Before the rise of basic cable, Saturday mornings for many children in America were spent watching cartoons on one of three available television channels. From 1958 through the 1980s, a majority of those cartoons bore the Hanna-Barbera imprint. Creating scores of popular series such as The Flintstones, The Jetsons, Jonny Quest, Scooby-Doo, Super Friends, and The Smurfs, Hanna-Barbera was an animation powerhouse.

Hanna-Barbera: The Architects of Saturday Morning is the first museum exhibition on the world’s most successful animation partnership. The exhibit provides a glimpse of the extraordinary story of how two astute businessmen reacted to a dying film animation industry and revolutionized a new format for their product, while hiring the best talent in the business, and explores how their product transformed over the years and adapted through government restrictions, corporate changes, and changing viewing habits.

Hanna Barbera: The Architects of Saturday Morning was developed in partnership with Warner Bros. Consumer Products and has been sponsored, in part, by Keator Group, LLC, and the Max & Victoria Dreyfus Foundation.

ABOUT HANNA-BARBERA

1937-1957: THE RISE OF TOM AND JERRY AND THE DECLINE OF ANIMATED SHORTS

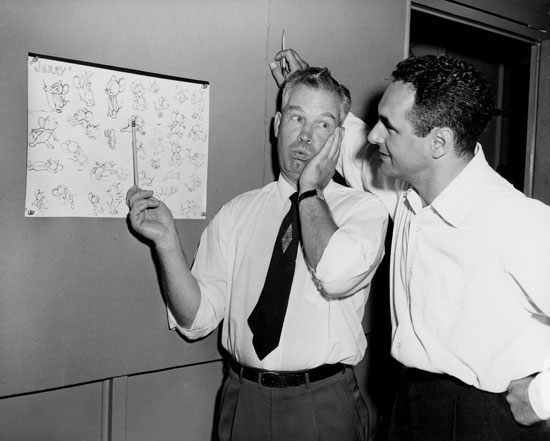

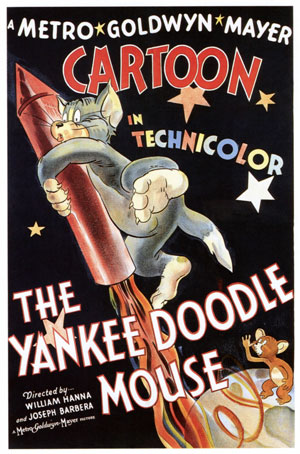

While working at MGM, Barbera asked Hanna “why don’t we do a cartoon of our own?” Barbera laid out a picture and Hanna timed it. It was a cat and mouse. Barbera recalled, “The minute you see a cat and mouse on the screen, you know it’s comedy.” While some of their colleagues enjoyed the cartoon, their producer Fred Quimby hated it, saying “Don’t make any more of them – you don’t want to put all your eggs in one basket.”

Tom and Jerry’s auspicious cinematic debut was in the animated short Puss Gets the Boot (1940). This cartoon provided Barbera a chance to work again with his old friend from New York, Harvey Eisenberg, who created the layouts. Though recognizable as Tom and Jerry, the characters were named Jasper and Jinx in this cartoon. It wasn’t until the second cartoon, The Midnight Snack (1941), that Tom and Jerry received their now-famous monikers.

PLANNED ANIMATION

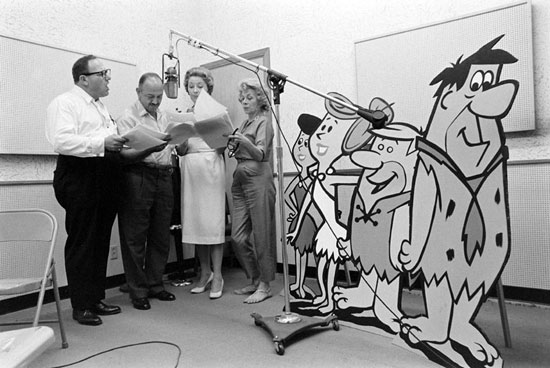

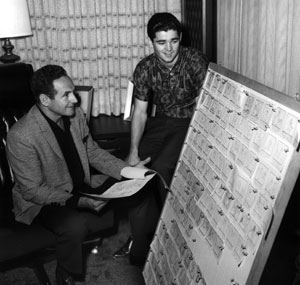

The closure of film animation units in the mid to late 1950s forced William Hanna and Joseph Barbera to reinvent the way animation was presented to the general public. Just as they were unsure about animating a cat and mouse duo in 1938, creating an animation studio devoted to television cartoon production would take talent, innovation, and hard work. In an 1987 interview, Barbera recalled, “Instead of $45,000 for five minutes like we had at MGM, we got $2,700. When we first sold Ruff and Reddy, Bill and I were taking in $40 a week for ourselves. I did the storyboards at home. My daughter Jayne colored in the drawings.”

1957-1960: HANNA-BARBERA’S EARLY YEARS

On the morning of Saturday, August 19, 1950, for the first time in history, children turned on their family television sets to find two shows that were meant just for them. Airing on ABC, Acrobat Ranch was hosted by Uncle Jim and featured circus acts performed by Tumbling Tim and Flying Flo, and Animal Clinic presented live animals with information that was aimed at a younger audience. TV was typically thought to be a family viewing device and it was unusual to see a show intended directly for young viewers. However, since it was determined that adults watched the least amount of television on Saturday mornings, it appeared to be an ideal time to air child-centered programming.

PRIME-TIME

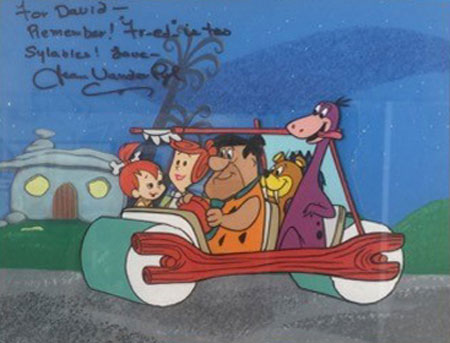

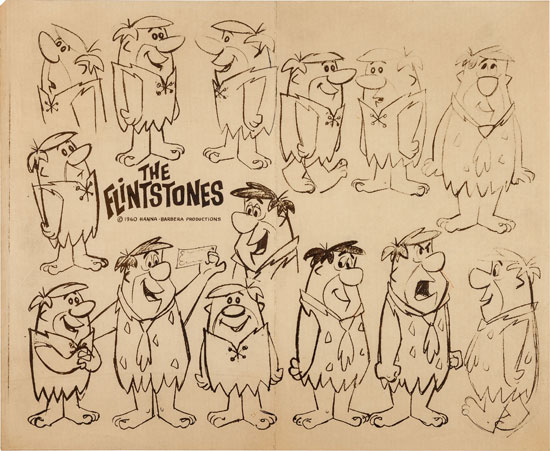

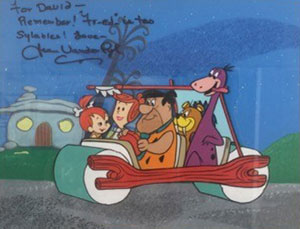

The debut of The Flintstones in prime-time in September 1960 was received horribly by TV critics. The New York Times referred to The Flintstones as “an inked disaster.” The Baltimore Sun called it “not a very good [comedy] inhabited by unpleasantly uncouth people.” TV critic Jay Fredericks claimed “I was solemnly assured by a local television official a couple of months ago that The Flintstones would be (a) hilarious and (b) THE show of the season. It is neither. The whole series is weak.” Thankfully, audiences disagreed and would follow the stone-age adventures of Fred Flintstone through 167 episodes over the next six years.

1960-1966: BUILDING ON SUCCESS

“The decade of the 1960s was, in essence, the salad years of Hanna-Barbera. Most of my old friends and veteran colleagues remember them as an incredibly fruitful period of television production.”

– William Hanna

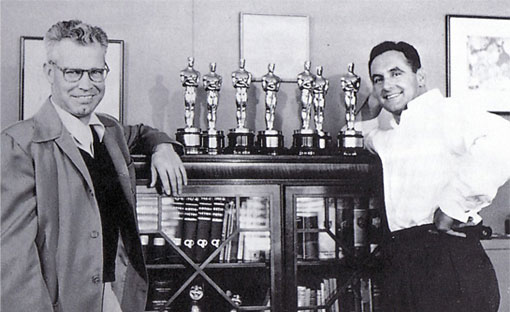

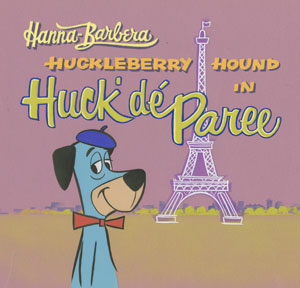

Fresh off the heels of successful series The Quick Draw McGraw Show and The Huckleberry Hound Show, which not only introduced Yogi Bear to the American public, but also awarded Hanna-Barbera the very first Emmy award for an animated series, Hanna-Barbera was unstoppable.

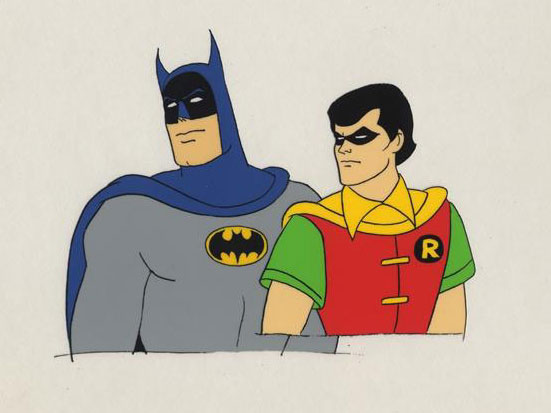

SPIES, SUPERHEROES AND ADVENTURERS

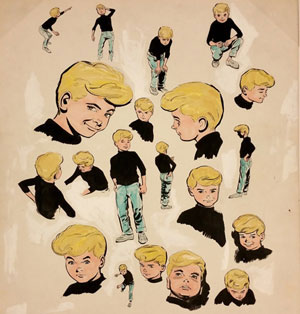

Always with an ear to the ground, William Hanna and Joseph Barbera were cognizant of trends in popular culture. As their audience aged, Hanna and Barbera became aware that many cartoon viewers were becoming interested in the escapades of James Bond on the big screen and the adventures had by Spider-Man, The Fantastic Four, and the Justice League in the pages of comic books. They made a decision to begin transforming much of their Saturday morning fare into the action/adventure genre. William Hanna noted, “…Jonny Quest became one of our most popular shows, and it eventually launched a whole platoon of other Hanna-Barbera cartoon series in the action-adventure genre, including among others The Fantastic Four, Space Ghost, The Herculoids, and The Galaxy Trio.” The first season of Jonny Quest proved to be very popular. Airing in prime-time, the series’ unique style, superb musical composition by Hanna-Barbera veteran Hoyt Curtin, and inclusion of futuristic technological innovations enamored viewers young and old.

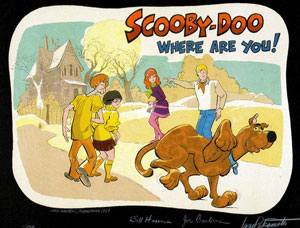

THOSE MEDDLING KIDS…

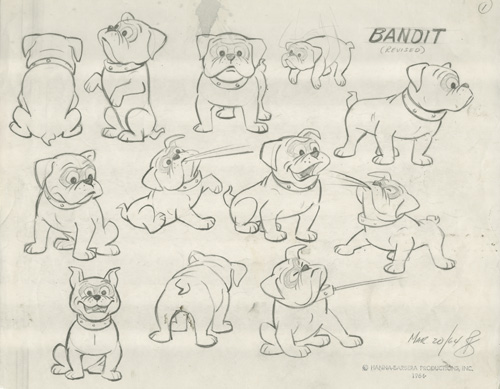

In 1968, CBS executive Fred Silverman, a fan of animation, worked closely with Hanna and Barbera to develop an idea of an animated team of mystery solvers. The characters who would become Fred and Shaggy were influenced by Dwayne Hickman’s Dobie Gillis and Bob Denver’s Maynard G. Krebs, characters from the early 1960s CBS series The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis. The recent ABC series, The Mod Squad, which featured a multi-cultural group of hip young detectives, informed the cartoon’s overall look and design. Geoff Jones, Mike Andrews, Kelly Summers, Linda Blake, W.W., and their dog, Too Much, formed the group in Mystery’s Five.

1966-1987: HANNA-BARBERA CONQUERS SATURDAY MORNINGS

Due to pressure from the group Action for Children’s Television in the late 1960s, Hanna-Barbera was forced to address complaints of violence in its cartoons. One successful example of fluffier fare included Hanna-Barbera’s first series to feature live-action segments with cartoons. In a throwback to TV cartoon presentations from the 1950s, Hanna-Barbera began developing a program of animated shorts introduced by hosts, in this case humans in animal suits that were designed by pre-fame producers Sid and Marty Krofft. Before the team of Fleegle, Drooper, Bingo, and Snorky were named The Banana Splits, they had gone through several name changes, including Kellogg’s Korny Kritters, Kellogg’s Presents the Hanna-Barbera Happy Hour Starring the What Furr’s, and The Banana Bunch.

1987-2001: THE LATER YEARS

A major turning point in the history of Hanna-Barbera is marked by the sale of long-time owner Taft Broadcasting to Great American Broadcasting in 1987. According to Iwao Takamoto, once Taft was acquired by Great American Broadcasting, they planned an eventual sell-off of Hanna-Barbera. They wanted to sell as many shows as possible and get them on the air in order to make an eventual sale of Hanna-Barbera more attractive to buyers. This resulted in a sudden increase in output where quantity was preferred over quality.

October 4, 2014: A Little Magic Has Been Lost

With the CW network’s decision to begin airing live-action educational programming during the Saturday morning block, October 4, 2014 marked the first moment in over fifty years without Saturday morning cartoons on broadcast television. Some of the factors involved in the demise of Saturday morning cartoons include political pressure groups like Action for Children’s Television which first dumbed down cartoons in the late 1960s then hastened the move of animation from broadcast TV to cable where programs did not have the same restrictions, the rise of basic cable that began in the late 1970s, the introduction of infomercials and college football which provided cheap programming, and, finally, streaming video.

A TRIBUTE TO THE ARTISTS AND WRITERS OF HANNA-BARBERA

With the decline of animated film production in the mid-1950s, upon forming Hanna Barbera Enterprises in 1957 Hanna and Barbera began recruiting the best writers and artists in the business. Because of mass layoffs in the industry, they were able to hire seasoned veterans like Michael Maltese, Warren Foster, Dan Gordon, Tony Benedict, Art Scott, Willie Ito, Kenneth Muse, Alex Lovy, and Carlo Vinci. Additionally, many Disney employees were laid off after Sleeping Beauty ended production and were now available for work at Hanna-Barbera. Many of these men are responsible for Hanna-Barbera’s most memorable cartoons, including The Huckleberry Hound Show, The Yogi Bear Show, The Flintstones, The Jetsons, and Quick Draw McGraw.

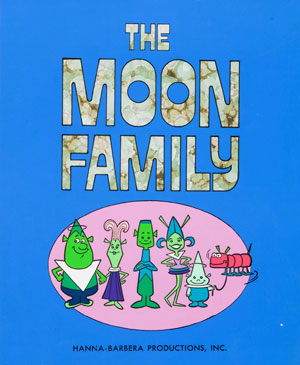

UNPRODUCED PROJECTS

Within the exhibition catalogue will be images of dozens of presentation boards for unproduced series. They are just a small sample from more than 300 unrealized projects conceived by Hanna-Barbera from the 1960s through the 1980s that exist in the Hanna-Barbera archives.

IMAGES

RELATED EVENTS

MEDIA

VENUE(S)

Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, MA November 12, 2016 through May 29, 2017

DIRECTIONS

Norman Rockwell Museum

9 Route 183

Stockbridge, MA 01262

413-298-4100 x 221

Download a Printable version of Driving Directions (acrobat PDF).

Important note: Many GPS and online maps do not accurately place Norman Rockwell Museum*. Please use the directions provided here and this map image for reference. Google Maps & Directions are correct! http://maps.google.com/

* Please help us inform the mapping service companies that incorrectly locate the Museum; let your GPS or online provider know and/or advise our Visitor Services office which source provided faulty directions.