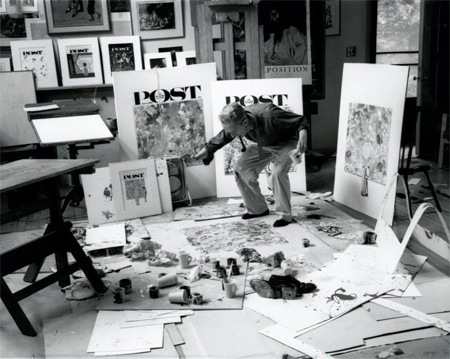

Norman Rockwell, The Connoisseur, 1961. Cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, January 13, 1962. Image © SEPS, Indianapolis, Indiana. All rights reserved.

June 17 through October 29, 2016

This exhibition is sponsored by

The essence of tradition is to invite the challenge that redefines it, and after fifty years on the periphery, realism is being reinvigorated by contemporary artists who see it as a way to address the experiences of living in our complex world. In post-World War II America, the primacy of abstract art was clearly acknowledged, and by 1961, when Norman Rockwell painted The Connoisseur―his visual treatise on the subject juxtaposing Jackson Pollock’s nonrepresentational art with his own illusionistic imagery―Abstract Expressionism had been covered in the popular press for nearly fifteen years. By the mid-1950s, abstraction had successfully attracted collectors and critics whose passion for these visceral, less readable artworks was in itself noteworthy.

Rockwell was working at a time when he and other figurative painters like Andrew Wyeth were criticized for their predilection for visual storytelling. In The Connoisseur, Rockwell had cause to defend himself against his detractors and take a good-humored poke at the pieties surrounding abstract painting. In the 1950s, there was heated debate about the relative merits of abstract art, realist art, and illustration art, and Rockwell was frequently caught in the crossfire. Clement Greenberg, one of the most vocal critics of the period and a champion of Pollock and other New York School artists, set the conversation’s terms. He argued for aesthetic complexities and challenges of abstract art while protesting the cheapened kitsch culture that he felt dominated America. In Greenberg’s lexicon, Rockwell’s illustrations were kitsch, popular accessible artworks that appealed to the masses. When such popular forms become the dominant taste, Greenberg argued, the high arts are challenged to flourish and survive―a danger in a society as populist and commercial as the United States.

Reference photo by Louie Lamone. Norman Rockwell Museum Collections. ©Norman Rockwell Family Agency. All rights reserved.

Even in the world of illustration, Rockwell represented the tried and true representational approach to picturemaking that dominated most American commercial art from the mid-1930s until the mid-1950s. His influence on the genre was widespread, and those who slavishly followed his surface style were widely published. Hence Rockwell drew respectful fire from young rebels, but his many imitators earned their contempt.

Such arguments set the parameters by which Rockwell and other realists were judged by modernist art critics at the time, and by some art commentators today. The Challenge of Realism will examine the forces that have inspired the resurgence of realist painting in recent years, and the ways in which our contemporary viewpoints have been shaped by post World War II constructs. Is it possible in this age of instant imaging that we remain challenged to view realist painting as serious, meaningful work, or have former lines of distinction been blurred in the face of ever-increasing visual access? In what ways has contemporary realism come of age as a reflection of its time? What is the relationship of contemporary realism to the published art of the mid-twentieth century, and to artistic movements of the past? How are the extremes of technical absorption and narrative context balanced in the creation of resonant realist images today? In the end, it is the voice and vision of the artist, and not the creator’s technical and narrative ability alone, that makes a work of art.

The Challenge of Realism will explore these significant questions through the juxtaposition of contemporary realist painting and the popular imagery of the mid twentieth century. Original artworks and commentary by Mark Tansey (b. 1949), whose large scale monochromatic allegories reference the art of photography, a pivotal technology in the reproduction and dissemination of popular images; John Currin (b. 1962), who has referenced the art of Norman Rockwell, and whose provocative figural paintings reflect upon domestic and social themes that were prevalent, though differently portrayed, in the mid-twentieth century; Vincent Desiderio (b. 1955), whose dark intellectual melodramas re-imagine scenes of crime and adventure from pulp fiction; Lucien Freud (1922-2011), the painter of deeply psychological works that examine the relationship of artist and model; and Jamie Wyeth (b. 1946), son of noted painter Andrew Wyeth and grandson of illustrator N.C. Wyeth, whose images convey stories real and imagined, among other artists, will be featured in the exhibition and its accompanying catalogue.