THE ART OF NORMAN ROCKWELL

THE ART OF NORMAN ROCKWELL | View Collection

American Magazines and the Power of Published Art | View Collection

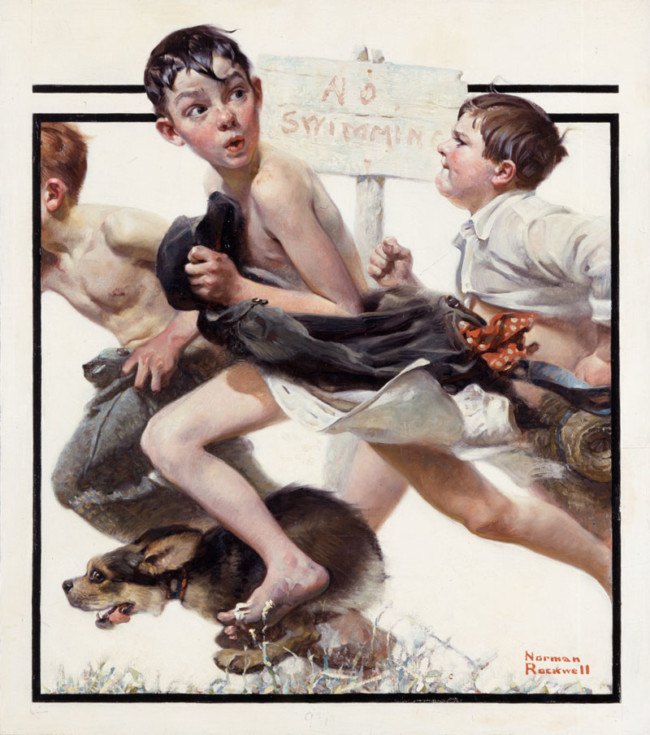

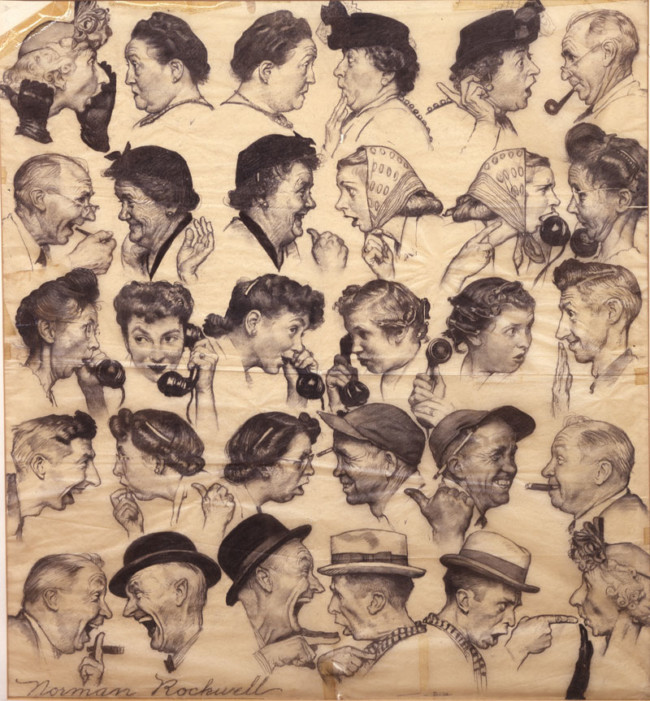

Humor and wit were central aspects of Norman Rockwell’s character. From his first Saturday Evening Post cover, Boy with Baby Carriage, in 1916 to his thematic No Swimming paintings to The Gossips, Rockwell filled a societal niche by providing levity during times of great strife. As Pablo Picasso noted, “the purpose of art is washing the dust of daily life off our souls.” Through two World Wars, the Great Depression, civil rights struggles, and the wars in Korea and Vietnam, Norman Rockwell’s paintings presented Americans with a window into a more idyllic world.

Though Rockwell is often regarded for paintings that addressed serious issues occurring at the moment of their creation, a great deal of Rockwell’s oeuvre is reflective of his sense of humor and natural playfulness.

World War II and the American Homefront | View Collection

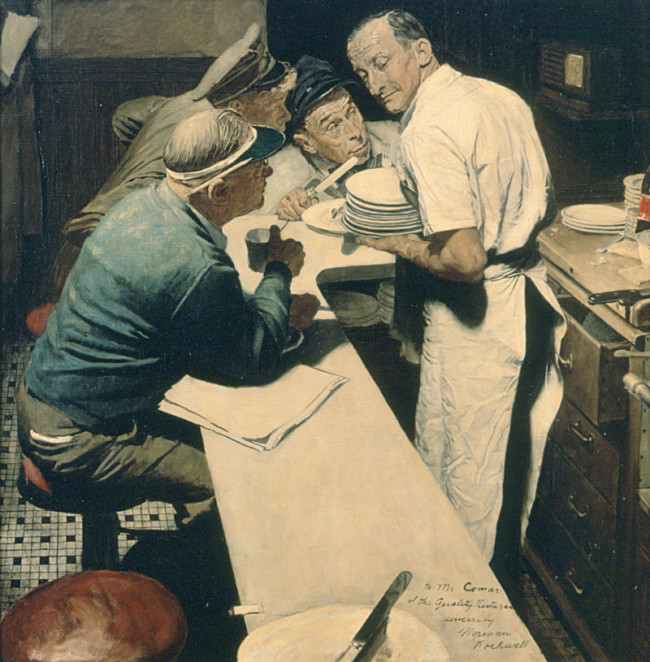

Distant from the activities of the war raging in Europe, Norman Rockwell was challenged to record his interpretation of the effects of World War II on servicemen, and on Americans at home. For Rockwell, an unassuming fictional private named Willie Gillis told the story of one man’s army in a series of eleven published (and one unpublished) Saturday Evening Post covers, in which he was depicted doing everything from proudly receiving a care package from home to peeling potatoes and reading the hometown news. Rockwell met his Willie Gillis model, Robert Otis “Bob” Buck, at an Arlington, Vermont square dance. Then fifteen years of age, Buck was exempt from the draft, but anxious to enlist, he eventually began his service in 1943 as a naval aviator in the South Seas. The name Willis Gillis was coined by Rockwell’s wife, Mary Barstow Rockwell, an avid reader who drew inspiration from the story of Wee Gillis, a 1938 book about an orphan boy by Munro Leaf. The first published painting in Rockwell’s Willie Gillis series, this lighthearted portrayal of hungry servicemen marching in step was clearly appreciated by Post readers, who inquired after Willie’s welfare and scrutinized the cover closely enough to observe that Rockwell had not actually placed sufficient postage on the package for sending. Enlargements of the Willie Gillis covers were distributed by the USO to be posted in USO clubs in the United States and overseas, and in railway-station and bus-terminal lounges.

Images of Childhood in the U.S.A. | View Collection

The term “Rockwellian” has been used to denote a world replete with harmony in familial relationships, patriotism, optimism, idealism, good-natured fun, and a general feeling that all is well. Adapting everyday situations by accenting and augmenting them to increase their visual and emotional punch, Norman Rockwell didn’t create a fantasy existence, but instead enhanced our own. Critics who have viewed his illustration work with contempt seem unaware that in Rockwell’s world children still disobeyed rules, adolescent girls grappled with social pressures, boys struggled with their evolution into manhood, and, in his most powerful paintings, society confronted issues of race.

Norman Rockwell possessed a distinct ability to create works of art that evoke a strong emotional response. Many of the emotions drawn from the viewer are memories of formative events from their own lives, nostalgia toward a time long gone, or a feeling of Americans collectively united through war-time patriotism. Whether rich or poor, young or old, educated or not, museum visitors often view Rockwell’s paintings with an emotional response or recollection. In certain works, the viewer’s reaction is minimal, noting only the composition or appeal of the characters and the situation of the subjects. In others, parents identify strongly with a mother supervising her children as they stir cake batter, fathers sympathizes with the dad wistfully watching as his daughter transitions to adulthood, children acknowledge scenes of youthful mischief, while others reminisce about their first childhood crush.

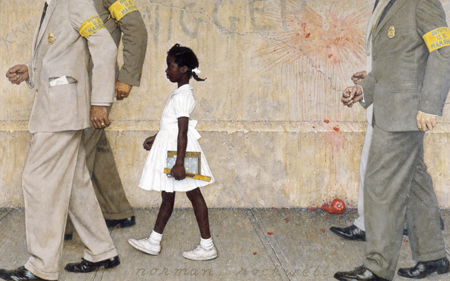

The American Civil Rights Movement | View Collection

Responsible for helping to shape the perception of American society and culture in the 20th century, Rockwell was at times a documentarian and a mythmaker. By transforming a blank canvas into a portrayal of a young African-American girl courageously enduring a hate-filled crowd on her walk to school, Rockwell depicted Ruby Bridges as a modern day Joan of Arc. Following his break with The Saturday Evening Post in 1963, Rockwell began to create paintings that allowed him to address more substantive matters.

Rockwell and Scouting | View Collection

Norman Rockwell’s long artistic relationship with the Boy Scouts of America began when the organization was still in its infancy. After successfully illustrating the Boy Scout Hikebook in the fall of 1912, Rockwell was retained for the permanent staff of Boys’ Life. The weekly magazine of the Boy Scouts of America had just expanded to national circulation. Six months later, Rockwell was promoted to art editor and he continued to work for Boys’ Life until 1917. In gratitude for this early break and the valuable experience he gained, Rockwell made a lifelong commitment to the Boy Scouts of America, producing their annual calendar illustrations from 1925 to 1976.

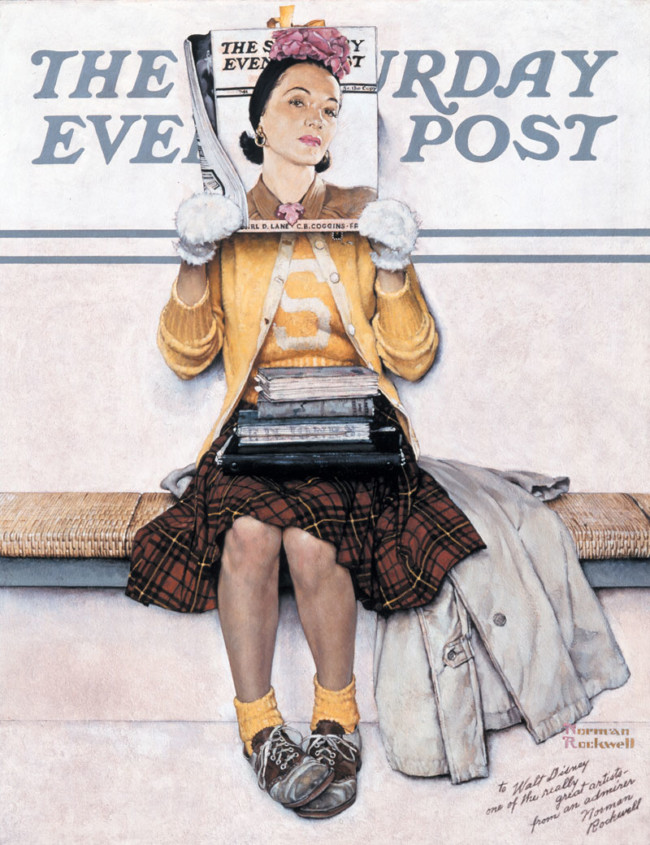

Covering The Saturday Evening Post | View Collection

Upon the urging of fellow illustrator and studio partner, Clyde Forsythe, Norman Rockwell walked into the Philadelphia headquarters of The Saturday Evening Post in early 1916 with two paintings he hoped to have published on the cover of the most widely read publication in the United States. Editor George Horace Lorimer was so impressed that he immediately agreed to purchase the works for future publication.

Rockwell noted, “In those days the cover of the Post was the greatest show window in America for an illustrator. If you did a cover for the Post you had arrived. . . . Two million subscribers and then their wives, sons, daughters, aunts, uncles, friends. Wow! All looking at my cover.” From his first cover in 1916 to his final illustration in 1963, the Post published 321 covers of original Rockwell paintings.

Norman Rockwell’s Advertisements | View Collection

Though best-known for the 323 Saturday Evening Post covers depicting his paintings, Norman Rockwell was consistently in high demand from companies wishing to capitalize on his beloved images of everyday Americans. Beginning with a commercial illustration for Heinz in the 1914 edition of the “Boy Scout Handbook” to his final commissioned artwork for Lancaster Brand Turkeys in 1976, Rockwell assisted several dozen companies in improving their brand and increasing their sales.

Some of Rockwell’s clients included Fisk Tires, Interwoven Socks, Edison Mazda, Elgin Watches, Jell-O, Parker Pen, Campbell’s Tomato Juice, Arrow Shirts, Listerine, Mass Mutual, Skippy Peanut Butter, Crest, Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, Plymouth, Ford, General Motors, Mobil, Coca-Cola, and Pepsi, in addition to work for the United States Office of War Information during World War II. His longest-held client was the Boy Scouts of America, for whom he illustrated their annual calendar for over 50 years.

Continuing to show the strength of Rockwell’s influence on American culture, during Thanksgiving 2015 Butterball reproduced Rockwell’s Freedom From Want painting on packaging for its turkeys.

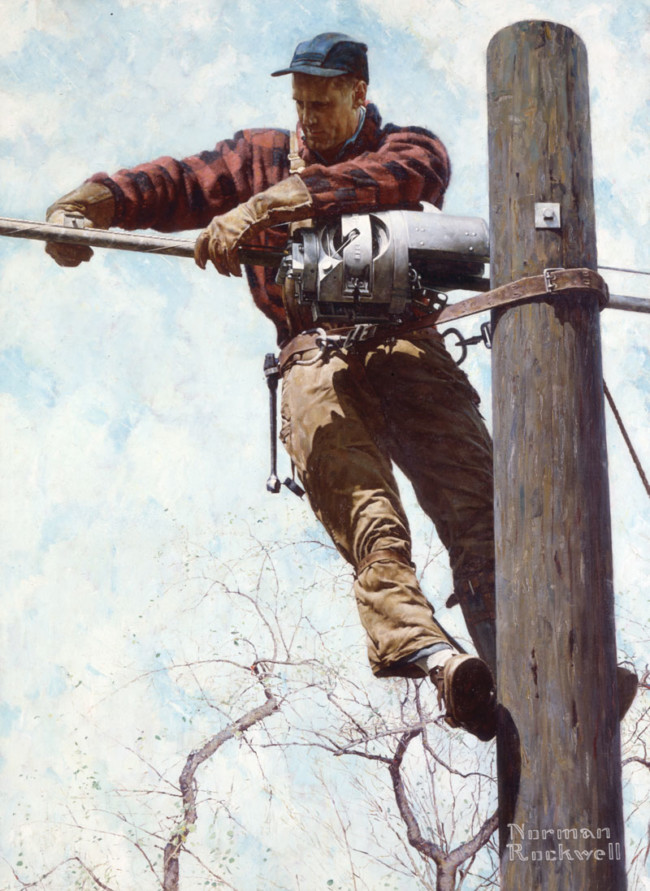

Norman Rockwell’s Artistic Process | View Sample Collection

A natural storyteller, Norman Rockwell envisioned his scenarios down to the smallest detail, yet at the easel he found it difficult to paint purely from his imagination. In his first decades as an illustrator, he could not paint without studio models in continual view as he worked, explaining that it had “never been natural” for him to “deviate from the facts” of the subject before him.

Rockwell turned to photography as an efficient, accurate, and liberating means to satisfy his literalism. By photographing his props wherever he found them he no longer had to assemble together the disparate objects his narratives required. By photographing far-flung settings he was able to introduce true-to-life backgrounds. And by freeing him from the drawbacks of live models, photography dramatically expanded his vocabulary of available postures and possible expressions. “Now anybody could pose for me,” Rockwell said, and he took full advantage of the opportunity. Rockwell’s trademark animated faces became possible because they could first be captured on film.