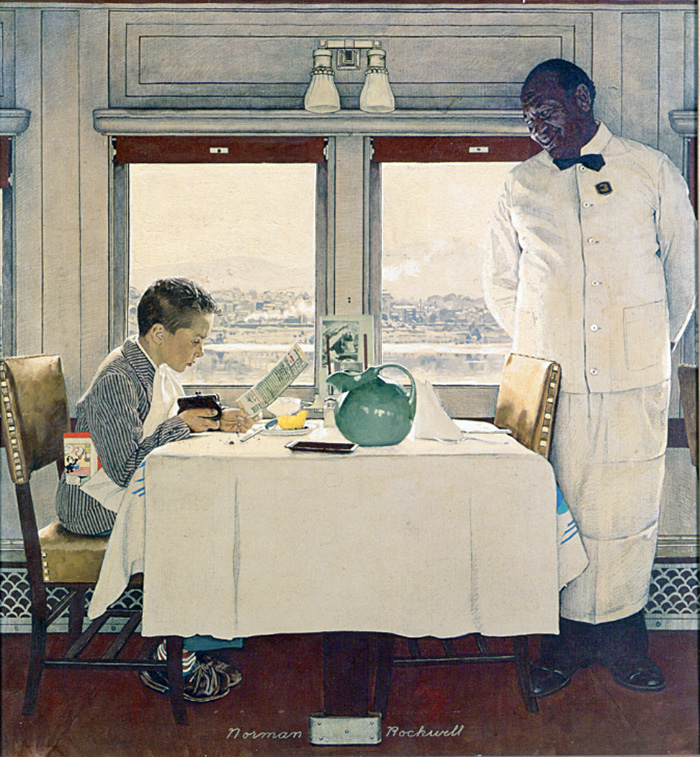

ILLUSTRATION AND RACE

Commissioned for public consumption, the art of illustration is woven into our daily lives as it has been for centuries. Perceptions of people, groups, and societal norms are derived from widely-circulated illustrated images that have appeared in printed matter and periodicals, and on today’s digital screens. Illustrators are often asked to represent group values, and in the early and mid-twentieth century, deference to those constraints provided a means of reproduction and distribution of their art. At the time, American periodicals were marketed to a largely white demographic majority and supported by an army of advertisers who greatly influenced their content. In the post-World War II years, a newly empowered buying public emerged, and until the Civil Rights Movement, African Americans and other people of color were almost completely invisible on the pages of American magazines—whether on covers, in fiction articles, or in ads. Prevailing attitudes regarding race and the representation of Black people in the Jim Crow era and beyond were reinforced in mass-circulated publications such as The Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s, and in popular women’s magazines like Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, and McCall’s, which portrayed people of color in stereotypical or subservient roles. During the 1940s and 1950s, top publications had millions of subscribers, making illustrators, art directors, and publishers prominent tastemakers who played a prominent role in affecting cultural beliefs.

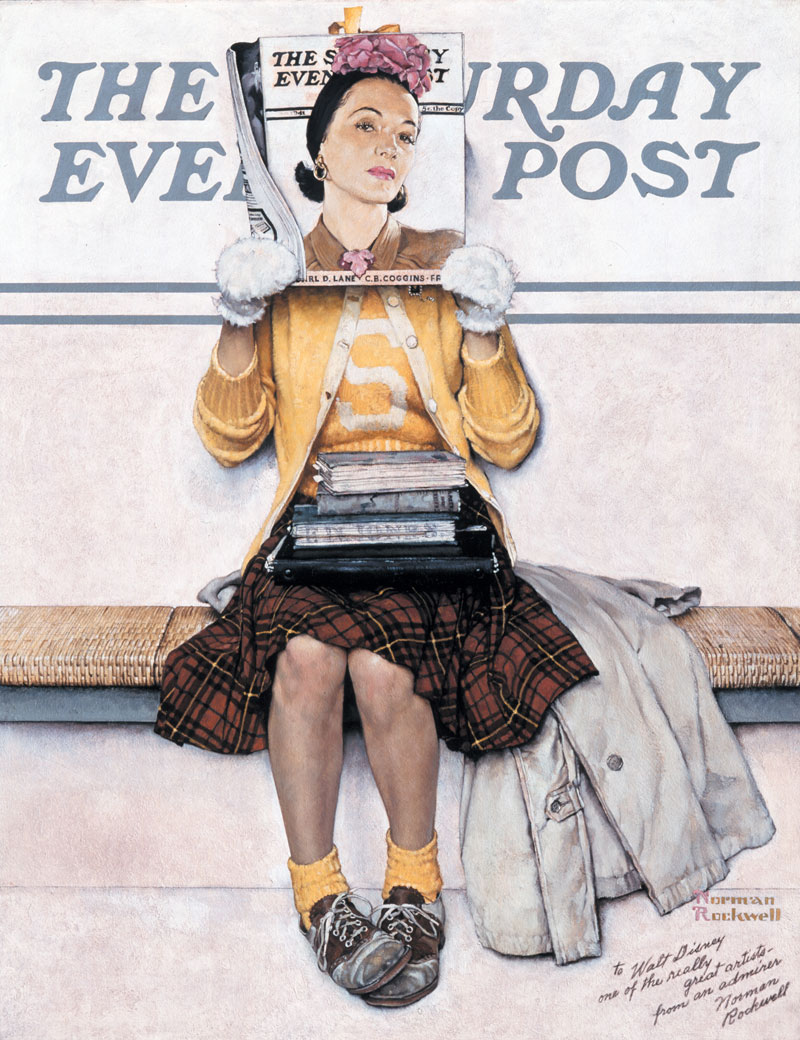

WOMEN IN THE POPULAR PRESS

In his youth, Norman Rockwell was familiar with the images of glamorous women created by popular male illustrators Charles Dana Gibson, Howard Chandler Christy, C. Coles Phillips and others for American periodicals. Busy with early commissions for children’s magazines, he mastered the art of painting the antics of boys, but his real ambition was to illustrate a cover for The Saturday Evening Post. Emulating the covers of the time, he created a Gibson-style girl being kissed by an elegant man, but when Rockwell asked cartoonist friend Clyde Forsythe for his opinion of the work, he declared it to be “Terrible. Awful. Hopeless.” He advised Rockwell to stick to what he did best – painting kids – and for some years, he took his friend’s advice.

Illustration, like photography and film, has helped to establish societal gender and appearance norms. Portrayals of women, created largely by male artists and circulated by advertisers and mass magazines, have been used to attract audiences and sell publications and products. The term “male gaze” was coined in 1976 by film critic Laura Mulvey, referring to the presentation of women from a distinctly male perspective in the visual arts and literature. Rockwell once commented that he painted “the kind of girls your mother would want you to marry,” though his female protagonists were often complex, strong, and savvy, as in the art on view.

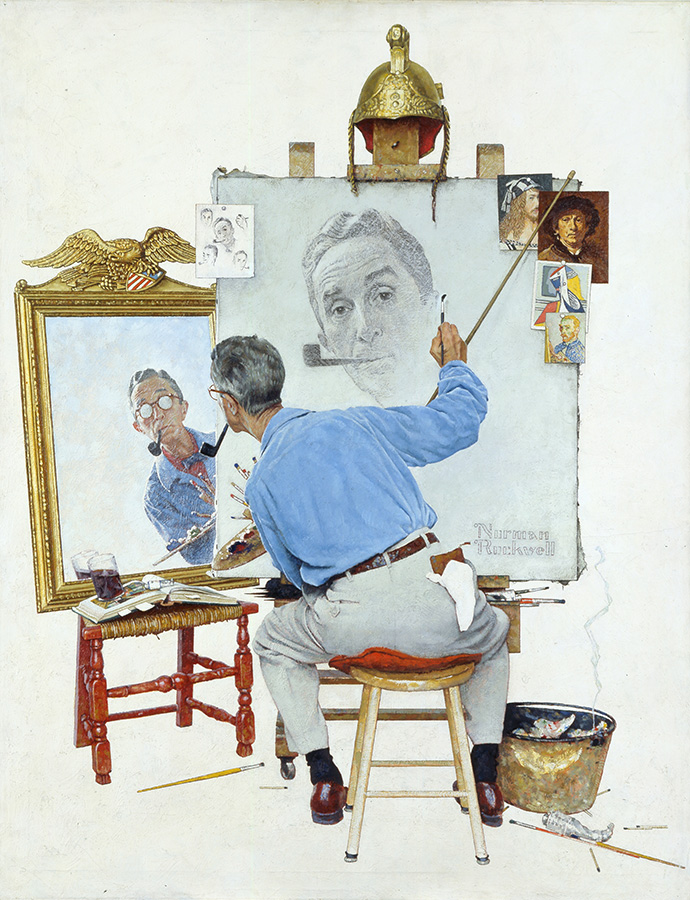

ARTISTIC IDENTITY

Norman Rockwell and his mid-century illustrator colleagues spent their careers working to enliven the pages of American magazines, but they were pushing against the tide. At the time, there was heated debate about the relative merits of abstract art, realist art, and popular illustration, and Rockwell’s brand of visual storytelling was frequently caught in the crossfire. By the late 1940s, shifts in technology—which brought the world to the masses through photography and television—and challenges by modernist art idioms, conspired to relegate conventional illustration to a lesser status. Traditional narrative illustration was a waning discipline, and though Rockwell was admired by many, he was also an institution to younger generations who viewed him as the old guard. For all of his complexity, and perhaps because of it, Rockwell became a catalyst for change for illustrators seeking to blur the lines between fine and applied art. In the works on view, Rockwell considers his place in the art world during changing times.

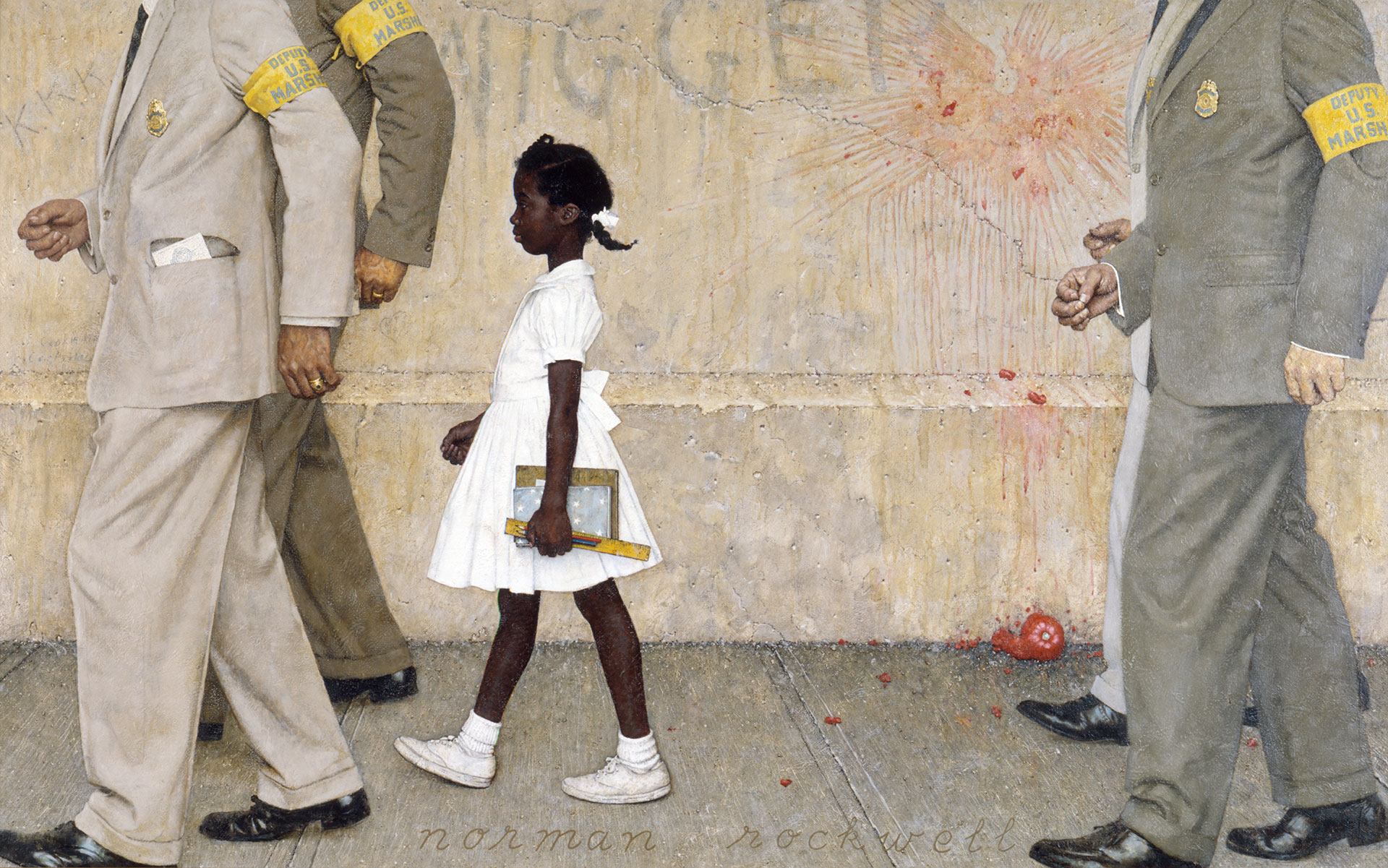

CIVIL RIGHTS AND THE POPULAR PRESS

In the 1960s, moving beyond his popular humanistic illustrations depicting the lives and experiences of white protagonists for the Post and other publications and advertisers, Rockwell sought to express his personal viewpoints through the documentation of social and humanitarian subjects. As evidenced in his Four Freedoms paintings, published in 1943, he wanted to make a difference with his art, and as a trusted and highly marketable illustrator, he had the opportunity to do so. In addition to Rockwell’s personal desire to inspire change through his work, this installation explores the publishing, cultural, and artistic trends that also inspired reconsideration of his direction.

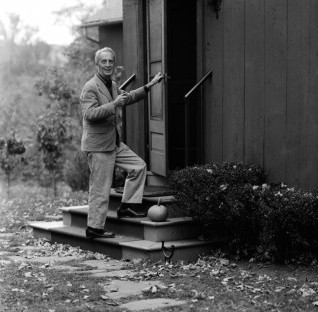

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Born in New York City in 1894, Norman Rockwell always wanted to be an artist. At age 14, Rockwell enrolled in art classes at The New York School of Art (formerly The Chase School of Art). Two years later, in 1910, he left high school to study art at The National Academy of Design. He soon transferred to The Art Students League, where he studied with Thomas Fogarty and George Bridgman. Fogarty’s instruction in illustration prepared Rockwell for his first commercial commissions. From Bridgman, Rockwell learned the technical skills on which he relied throughout his long career. Learn more…

Born in New York City in 1894, Norman Rockwell always wanted to be an artist. At age 14, Rockwell enrolled in art classes at The New York School of Art (formerly The Chase School of Art). Two years later, in 1910, he left high school to study art at The National Academy of Design. He soon transferred to The Art Students League, where he studied with Thomas Fogarty and George Bridgman. Fogarty’s instruction in illustration prepared Rockwell for his first commercial commissions. From Bridgman, Rockwell learned the technical skills on which he relied throughout his long career. Learn more…

IMAGES

MEDIA

RELATED EVENTS

VENUE(S)

Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, MA

DIRECTIONS

Norman Rockwell Museum

9 Glendale Road Route 183

Stockbridge, MA 01262

413-931-2221

Download a Printable version of Driving Directions (acrobat PDF).

Important note: Many GPS and online maps do not accurately place Norman Rockwell Museum*. Please use the directions provided here and this map image for reference. Google Maps & Directions are correct! http://maps.google.com/

* Please help us inform the mapping service companies that incorrectly locate the Museum; let your GPS or online provider know and/or advise our Visitor Services office which source provided faulty directions.