Museum intern Devan Casey uses original letters from the Museum’s Archives to learn more about audience response to The Problem We All Live With in 1964.

A New View of Norman Rockwell’s

By Devan Casey, Norman Rockwell Museum Intern

The Norman Rockwell Museum is very unique. It attracts people of all ages from all around the world to visit. I’ve heard adults saying “I remember selling that copy of The Post door to door!” or seen children’s excited faces when they find something on the scavenger hunt list. The Rockwell Museum has something for everyone, and this summer I was lucky enough to receive an internship there.

When you walk into the main gallery at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts you see a collection of Rockwell’s world famous and carefree illustrations depicting small town America. For me one wall in this gallery does not seem to fit in with the light hearted theme. The two paintings have a serious tone case upon them−not Mr. Rockwell’s usual style. I found myself face to face with murder, hate, and Norman Rockwell’s more controversial paintings. These two images are Murder in Mississippi (1965) and The Problem We All Live With (1964).

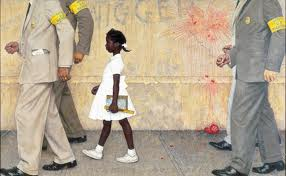

After working with the Saturday Evening Post for over forty years Rockwell cut ties and began painting for LOOK Magazine in 1963, debuting his LOOK career with The Problem We All Live With. This painting is Rockwell’s take on Ruby Bridges’ first day at an integrated school in New Orleans, Louisiana. The painting depicts a young African American child on her way to school, flanked by four U.S. Marshalls. Above her racial slurs and the ominous acronym “KKK”. You notice a red splatter on the wall and then on the sidewalk, the red mess of a recently thrown tomato. Not only are you looking at a strong, determined little girl, but Rockwell has chosen to put us (the viewers) in the place of the angry mob.

As if this painting wasn’t powerful enough standing alone, there is a letter on display that hit me just as hard as the painting. A Tennessee man named Chester Martin wrote to Rockwell and said, “I have never been so deeply moved by a picture…Thank you for showing this white Southerner how ridiculous he looks.” This letter astounded me because thanks to Norman Rockwell this man had such a powerful and transforming experience from a painting. This showed me the transforming power of art. However, not all of the reactions were positive ones. After expressing my interest in this piece to the Chief Curator and Deputy Director Stephanie Plunkett, she showed me into the archives where I spent about an hour thumbing through letters written after the piece was published to and from Norman Rockwell and a variety of different people about the piece, and sad to say not every letter was positive.

One New Orleans man, G.L. LeBon, sent one of the most hate filled letter’s I’ve ever read. I even had to stop and reread parts of the letter to make sure I wasn’t imaging the words on the paper. Here are a few lines from his letter just to illustrate how enraged LeBon was.

“Anybody who advocates, aids or abets the vicious crime of racial integration is nothing short of a traitor to the white race.”

“It is nothing short of a heinous crime to mix little white and black children and brainwash them with the infamous lie that the only difference between the white and black races, is the color of skin.”

“THERE CAN BE, AND THERE WILL BE, NO COMPROMISE WITH THE VICIOUS CRIME OF RACE MIXING AND INTERGRATION. THE WAR HAS JUST BEGUN!”

This man also stated that he was willing to put five thousand dollars (today’s equivalent of thirty seven thousand dollars) on the line to prove his point.

While there was not one positive line in this letter it did bring one note of joy to me. The reaction. Even though this letter was one of the most ignorant things I’ve read it excited me on the vast reaction it got. It meant that people were paying attention. The fact that this painting got so much attention and caused so much controversy amazes me.

Now I’ve always been fascinated in people’s reactions to artwork, and reading this letter just revamped that fascination. So I decided to spend about an hour and a half up in the gallery watching people react to this painting. I noticed that people lingered at this painting. A somber look spread across their face, their eyebrows furrowed together as they studied the painting, absorbing every detail Rockwell painted fifty years ago. I overheard a woman saying to her husband, “I remember that, and I remember when this was in LOOK. Incredible.” I asked her what her reaction to the painting was. She looked at me and said one word, “sad.” She went on further, “ Every time I look at this painting I feel so sad for that little girl. She was so innocent and was thrust into the news. Rockwell could force great emotions

Her reaction wasn’t the only one that stuck with me.

I saw a mother and her two sons looking at the painting. The two boys were admiring the painting when I went over to speak with them. I asked them if they knew what was going on in the painting. They didn’t. I briefly told them about Ruby Bridges and what the painting was showing and their jaws dropped in disbelief that something that awful could happen to anyone. I asked them how it would feel if they were in her shoes. “That’s scary. But those men were good ‘cause they were walking with her, right?” I thought it was incredible that even a five year old could quickly grasp the story Mr. Rockwell was trying to tell.

Fifty years later this painting is still leaves its mark on the world. The simple, yet deeply complex painting, still attracts crowds and can evoke a wide range of emotions in those who come in contact with it. The Problem We All Live With is just another example of how artwork can spark controversy, induce great emotions in people and have an impact on our entire country, even decades after it was painted. Art is truly timeless.