| New Perspectives on Illustration is an engaging weekly series of essays by graduate illustration students at MICA, the Maryland Institute College of Art. Curators Stephanie Plunkett and Joyce K. Schiller have the pleasure of teaching a MICA course exploring the artistic and cultural underpinnings of published imagery through history, and we are pleased to present the findings of our talented students in this weekly blog.

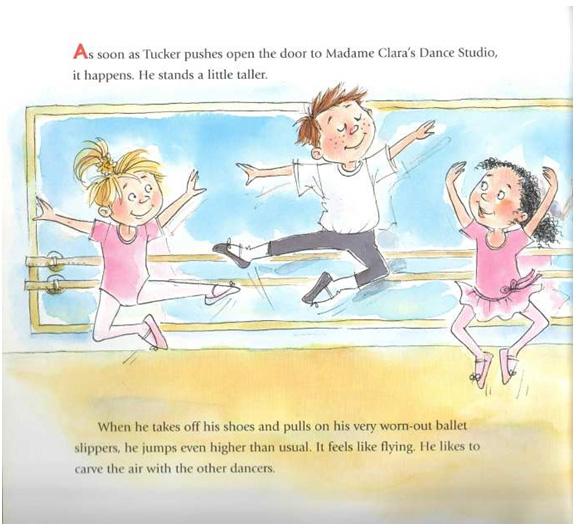

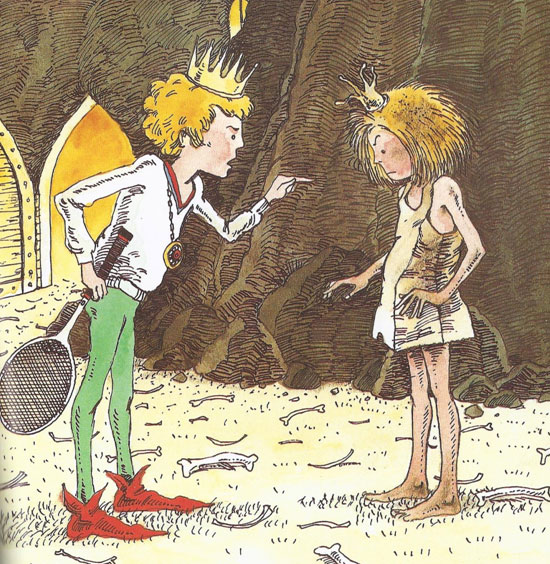

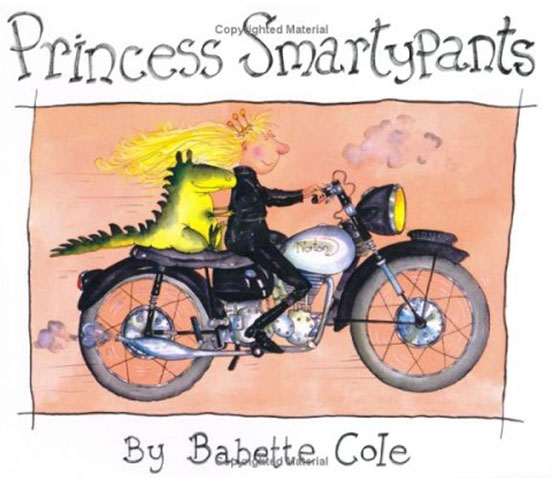

Contemporary Gender Roles in Children’s Literature by Joshua Heinsz examines the influence of illustrated children’s books on how gender roles are assigned and understood in contemporary society. Contemporary Gender Roles in Children’s Literature An Essay by Joshua Heinsz Gender roles are established very early in a child’s life. In fact, it has been determined that most children are able to identify themselves as either a boy or a girl by the age of three. While there is no definitive evidence that children’s literature is a major factor in how gender role’s are assigned and stereotyped, the importance of the messages in said works cannot be denied. By engaging in these fictional worlds, consciously or not, children will project themselves as the characters in their beloved stories and the roles that they play can become integral to the child’s personality development. More often than not, male characters are assigned to more dominant roles, exerting strong leadership abilities and displaying the need for toughness and a necessity to suppress emotion. This stems from the stereotype that men must be strong, and parents enforce this idea to prevent their boy from being raised as a “sissy”. Which to use the word “sissy” as a negative connotation is a problem in and of itself as it is associated with the feminine and suggests that both feminine and negative are synonymous to young boys. In contrast to the male characters, leading ladies have tendencies to be mild mannered, submissive and worst of all: damsels in distress. They are often involved in both tales and decorum of frivolity and lack the substance of character that is to be instilled in young men. Aside from literature with female leads, it is even more problematic in works targeted to a male audience. In said stories, the cast of girl characters is often minimal, lacking dimension and suppressed under the roles of the boys. This therefore subconsciously teaches young boys that they indeed are the more important roles in society. When it comes to children’s literature, these stereotypical gender roles are just beginning to come under fire. While the issue of race diversity within the genre has been explored and evolved over the past several decades, we still have a long way to go when it comes to teaching individuality in children and the disregarding of stereotypes. One of the more notable children’s books of late to address this issue and breaking some of the barriers of gender roles is Pinkalicious. The story is co-written by Elizabeth and Victoria Kann, with illustrations by the latter. While the illustrations are bright and pink and our heroine very much representative of society’s current ideas of what girls should enjoy, the forward thinking comes from the father and the brother figures in the story. While both snub the excess of the color pink, her brother Peter in the end embraces his love of the color as well. While this is a franchise very much directed at young girls, it does at least convey the message to them that it is quite alright for boys to love what is primarily considered a “girl color” as well. Rewinding a bit to the year of Nineteen Eighty, we have a much more forward thinking plot with Robert Munsch’s Paper Bag Princess with illustrations by Michael Martchenko. For those unfamiliar with the tale, we are presented with our lovely ingénue, Princess Elizabeth who is to be wed to the handsome and dapper Prince Ronald. In a what happens to be not-so-unfortunate turn of events a dragon interrupts the preparations and not only burns down Elizabeth’s castle and belongings, but kidnaps her prince as well. After finding nothing more than a paper bag to adorn her body with, Elizabeth treks all the way to the dragons cave and uses cleverness and wit to trick the dragon and rescue the prince. After risking her own neck, the spoiled prince is so ungrateful for her deeds all because she looks unrefined in her paper bag garb. Being the excellent role model she is, Elizabeth doesn’t think twice before calling Prince Ronald a “bum” and hightailing it to her own happily ever after without him. A little closer to the present, we were given a similarly strong princess role model in the form of Princess Smartypants, written and illustrated by Babette Cole. In this tale, our heroine is perfectly content with her life the way it is and the company of monster friends that she keeps. Despite her mother’s wishes, Smartypants is perfectly happy to remain a “Ms.” With a number of suitors calling for her, Smartypants foils nearly every one of them with the help of her creature friends. When at last she is nearly outdone by a prince, she simply turns him into a frog, therefore scaring away all past, present and future suitors so that she may live her days in harmony with her friends in the way she so chooses. Both above princess tales are excellent examples of the direction more contemporary children’s book writers and illustrators should consider when storytelling for young audiences. I would say this is especially so with the Paper Bag Princess. Princess Elizabeth is strong and independent, while still virtuous and true. It is important that poise and good manners are not shunted aside in these tales as well. Characters can still be well rounded and modern without losing morals that are traditionally positive for both genders. Though we can indeed say there is a notable increase in these strong leading ladies to set more positive examples of femininity, there is still a distinct lack of advancement when it comes to children’s books for young men. On the whole, literature for young boys still very much preaches the importance of what are in truth unhealthy notions: a lack of full emotional range, conformity and undermining what is often misconstrued as weakness. These supposed weaknesses also tend to be associated with the feminine and further perpetuate gender-skewing stereotypes. With such a hole left in the market for books moving beyond the traditionally considered traits of masculinity, The Only Boy in Ballet Class, written by Denise Gruska and Illustrated by Amy Wummer, is truly a breath of fresh air. Here we meet Tucker who doesn’t want to play football like the other boys; he instead has a passion for dance. His peers give him much grief, but despite being considered strange, Tucker still has the courage to pursue his passion. Then when he is suddenly needed to help the football players, it is his dance skills that lead the team to victory. While it would perhaps be nice if the message did not have to be conveyed through such a stereotypical sport, it is still appreciated all the same. In the end, Tucker and his love of dance are embraced and his uniqueness is glorified. The virtues behind The Only Boy in Ballet Class need to be more widespread in the culture we create for young boys. Not every young man is destined to be a star athlete, and certainly none should be taught that suppressing their emotions is a sign of strength. Being called a “sissy” or a girl should not be given a negative connotation and having an appreciation of or desire to engage in what are considered girlish activities should be embraced and not frowned upon. Times have changed and so have modern gender roles. Women are easily capable of becoming mechanics, CEOs and racecar drives. Men are equally as capable of being chefs, nurses and stay-at-home dads. None of the above demoralizes one’s femininity or masculinity, and society is increasingly pushing forward to embrace a broader definition of gender. So if we as adults are breaking tradition, is it not our responsibility to ensure these new inclusive ways of identifying ourselves should not be more readily taught to children in one of their most vital methods of learning? Society is evolving, and it is time picture books did the same.

Cole, Babette. Princess SmartyPants. New York: G.P. Putnam and Sons, 1986. Flood, Allison. “Study finds huge gender imbalance in children’s literature.” The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2011/may/06/gender-imbalance-children-s-literature. Glenn, Whitney. “Helping Children Understand Gender Roles and Avoid Gender Bias.” http://voices.yahoo.com/helping-children-understand-gender-roles-avoid-316207.html?cat=7. Gruska, Denise. The Only Boy in Ballet Class. Layton, UT: Gibbs Smith, Publisher, 2007. Institute for Humane Education. “12 Picture Books that Challenge Traditional Gender Roles.” Humane Connection. http://humaneconnectionblog.blogspot.com/2012/06/12-childrens-picture-books-that.html. Kann, Elizabeth and Victoria. Pinkalicious. New York: Harper Collins. 2006. Kid Source Online. “Gender Issues in Children’s Literature.” http://www.kidsource.com/education/gender.issues.l.a.html. Munsch, Robert. The Paper Bag Princess. Willowdale, ON: Firefly Books, LTD. 1980.

|