Masters of the Golden Age: Harvey Dunn and His Students

June 24, 2016 through September 25, 2016

Hunter Museum of American Art, Chattanooga, TN

November 7, 2015 through March 6, 2016

Norman Rockwell Museum

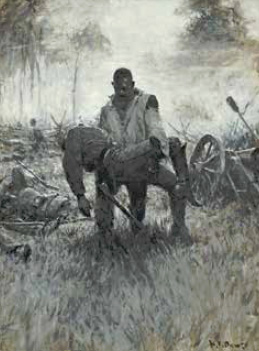

Norman Rockwell Museum and South Dakota Art Museum are honored to present the first major exhibition celebrating the art and legacy of American illustration master, Harvey Dunn. A brilliant and prolific illustrator of America’s Golden Age, Dunn was a prodigy of legendary artist Howard Pyle, and an admired teacher in his own right. Born on a homestead near Manchester, South Dakota, he left the farm to study at the South Dakota Agricultural College and the Art Institute of Chicago before becoming one of Pyle’s most accomplished students—along with N.C. Wyeth and Frank E. Schoonover—and eventually opened his own studios in Wilmington, Delaware, and in Leonia and Tenafly, New Jersey. Of his mentor, Dunn said, “Pyle’s main purpose was to quicken our souls so that we might render service to the majesty of simple things.”

In 1906, Dunn obtained his first advertising commission from the Keuffel and Esser Company of New York, and throughout his prodigious career, he created painterly illustrations for the most prominent periodicals of his day, including Scribner’s, Harper’s, Collier’s Weekly, Century, Outing, and The Saturday Evening Post. Exceptional examples of Dunn’s art for publication are featured in this exhibition, which also highlights the artist’s powerful work for the American Expeditionary Forces, recording the unforgettable realities of combat. During World War I, Dunn was one of eight war artists assigned to the American Expeditionary Forces in France. He struggled emotionally as a result of his wartime experiences, but found solace in painting visions of the prairie, inspired by his boyhood memories and his love of South Dakota’s landscape and history.

This exhibition is a collaboration of Norman Rockwell Museum and South Dakota Art Museum, Generous support has been provided by First Bank & Trust and The Max & Victoria Dreyfus Foundation

Stephanie Haboush Plunkett

Deputy Director/Chief Curator

Norman Rockwell Museum

Harvey Dunn has been gone for over sixty years and renewed interest in his work is long overdue. Why? Because we need him again. Look around. Is there any artwork today that approaches the level of Harvey Dunn, his mentor Howard Pyle, or contemporaries that shared in Pyle’s teachings? Even in Dunn’s time, his unique philosophy was not for every student because it was simply too demanding, yet his thoughts on the process of making pictures drill down to each of us at such an individual level that the message is easy to miss.

To the Pyle faithful, the nature of what constitutes a picture—the very word itself—needs clarification. A picture is more than a drawing or painting in a frame, more than a couple of juxtaposed images in an interesting arrangement. In fact, it is more than the sum of all its compositional elements. To these painter-illustrators, an artist “composed” a picture in the same way movements of a symphony are arranged, creating sounds that reach deep into the emotions. Similar to classical music or great literature, a picture—an illustration—could rise above its subject matter and impart a greater truth. After all, did Melville set out to write Moby Dick because he wanted to tell us about a whale? What did Copland tell us about an Appalachian Spring?

Dunn’s South Dakota prairie background, combined with his legendary work ethic, was the stuff of American folklore. He quickly grasped Pyle’s philosophy and added a sodbuster’s grit. He was the size of a linebacker and spoke of art like Vince Lombardi—and he had a lot to say. You can find your own favorite Harvey Dunn quote to carry around with you. I have mine but must confess the words may be slightly rearranged after nearly thirty years of use. “There are about ten thousand guys in this country that draw and paint better than I can,” Dunn said, “but they do not know how to make a picture and they never will.”

What does picture making mean to Harvey Dunn? Luckily, Walt Reed’s comprehensive monograph on Dunn contains a concrete example of this put into practice. The subject is a sailor rowing a dory who is lost at sea. Dunn reworked the picture after it was published because he was dissatisfied with the art direction. In clear before-and-after terms, Dunn shows us his method of complete immersion into a subject. He orchestrates the lighting, emphasizes the wilted spirit of the man, silhouettes him with the boat, and casts his future in doubt with a threatening sky. The fact that the figure and boat are reduced to simple shapes does not make them less recognizable. In fact, the opposite is true; both are now part of a greater theme. This could only come about because Dunn, the artist, had the confidence to lay off of the drawing. He was after bigger game, a higher purpose. He was after the spirit of the picture.

Although Dunn would hammer this theme over and over, his teaching had other points of emphasis, and at times, almost sounds like Emerson or Thoreau. There is Dunn the Philosopher, Dunn the Humanist, but closest to his heart was an empathy for the working artist. He observed that when an artist gets an idea and sits down to sketch it, all the doubts and second thoughts that had been hanging around in the corners sleeping come alive. He advised his students to carry on, noting that, “Ideas are intelligent active things which present themselves to your consciousness for expression. You can only be receptive and express them as they will be expressed.”

Dunn also bolstered his students’ spirits with advice that stressed they were not alone in their creative struggles. “We think of art as sort of a flimsy thing,” he said, “but do you realize that the only thing left from ancient times is the art… The Greek statues that are armless and nameless are just as beautiful today as they were the day the unknown sculptor laid down his hammer and chisel and said, ‘Oh, hell, I can’t do it!’”

About the Author

Dan Howe is a free-lance artist who has worked professionally since 1990. He attended the American Academy of Art in Chicago, and then traveled to New Mexico to study with the late illustrator and painter, Tom Lovell. He has taught at the American Academy, the University of Wisconsin, and the Scottsdale Artist School. His illustration clients include Marvin Windows and Doors, Binney and Smith, and Condé Nast, among others, and he has painted professional portraits for Oregon Health Sciences University, Southern Illinois Medical Center, San Francisco General Hospital, York Hospital, and University of Michigan. He currently lives in Connecticut with his wife and two daughters.

“Remembering America’s Golden Age”

SOUTH DAKOTA —In connection with The Norman Rockwell Museum, the South Dakota Art Museum is thrilled to have available a comprehensive exhibition featuring the art of Harvey Dunn (1884–1954). Dunn, a protege of legendary artist Howard Pyle, is renowned for his illustrations depicting the great plains of America’s Midwest, and his works were regularly reproduced in such magazines as Collier’s Weekly, Harper’s Magazine, The Saturday Evening Post, and Scribner’s.

Read the complete article on fineartconnoisseur.com…

“Harvey Dunn at the South Dakota Art Museum”

Artful Living Magazine, June 30, 2015

SOUTH DAKOTA —The Norman Rockwell Museum and the South Dakota Art Museum are honored to present the first major exhibition celebrating the art and legacy of American illustration master Harvey Dunn. A brilliant and prolific illustrator of America’s golden age, he was a prodigy of legendary artist Howard Pyle and an admired teacher in his own right.

|

Hunter Museum of American Art June 24, 2016 through September 25, 2016 Website: http://www.huntermuseum.org/ |