New Perspectives on Illustration is an engaging weekly series of essays by graduate illustration students at MICA, the Maryland Institute College of Art. Curators Stephanie Plunkett and Joyce K. Schiller have the pleasure of teaching a MICA course exploring the artistic and cultural underpinnings of published imagery through history, and we are pleased to present the findings of our talented students in this weekly blog.

Mafalda and Peanuts by Valeria Molinari explores the significance and art of noted Latin American cartoonist Salvador Lavado, known as Quino, and the relationship between a loudmouthed, opinionated six year old and Charles Schulz’s quiet, lovable Charlie Brown.

By Valeria Molinari

Comics come in all shapes and sizes, and the ones we grow up will stay with us forever, but somehow the answers are different depending on the country or continent. When you ask most American’s what comic strips they grew up reading, the answer somehow always comes back “Peanuts”, by Charles Schulz. That answer might even be true in some parts Latin America, but that is not always the case. There is a more influential comic, and the majority of people in the southern part of the continent grew up reading Mafalda, by Joaquín Salvador Lavado, better known as Quino. Even though they did not debut at the same time, they were printed simultaneously for two decades between the 1960’s and 1970’s. The common thread between them is not only the palpable existentialist questions that the characters seem to ask each other, but the fact that both cartoonists used children around the same age (six to eight), which probably made them get away with saying pretty much anything. The use of children is probably because it is less threatening to have a child address a very important or socially heated topic, than to have a serious adult talking about it.

Schulz debuted Peanuts in October of 1950 in the United States, with the main character of Charlie Brown, a lovable, insecure, sport-loving, existentialist boy with terrible luck. 14 years later Quino introduced Mafalda in September of 1964 in Argentina, she was a rebel non-conformist six year old who along with her friends is trying to figure out politics, life, and the world. These strips ran concurrently through “The Sixties” and “The Seventies” (the decade1963-1974).

Those were times of worldwide change; human, gender, and race rights were being fought, political problems were escalating in places like communist Russia, Germany, Cuba, and China. Both authors’ addressed social issues, but in very different ways; Schulz’s was more implicit, whereas Quino’s way was much more blunt.

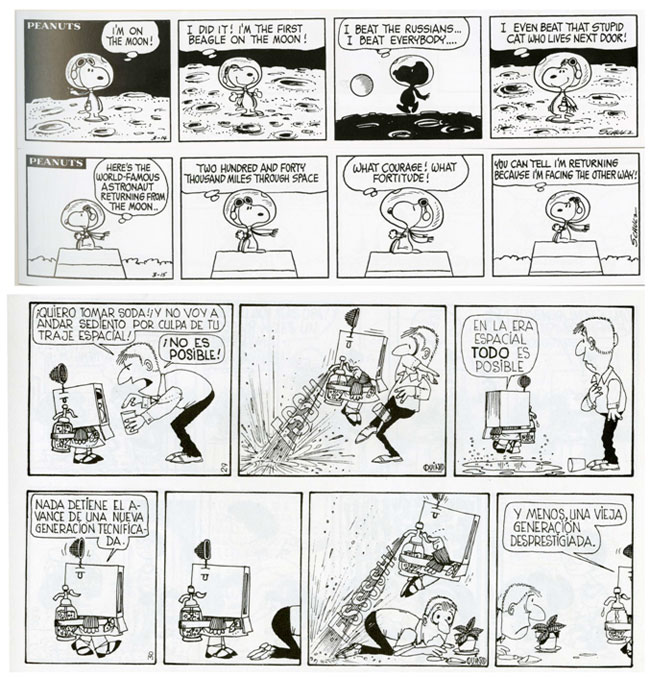

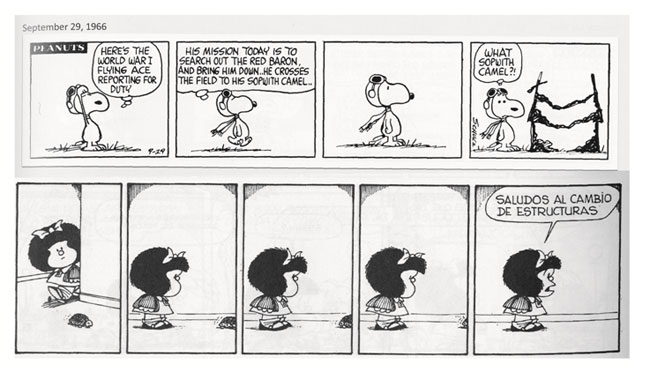

The culture of the times was probably what influenced the way both cartoonists approached their writing. Schulz began Peanuts in the Fifties, in a much more conservative society, where most women were homemakers, and the dads were the bread-earners, and social issues were not necessarily dinner conversation; while Quino started Mafalda in the Sixties amidst of a social revolution, and the bluntness that enveloped almost every one Mafalda’s strips with political or social content was what made it so fresh. While Peanuts also had satirical social commentaries of the “real world”, these comments were more refined, and less blunt than Mafalda’s rants, such as, addressing the “Space Race” (See Fig. 1), the Vietnam War, Religion, and existentialism in general.

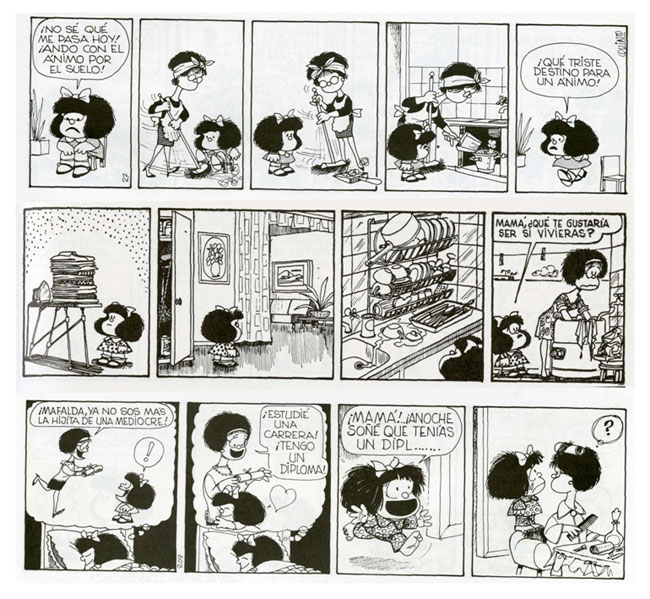

Schultz also addressed feminism in a more delicate way with the character of Peppermint Patty a tomboy, football-loving girl with freckles. On the other hand Quino writes about

Feminism in a much open way, especially in some strips when Mafalda interacts with her mom (Raquel) trying to relate here “crummy” life as “just a housewife” to that of an intellectual, and “accomplished” woman. (See Fig. 2)

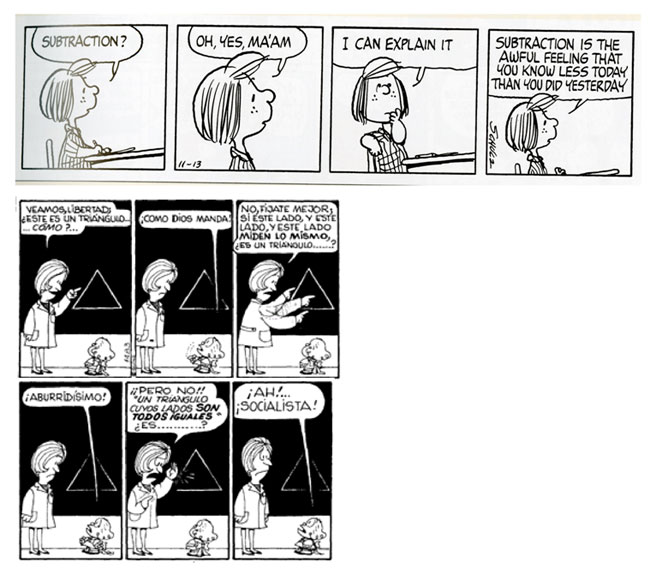

Another distinct differences between Schulz and Quino is the way they decided to portray adults. In Peanuts the adult’s (teachers, parents, etc.) voices always appear as this unique gibberish sound “mwa mwa mwa mwa” as if to purposefully devalue the meaning of their words, and therefore accentuate the meaning of the child’s opinion. Contrary to Schultz, it was important for Quino to show the parents and other adults, because he felt the strip would have deeper roots, and it was important for him to show strong family values. (See Fig. 3)

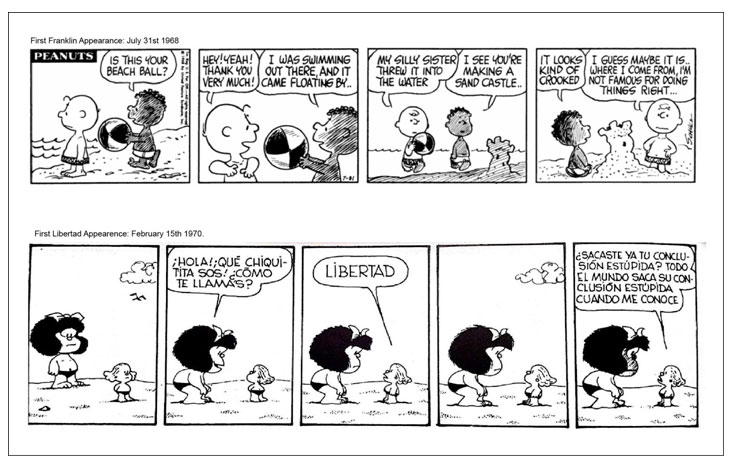

An interesting similarity between both artists was the way they introduced new characters that became transcendental to the story. For instance, in 1968 Charlie Brown meets his later-to-become-classmate Franklin; and the fact that he was African-American in a racially integrated school, and neighborhood was a not even a question, it was just part of the strip. When asked about it Schultz said “I had always thought that black people might feel I was doing it in a patronizing or condescending manner. Then I received two letters from back fathers asking that Peanuts be integrated. That was the turning point”. One of the most notorious characters in the Mafalda universe is named Libertad (Freedom), she is highly outspoken, and a yeller, which is contrasting with her height; she is the smallest of all the children in the strip, even smaller than Mafalda’s little brother who is 6 years younger than her. Both Franklin and Libertad met the main characters of their individual stories at the beach, but two years apart; while Franklin first appearance ran in 1968, Libertad’s was in 1970. (See Fig.4)

There are also very similar characters in the world of Charlie Brown, and Mafalda; for example crabby-bossy-opinionated Lucy, and her counterpart Susanita (Little Susan). Both characters are alike, and although they live at the opposite ends of the same continent they share some of the same goals. They are both in love with another main character in the strip, and are very selfish in their daily lives.

Even if we can find various similarities between some characters one thing is very difference, their pets: Burocracia (Bureaucracy) and Snoopy (See Fig.5).

Mafalda’s owns a tiny turtle that is barely a part of the strip, contrary to that we have Charlie’s beagle, which became a beloved and transcendental character in the strip. Schultz gave Snoopy more than one hundred alter egos (The WWI Flying Ace, Joe Cool, a helicopter, World Famous Surgeon, among others). This character evolved enough to think, write books, he even plays and interacts with other characters, and has entire strips dedicated to his antics, and his sidekick Woodstock. Sometimes it seems it feel as though Snoopy’s is the only adult or mature voice in the comic.

Despite them having different styles and contrasting approaches to the same subjects, both comics were so popular that they were translated to different mediums, one of them being animation; and while Peanuts started as a black and white strip in the Fifties, it was later translated to color, as did its animation. On the other hand Quino started Mafalda in black and white as well, but there was never any color on her until her animation in 1979. Various social and human rights activists also approached Quino in order to use Mafalda as the voice of their campaign, such as United Nations, UNICEF, and Human Rights Association, and ever since then she has been known as the voice of such issues.

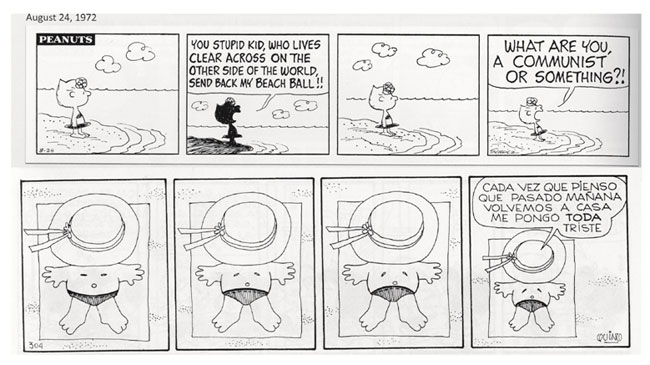

Both Mafalda, and Charlie Brown are worldwide famous, but for some reason Mafalda never made it across the US border. In an interview for Costa Rica’s newspaper “La Nación” Quino said, “The North Americans have so many talented cartoonist. Why would they publish us?” and while that might have been one of the reasons, probably the bluntness of the cartoon was also one of them. In some of the strips the adults as well as the children use the word “damn”, and even if that is not necessarily a curse-word, it was definitely frowned upon in the US especially in the sixties. The use of nudity might have also been a pivoting point (See Fig), while it is normal for a child in South America and Europe to not wear a top while wearing a bathing suit; Schulz draws Sally (Charlie’s sister) wearing a two-piece suit while at the beach. (See Fig. 6)

Famous Italian writer Umberto Eco wrote the introduction of the first Mafalda book to ever be published in Italy, and in it he compared her to Peanuts. Quino was not necessarily happy with the idea of his strip being linked to Schulz’s. Saying that even if he studied Schulz’s books before creating the advertising campaign that will later inspire Mafalda; the cartoons were completely different; saying Mafalda had much more political and social content, and had very strong family content whereas in Peanuts was more mild, and playful.

However Peanuts ran for 27 years after Mafalda’s last strip in 1973, they are both beloved internationally, and while there is no record of Quino ever meeting Schultz, they probably would have had a very interesting conversation about their distinct approaches to the subject of cartooning, and their very different characters. We could probably pin point every single detail in which they both coincide and contrast, but the important thing behind these two comics is the legacy behind it. The impression they made the first time we read them, and how they shaped us and made us more aware of our surrounding, ourselves and the echo that still resounds in our society as we introduce them to a new generation.

Bibliography

“Entrevista con Quino.” La Nacion

Inge, Thomas. Charles M. Schulz: Conversations. University P of Mississippi.

Michaelis, David. Schultz and Peanuts. New York: Harper Perennial, 2008.

Quino. “Quino. Sitio oficial de Quino.” Quino. Sitio oficial de Quino. 09 Dec. 2012<http://www.quino.com.ar/>.

Quino. Toda Mafalda. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Ediciones de la Flor, 2001.

Quino. “World of Quino [Paperback].” Holt Paperbacks. 09 Dec. 2012.

Schulz, Charles. Celebrating Peanuts: 60 Years. Andrews McMeel.