The “Contemporary” Racial Conscience and Sensitivity of Norman Rockwell

June 11, 2020 – Written By: Louis Henry Mitchell

Throughout his extremely successful career, Norman Rockwell depicted an ideal of life that resonated with the majority of the people in America. However, the minority of the people of America were also a deep consideration within Mr. Rockwell. Although challenged with certain company restrictions from The Saturday Evening Post, Norman Rockwell found a way to honor or reveal African-Americans in his work. One would think that African-American people, or any people of color, were not on Mr. Rockwell’s mind because of how rare it is to find any of them in his work for the Post. As an African-American teenager I wasn’t’ focused on that aspect of his work because I was just so enamored with his ability to bring people to life with a stick of charcoal or a paintbrush. I marveled at his technique as well as his loving and human portrayal of people doing everyday things. The fact that I only saw white people in his work didn’t dawn on me until I started hearing other people talk about it.

In my home, my mother kept my sisters and me aware of how others might treat us because of our color, but she refused to make it an issue because we might be crippled by the fear of what might happen to us. She went through horrific racism and sexism for much of her adult life, especially when she was going to nursing school in the 1930s. She almost gave up but was encouraged by her own mother to keep going and finish her education. In passing this courageous attitude to my sisters and me she also minimized race as a potential obstacle and focused on encouraging us to reach for our dreams. It’s not that we were unaware of racism, that would have been impossible back in the 1960s when I was growing up. But racism was kept from being a debilitating challenge for my sisters and I even in the face of it. So, my appreciation for Rockwell’s work was purely about how this man could make drawings and paintings that told such great stories and looked, and felt, so real. The awareness of the lack of people of color in his work became a presence in the back of my mind, but not a distraction from continuing to learn from my favorite artist.

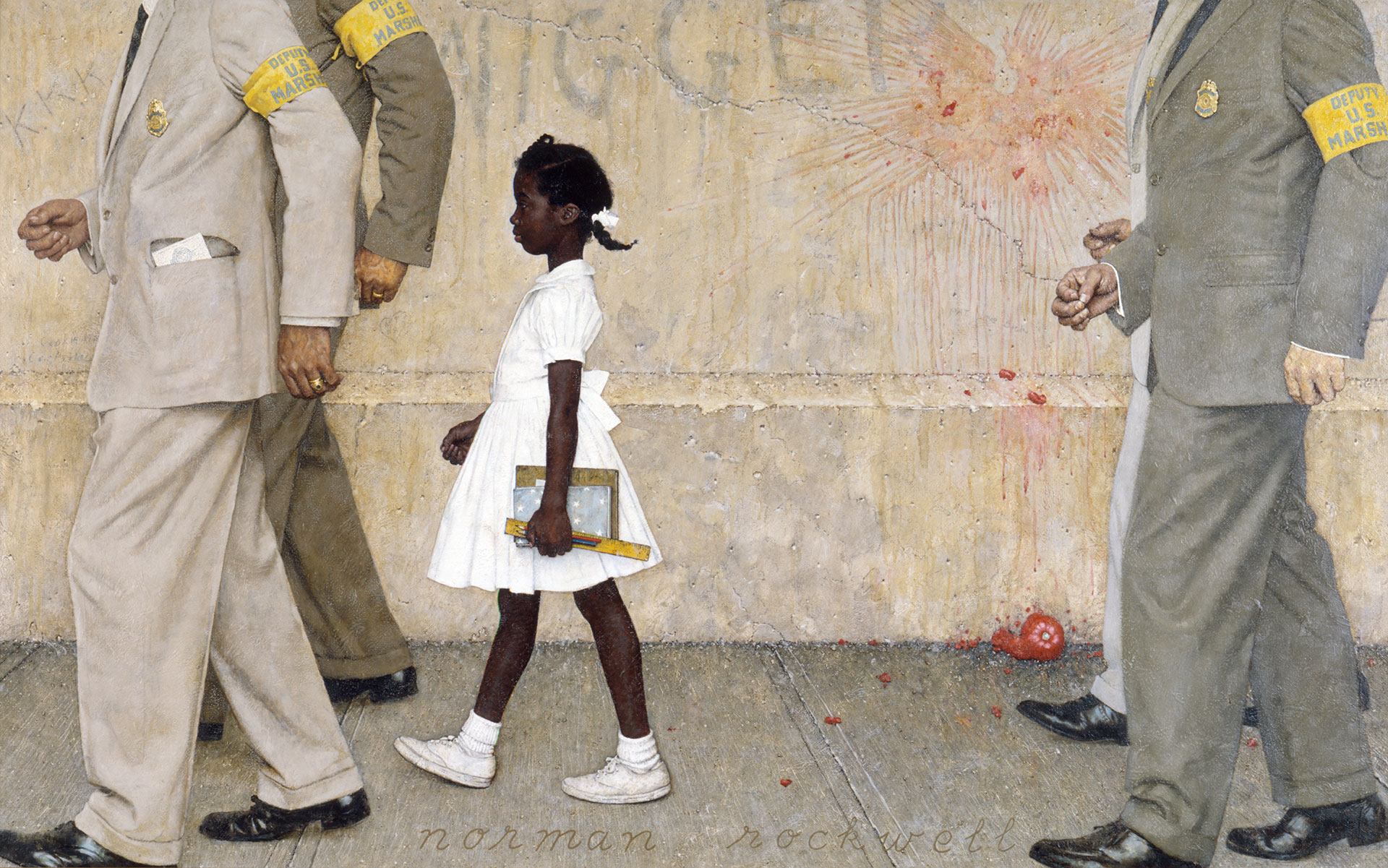

The 1960s would prove to be the opening of the floodgates of Rockwell’s love and concern for all humanity. After leaving the Post in 1963 he did one of his most famous and important paintings, “The Problem We All Live With”. This symbolized a moment in the life of Ruby Bridges at six years old being escorted by U.S. Marshalls to help end segregation in a school in the South. But it was also a depiction of a moment in the state of America that still resonates to this very day and moment. Racism is still a raging storm in our nation and it is frightening how African-Americans can still, directly, relate to that little six year old girl from 1963, even though she has grown into a mature and prominent social activist. Rockwell’s painting can almost have been done today as much as it relates to this very day and age. He was, at last, unleashed to represent African-Americans but what a striking contrast to how he had originally intended to represent them. Rockwell was told “never to show colored people except as servants”, as he revealed in a 1971 New York Times article by Richard Reeves

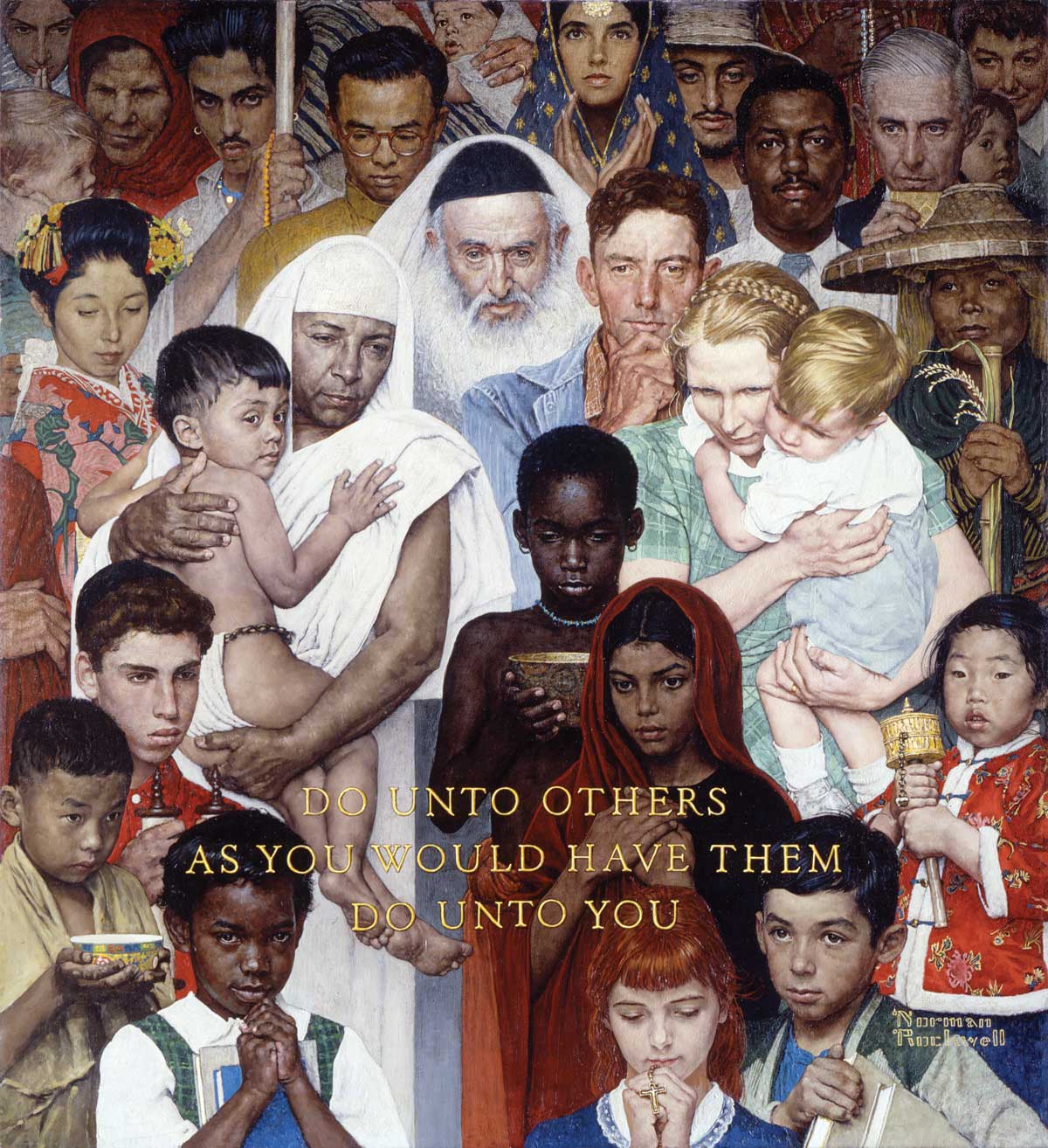

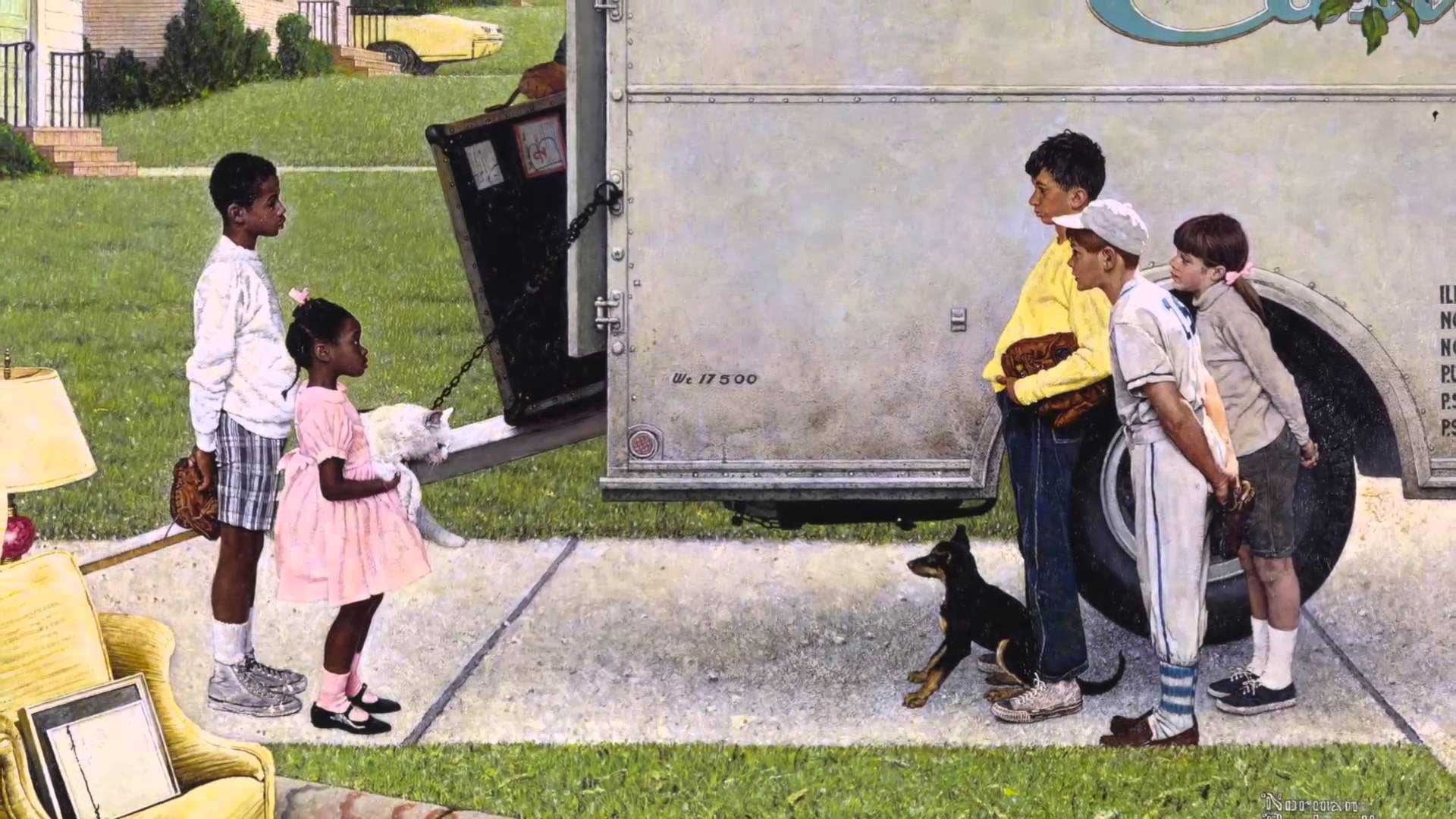

Mr. Rockwell did manage to illustrate a little African-American boy on a Post cover dated March 12, 1934. This was two years before the editor who limited those types of depictions retired from the Post. Yet, even on this cover Rockwell presented dignity although cloaked within those limitations placed upon him. The little boy showed respect in removing his hat before the white woman before him who, obviously, fell off of her horse. Although the little boy was dressed in what was socially constructed as acceptable he was standing before the lady who was sitting down before him. It is subtle but definite in how I perceive this to be almost indicating an equality between them. Fast-forward to the significant challenges of the 1960s which afforded Rockwell the opportunity to use his platform as America’s beloved artist to expand into what America really was on a broader scale. Besides, “The Problem We All Live With”, he was unleashed to reveal the complexity of the human condition for Black America through such paintings as “New Kids in The Neighborhood” and “Black Sheep in a Red Dress”. Norman Rockwell also went global with his tribute to all humanity with one of his defining classics, “The Golden Rule”.

I genuinely believe that if Norman Rockwell was with us today, he would have found a way to bring us an image of truth as well as hope in these outrageous times which the entire world is going through. Between the COVID-19 pandemic, and the ever-present pandemic of racism, I sincerely believe he could have, and would have, communicated to us. I believe he would be reminding us that although we are imperfect, and each one of us a “work-in-progress”, there is hope to lean on, believe in, to rise to the occasion. That is what he always did.

About the Blog Author

Please tell us what you thought of this article.